L.A. dramatically increases ‘water cops’ staffing as drought worsens

Los Angeles officials announced Monday they are beefing up their water-wasting patrols. But just don’t call them “water cops.”

Until now, the Department of Water and Power has assigned just one inspector to drive around handling complaints of water wasting in a city of 4 million people.

The DWP said Monday it now has four water-wasting inspectors, but officials emphasized that their job will be more educational than enforcement. From January through June, the unit received 1,400 reports of violations and handed out 863 warnings letters. But so far, no one has been fined.

This tracks with the approach of many California cities, which have found it more effective to warn residents about using too much water than to ticket them.

New state rules allow fines as much as $500 to water wasters, and local authorities, including the DWP, have adopted such penalties. But Max Gomberg, the State Water Resources Control Board senior environmental scientist, has said relatively few fines have been handed out.

For example, Santa Cruz has established a “Water School” modeled after traffic school, allowing those caught using too much water to work off their fine by attending class. Sacramento has deployed extra staff to patrol the streets, but officials hope that warnings will do the trick.

“Usually, just getting a notice is going to take care of whatever the issue is,” Gomberg said. “The citiations are reserved for either people who are oblivious or simply refuse to help out.”

L.A.’s experience bears that out, officials said. The DWP used a “drought buster” team to look for water wasters from 2009 to 2012. During that period, the DWP got about 30,000 reports of violations, spokeswoman Michelle Vargas said. About 9,000 people were issued warnings. But only about 300 were assessed fines when they were found to have wasted water again, Vargas said. And of those 300, none ended up becoming a repeat offender after being fined, she added.

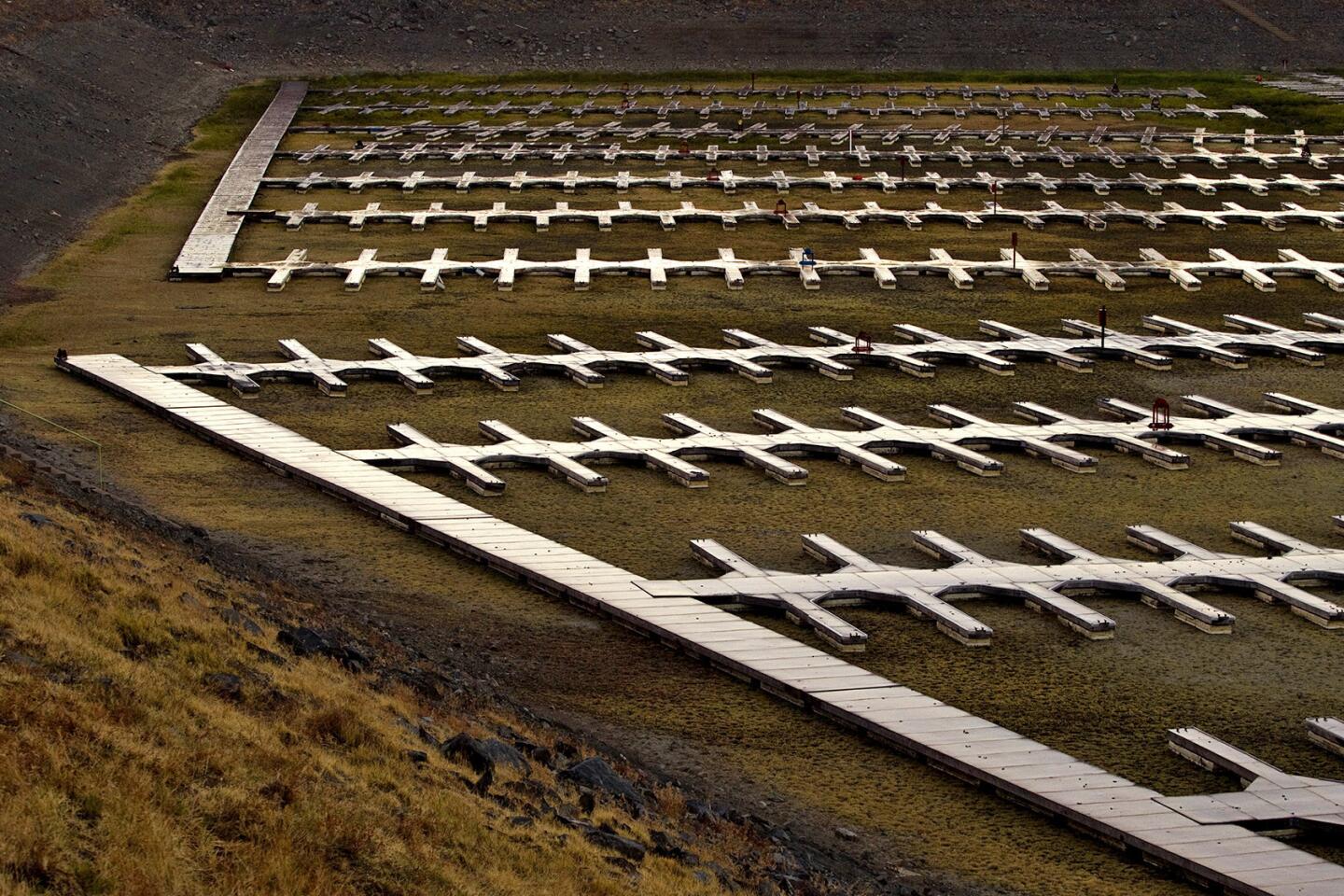

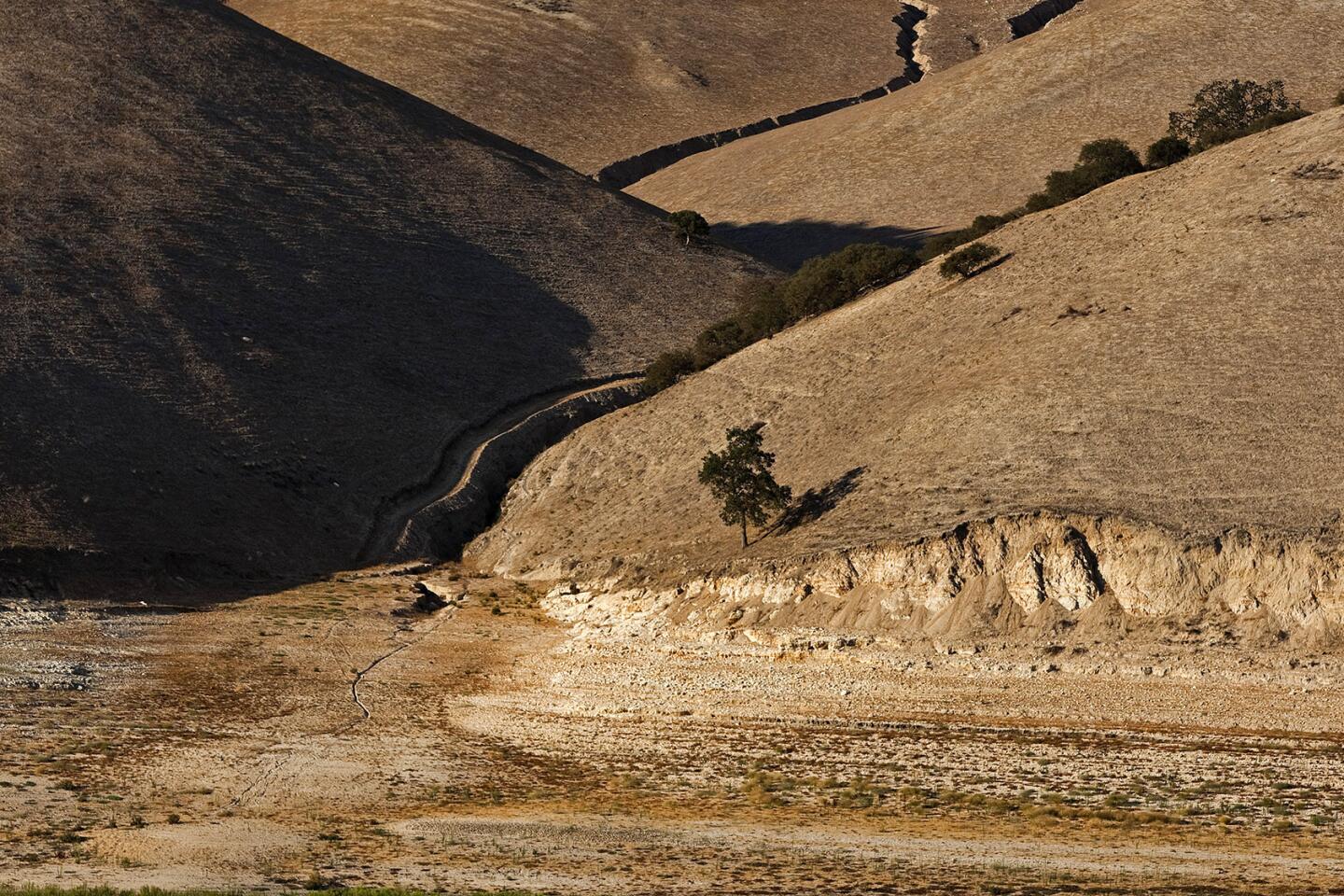

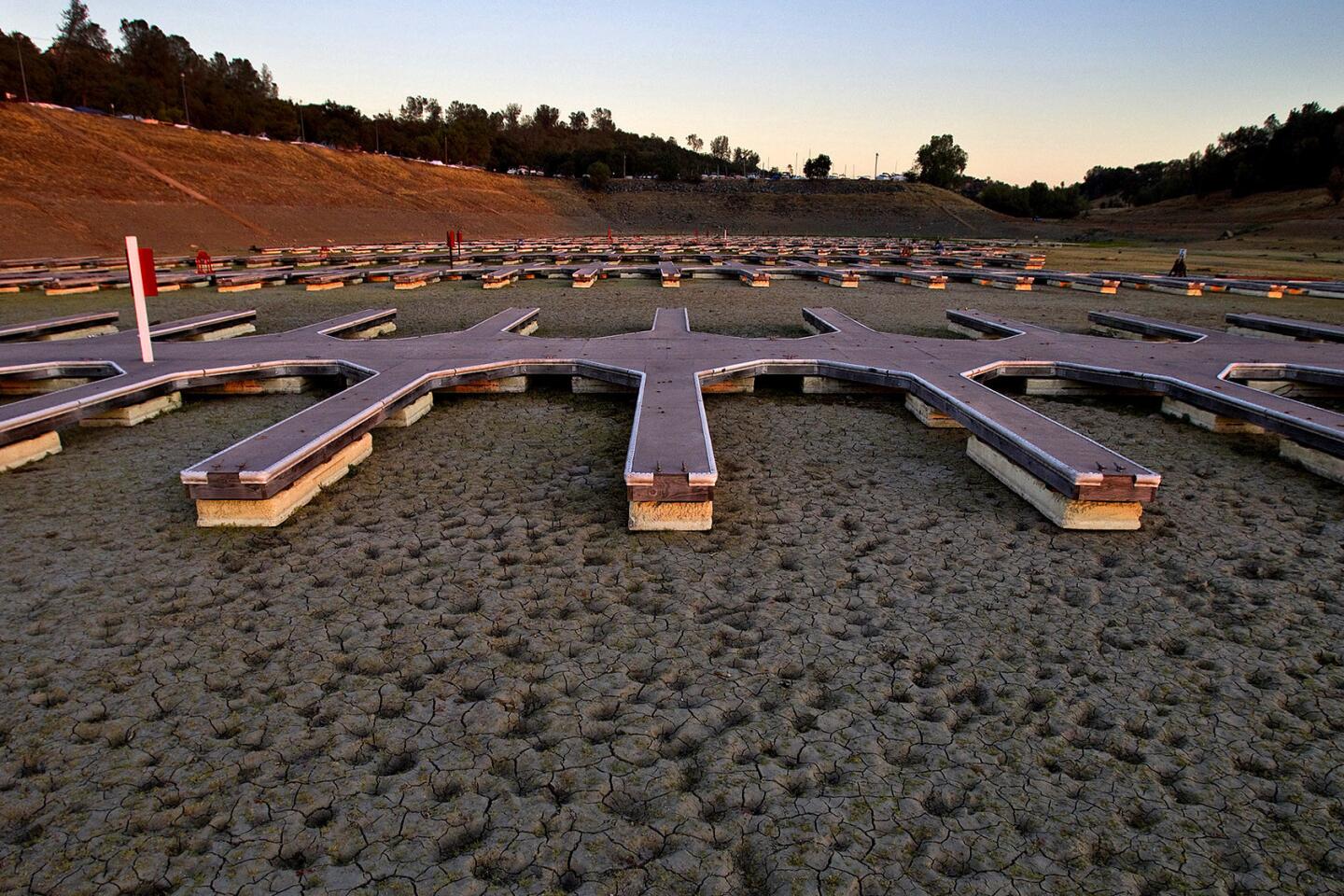

But the DWP warns that this friendly approach will change if the fall doesn’t bring rains.

L.A. is in Phase 2 of a mandatory water-conservation ordinance. Among other restrictions, that means watering no more than three times a week and never on Saturdays and not being able to wash a car unless one uses a “self-closing water shutoff nozzle.”

A dry winter would kick in Phase 3, which would prohibit washing cars unless it’s at a commercial carwash and watering one’s lawn only once a week.

In L.A., failure to abide by the rules after getting a warning could result in fines of as much as $300 for residential customers and $600 for commercial customers.

“We won’t be so friendly and just educational any more,” said Rick Silva, who had been the DWP’s lone inspector.

Silva said among the most common violations are irrigating on the wrong days and water runoff, in which a lawn is irrigated so much that water ends up running into the street.

There is greater focus on outdoor water waste partly because technological advances, such as low-flow toilets, have made water use inside of buildings more efficient.

What the DWP has been trying to do so far, Silva said, is to educate people so that they change their water-usage habits — something that the city points out has already been happening. L.A. uses the same amount of water it did decades ago, Vargas said.

Stephanie Pincetl, director of UCLA’s California Center for Sustainable Communities, said studies have found that mandatory water restrictions are more effective at reducing water usage than voluntary restrictions.

Still, she said simply adding so-called “water police” may help “reduce water usage again, but that’s not a long-term change.”

What’s needed, Pincetl said, is a longer-lasting change in the water-use culture.

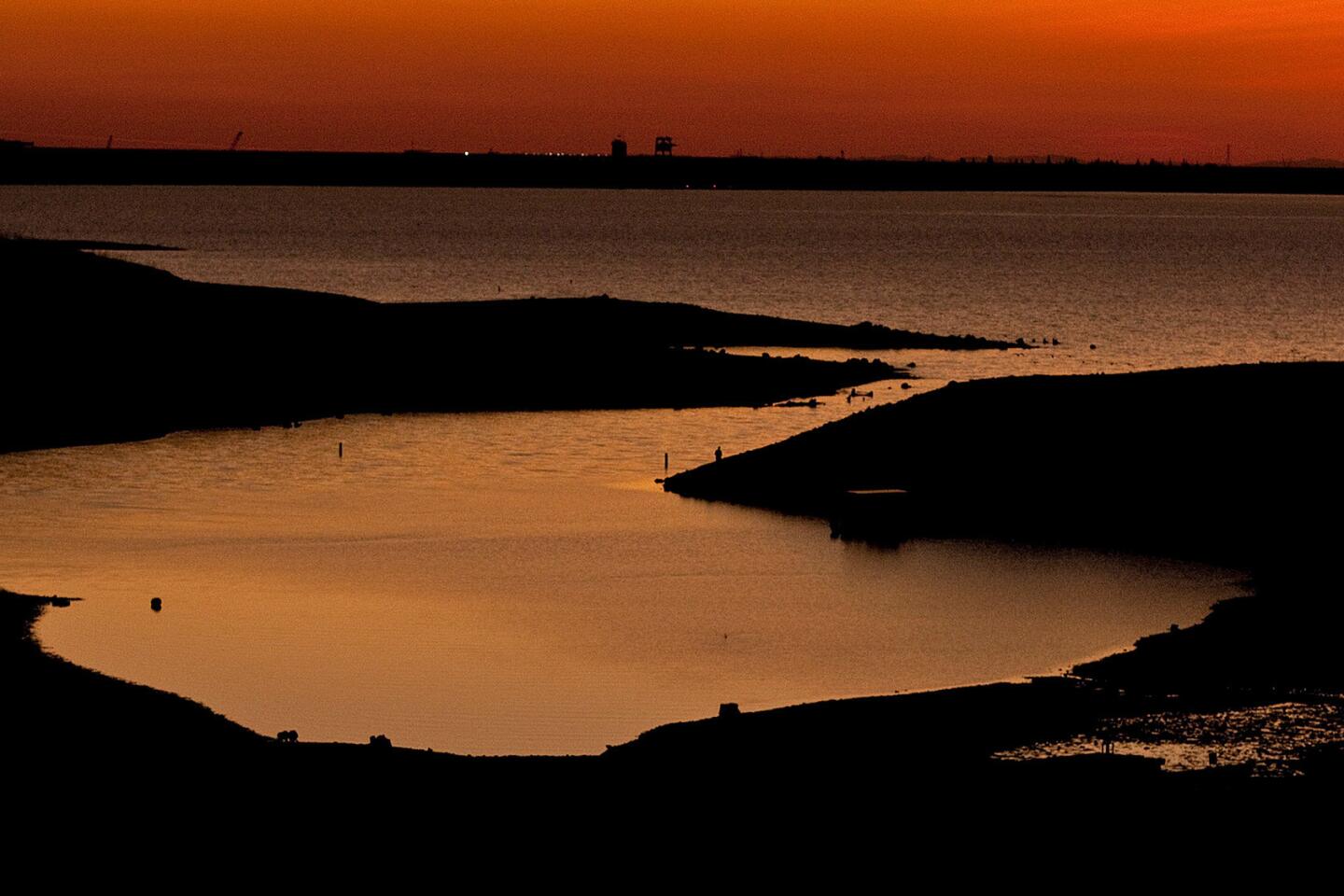

This drought “is not a temporary state for the state of California. This is something we’ve experienced before,” she said. “This happens to be the worst in 100 years, but it’s not something that’s unique. How do we respond over time so that we’re not in this crisis, reactive mode?”

Last month, state regulators found that there was an 8% increase in water use in Southern California. The precise number was quickly disputed, with water agencies such as Santa Ana asserting that their water use had not increased anywhere near the state’s numbers.

The DWP had a 9% increase in May compared with the average of the three previous Mays. But it touted a dramatic decrease over the long term, with L.A. using the same amount of water now as it did 40 years ago, despite having a much larger population.

But with a worsening drought, no one disputes that more has to be done. In the meantime, water officials have gotten some help from social media.

A #droughtshaming hashtag on Twitter allows people to out strangers if a sprinkler is raining water onto a sidewalk or a pipe leak is spewing water into a gutter. The viral ice bucket challenge — in which people get doused with buckets of ice water on video to raise awareness for ALS – have been high-profile targets of the Twitter campaign.

Then there was the spectacular rupture of a DWP pipeline that spilled 20 million gallons of water and flooded parts of UCLA and Westwood on live TV. Even though the DWP has a leak rate half the national average, according to Vargas, the utility was criticized for that in light of its push for Angelenos to conserve.

“We did get phone calls and emails,” Silva said. “They wanted to know if the DWP would get fined.”

hector.becerra@latimes.com

matt.stevens@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.