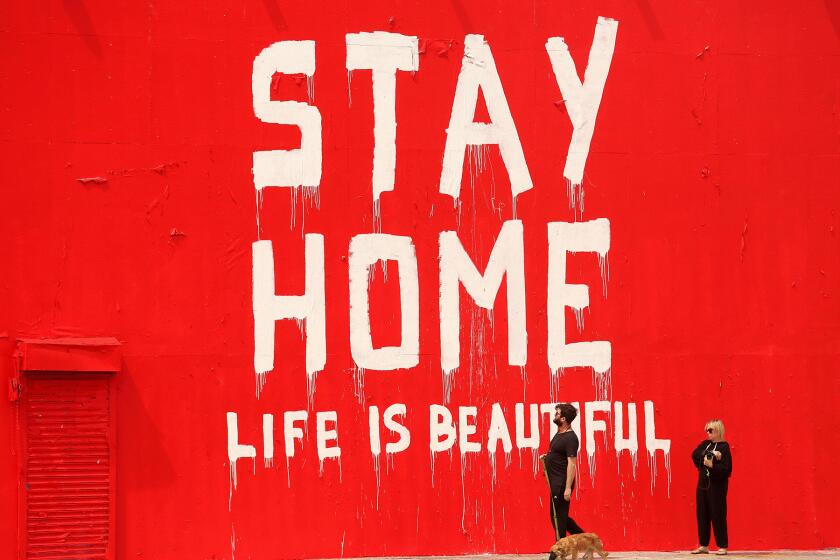

Many aren’t buying public officials’ ‘stay-at-home’ message. Experts say there’s a better way

With the coronavirus running rampant in Los Angeles and hospitals projected to overflow by Christmas, officials have fallen back on a familiar refrain: Stay home.

“My message couldn’t be simpler: It’s time to hunker down. It’s time to cancel everything,” Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti said last week. “If you’re able to stay home, stay home.”

Some 33 million Californians are now under a new regional stay-at-home order that began Sunday night, a last-ditch effort to turn the corner on an alarming rise in coronavirus cases statewide. The blunt messaging worked to bend the curve in the spring, when fear of the novel virus and the insidious ways it might spread kept many indoors. But nine months later, the words seem to have lost their meaning.

The percentage of Angelenos staying home except for essential activities has remained unchanged since mid-June — around 55% — despite pleas from health officials in recent weeks for people to cut down on their activities, according to a survey conducted by USC.

A similar story has played out nationwide, as millions of Americans zigzagged across the country to visit family over the Thanksgiving holiday, flouting the advice of health officials.

“It’s not because the public is irresponsible; it’s because they are losing trust in public health officials who put out arbitrary restrictions,” said Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious-disease specialist at UC San Francisco. “We are failing in our public health messaging.”

What’s the reasoning behind Los Angeles County’s new restrictions designed to stop the coronavirus from spreading? We assess the science behind each one.

Health officials are up against a fatigued public, as well as a number of people who don’t believe in the danger of the virus, Gandhi said. But she is also part of a growing number of experts who think there’s a better way to engage those who do want to take the pandemic seriously — by taking a lesson from the public health strategy known as harm reduction.

Typically used to describe sex-education programs and needle exchanges for drug users, harm reduction aims to mitigate the risks of dangerous behaviors instead of trying to get people to cease altogether.

When it comes to the COVID-19 pandemic, a harm-reduction approach would encourage masking and social distancing instead of demanding that people have no contact at all with friends or family they don’t live with. In other words, even during a pandemic, abstinence-only isn’t effective.

L.A., however, has adopted more of a “just say no” attitude. Last week the county became one of the only places in the nation to halt all outdoor gatherings among people who aren’t in the same household, prohibiting two friends from meeting up in a park or going on a hike with masks on. Gov. Gavin Newsom followed suit and included the ban in his regional stay-at-home order.

As a new stay-at-home order came for much of California, daily new coronavirus cases in Los Angeles County are increasing at an even faster pace than officials had forecast earlier in the week.

California officials are desperate to reverse an unprecedented flood of new coronavirus cases up and down the state, and even their critics acknowledge the impossibility of the situation. But banning relatively safe outdoor activities risks alienating people who want to follow the rules but feel exhausted, disregarded and sometimes confused by them, Brown University health economist Emily Oster said.

“Some of the things they’re telling you not to do are incredibly low-risk,” Oster said. “When you are so strict about what people can do, they stop listening.”

Aggressive shutdowns and widespread closures of businesses can persuade people to stay home and ultimately turn the tide on a major surge, as has happened in other parts of the world, experts say. And it is possible that the increasingly urgent pleas of officials in recent days may indeed push large numbers of people to start staying home again.

But in L.A. County, the latest measures have already sparked unprecedented backlash, particularly because of what many see as inconsistent policies. Unlike successful lockdowns in other countries that keep people inside by closing almost all businesses, officials here are reluctant to close shops without federal aid to ease financial losses.

For many parents confounded by an array of official dictates, closing playgrounds crossed a line in the sandbox.

So in L.A.’s current version of a shutdown, people are asked to shelter in place while big-box stores and malls welcome customers for holiday shopping.

“It says it’s not safe to even leave your house, stay home as much as you can, but I’m forced to go to work,” said L.A. retail employee Toby Thomas, who has an autoimmune condition that makes her especially vulnerable to COVID-19. “They’re just contradicting themselves with everything that they say.”

The concept of harm reduction originally came into use in the 1980s when doctors and activists struggled to reduce HIV transmission among people injecting drugs. Instead of stopping them from using drugs altogether, they opted to provide clean needles that would at least make the behavior safer.

The philosophy now applies to any public health issue for which mitigating risk has been found to be more effective than an all-or-nothing approach, including providing condoms to teenagers to promote safer sex or slowly weaning patients off junk food to improve their diet, said Dr. Eric Kutscher, an internal medicine physician at New York University.

Photos look back at 2020’s wild ride in the Golden State.

Kutscher, who recently wrote about harm reduction and COVID-19, said it acknowledges an uncomfortable truth: that people are going to socialize whether they are allowed to or not.

He added that he thinks health officials’ rhetoric lacks nuance in part because they were initially trying to drown out President Trump’s downplaying the threat of the virus. But as a front-line physician, Kutscher fears that the current messaging shames people and doesn’t consider their needs — that they may still have to go into work, that they may be lonely and depressed.

“Clearly what we’re doing is not working,” Kutscher said. “The idea of people gathering on Thanksgiving, it’s terrifying. It really upsets me, but I think we need to figure out how to get beyond that visceral response to instead focus on an actual productive conversation.”

A pandemic response guided by harm reduction would explain the risk levels of different activities and let people decide their comfort levels, with perhaps the most dangerous settings prohibited altogether. Public health research has found that this strategy makes people feel empowered to make their own choices and that, ultimately, they don’t take more risks than they would have otherwise.

By Tuesday, the stay-at-home orders will be in effect in 28 counties encompassing 84% of California’s population

Following the harm-reduction model, New York City’s health department has released guidance that helps people navigate both socializing with friends as well as sexual encounters during the pandemic. In San Francisco and other parts of the Bay Area, officials acknowledged that socializing can boost mental health and provided advice on creating social bubbles and safely sharing a meal outdoors with friends.

But not in Los Angeles. Here, outdoor gatherings of any kind were not officially permitted until mid-October, so any Angelenos seeing friends before that were left to determine their own precautions. And now, as part of a three-week emergency order that also closed playgrounds and outdoor dining, such meet-ups are prohibited again.

“It just seems like a slap in the face,” said Kate Stanwick, 32.

After several lonely months of staying home, Stanwick began going on masked, distanced jogs with a friend in the mornings, which she feels remains a low-risk option despite the latest crackdown. “It forces me into a position where I am breaking the rules,” she said.

None of the five designated regions in California have reached the critical under-15% ICU capacity, but all are expected to hit that mark soon.

L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said that with such high prevalence of COVID-19 throughout the county, even outdoor gatherings can become unsafe if people spend a long time together, especially if they don’t keep their masks on. The new measures are an attempt to quickly drive down case rates to prevent hospitals from overflowing, she said.

“We don’t really have any choice but to use all tools on hand to stop the surge,” Ferrer said. “This is not forever.”

When asked why the county does not try borrowing some principles of harm reduction, Ferrer said that attempts to give more control to people and businesses have failed in L.A. County. It only works if people keep their masks on and properly distance, and that isn’t happening, she said.

If people “are fatigued and don’t really want to continue to take these basic precautionary steps, then this approach doesn’t work as well as it ought to,” she said. If even a small fraction of people don’t comply with the safety measures, that can still lead to thousands of cases and even deaths, she said.

COVID-19 is ‘greatest threat to life in Los Angeles that we have ever faced,’ Garcetti says

Still, banning small outdoor hangouts does little to stem the spread of the virus and could backfire, said Julia Marcus, an infectious-disease researcher at Harvard University. Most coronavirus transmission occurs indoors, especially in poorly ventilated environments, studies have found.

“Outdoor gatherings that are masked and distanced — that is a place where we can give people a break so they can avoid the situations we really want them to avoid, like crowds and indoor dinner parties,” Marcus said. “The thing that can save L.A. right now is getting people outdoors, and instead there are these policies that may actually do the opposite.”

Rabi Abonour, 30, enjoyed masked bike rides with friends to break up the monotony of living alone during the pandemic. But he feels let down by the latest policies, which seem unnecessarily punitive and not aligned with the available science, he said.

“The numbers continue to rise,” he said. “It’s like, ‘Is this really working?’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.