1968: Lakers’ first ‘Big 3’ didn’t deliver immediate banner

Parades were planned. Postgame speeches had been choreographed. Champagne would be chilled, opened and poured. And balloons would float from the sky when the inevitable happened.

The Lakers were going to slay the NBA’s unstoppable dragons — Bill Russell and the Boston Celtics. Lakers owner Jack Kent Cooke was sure of it. His players were sure of it. The city was sure of it.

How could they not be?

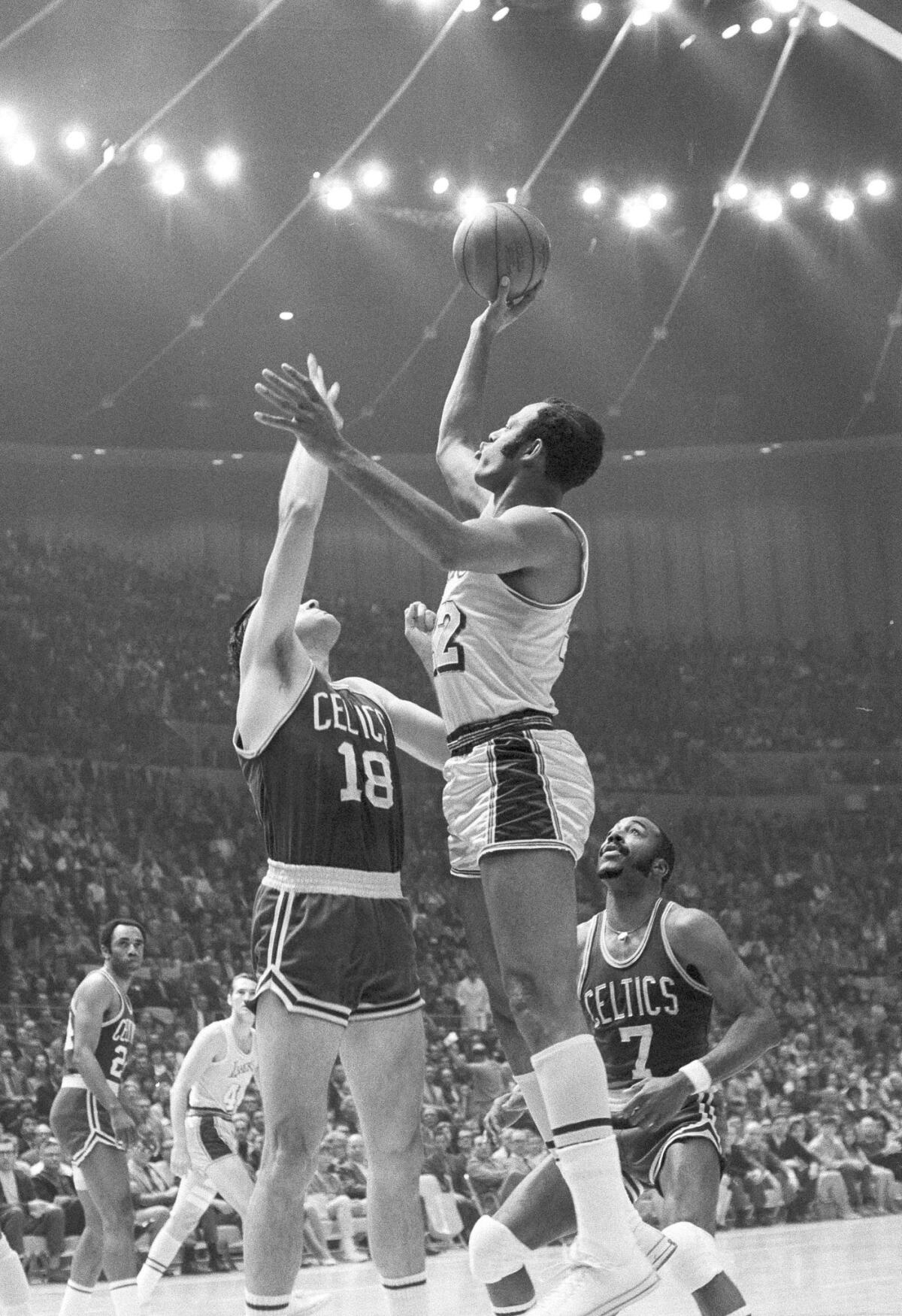

Their destiny was assured on July 9, 1968, when the Lakers traded for Wilt Chamberlain, the reigning MVP of the league.

Titles were sure to follow. This was Mr. 100 points in a game, an unstoppable force on offense joining two other all-time greats — Elgin Baylor and Jerry West. No team would be more talented. No team would have more firepower.

The deal created only the best kinds of concerns about the upcoming season.

Were there too many stars? Did the Lakers have too much talent? Would there be anyone good enough to force the Lakers to work hard for the championship sure to come?

But months later, after a Game 7 in Inglewood that marked the final day of that season, Red Auerbach, Boston’s general manager and legendary former coach, stalked the Celtics’ locker room at the Forum with another question on his mind:

“What are they gonna do with all those … balloons now?” he shouted.

::

Fifty years after the Lakers sent Jerry Chambers, Darrall Imhoff and Archie Clark to the Philadelphia 76ers for Chamberlain, the organization again struck gold in the offseason.

LeBron James signed as a free agent. Only his arrival, unlike Chamberlain’s, wasn’t met with immediate expectations for a championship.

Some of that has to do with the Lakers’ current roster and some of it has to do with their division rival, the Golden State Warriors, who seem to have the NBA in a sleeper hold.

In the near future, James is expected to attract another wave of stars to come to Los Angeles to help the Lakers try to break the Warriors’ grasp on the league — a fight the Celtics, 76ers, Houston Rockets, Oklahoma City Thunder and others are also waging.

“Dynasties are nothing new in this league,” NBA Commissioner Adam Silver said recently in Las Vegas. “There is a long history of it.”

The ’60s, maybe more than any other decade in the 20th century, showed how tough it could be to keep the best teams from getting to the top and staying there.

In 1964, the Yankees made their 15th appearance in the World Series in 18 seasons, winning nine of them. The Green Bay Packers might as well have been wearing green-and-gold pinstripes on the football field, as they dominated the game by winning three NFL championships and two Super Bowls between 1961 and 1967. The Montreal Canadiens appeared in five consecutive Stanley Cup Finals in the ’60s, winning four of them. And in Los Angeles, the UCLA Bruins began a 12-year run in which they won the NCAA men’s basketball tournament 10 times.

But those dynasties were nothing compared to what was happening in the NBA, where the Celtics were running an entire empire.

::

It began with a trade.

Boston sent two future Hall of Fame players to St. Louis for the No. 2 pick in the draft, Russell — a deal which, in hindsight, was comically lopsided. Five Hall of Famers might not have been enough for the player that rookie was to become.

With Russell on board, Boston went on a run unequaled in professional basketball: 11 titles in 13 seasons, including a stretch of eight in a row.

“Russell was such a dominant player himself, plus he was playing with a great team,” Baylor recalled this week. “The Celtics were a very good team; they had players who really complemented one another and they had been around a while. They played like it.”

If you were going to beat Boston — the Lakers had already failed six times during the Celtics’ run — you needed someone who could neutralize Russell.

Following a six-game loss in the 1968 NBA Finals, the Lakers emerged as a possible landing spot for Chamberlain. That he would stay in Philadelphia seemed unlikely, especially with him grumbling about wanting to pick the team’s next coach, or even do it himself.

A new basketball league, the ABA, had their heart set on him, wanting to bring him to Los Angeles to play for the Stars. Some people say the team even had a handshake deal with Chamberlain to make it happen.

On July 5, a Friday, the Associated Press reported that a deal sending Chamberlain to the Lakers would be made. However, league Commissioner Walter Kennedy and Chamberlain both denied it.

“There will be no announcement Monday or Tuesday concerning me unless it is the fact I will be in New York those days, helping Mr. [Richard M.] Nixon with his campaign,” Chamberlain told the Los Angeles Times.

By Monday night, though, the trade was official. “Chamberlain coming to L.A.,” the headline read.

“Most of the teams that have won have had a dominant center. It’s something you pretty much need,” Baylor said 50 years later. “I thought at least we had a shot. With Wilt, we’d have a shot.”

Chamberlain, who died in 1999, was even more confident.

“With guys like Jerry West and Elgin Baylor, I feel very happy in being traded to a team that may stand a chance to go down in the records as one of the best teams in basketball ever,” he said.

Times columnist Jim Murray wrote. “We got Goliath. … For years, basketball seers have agreed on one thing: If the Lakers ever got a good big man in the pivot, it would be all over.”

But it wasn’t. Not for a while.

“People’s perception was we’re going to win it right away,” former Lakers forward Mel Counts said. “And of course, that didn’t happen. You had three Hall of Famers, three of the best, and you have instant success. That’s not the case.

“It didn’t pan out that way.”

::

The 1968-69 season got off to a slow start, the Lakers losing three of their first four games before getting on track. And even when they started winning, they were still adjusting.

Baylor, who loved to drive the ball to the basket, wasn’t used to having a center like Chamberlain clogging up the paint.

But Chamberlain, in something of a surprise, deferred to West and Baylor when it came to scoring. In his first season with the Lakers, Chamberlain took an average of 13.6 shots per game — about a third of what he tried at his shot-taking peak.

“You get to a stage in your life and your ultimate goal is to win a championship. And if you have to do that to win, that’s fine,” Counts said of Chamberlain. “Then you’re considered a winner, not only individually talented.”

The Lakers found their gear and cruised to 55 wins, most in franchise history to that point. And after a pair of clunkers against the Warriors to open the playoffs, the Lakers won eight of their next nine games to get to the Finals.

There was just one tall, rangy problem standing between them and a championship: “I knew that with Bill Russell, it was going to be very difficult,” Baylor said.

The 1968-69 season was the last the Lakers would see Russell, and what he did during a seven-game series in the Finals cemented how happy they’d be when he retired at its conclusion. Russell dominated Chamberlain, holding him to averages of 11.7 points and 3.0 assists in the series, and the Lakers center missed an important chunk of the decisive game with an injury. However, Chamberlain did average 25 rebounds in the series.

West was terrific, winning the Finals MVP in the losing cause, but the Lakers’ first super team ended the season without a title.

“Of course it’s disappointing,” Counts said. “…There’s no better feeling than being on a championship team.”

The Lakers eventually got there; it just took longer than most people anticipated. The next season, they lost in seven games to the New York Knicks.

Before the 1970-71 season, Counts was sent to Phoenix for Gail Goodrich, returning the future Hall of Famer to the Lakers after the Suns swiped him in the 1968 expansion draft. But injuries derailed that campaign.

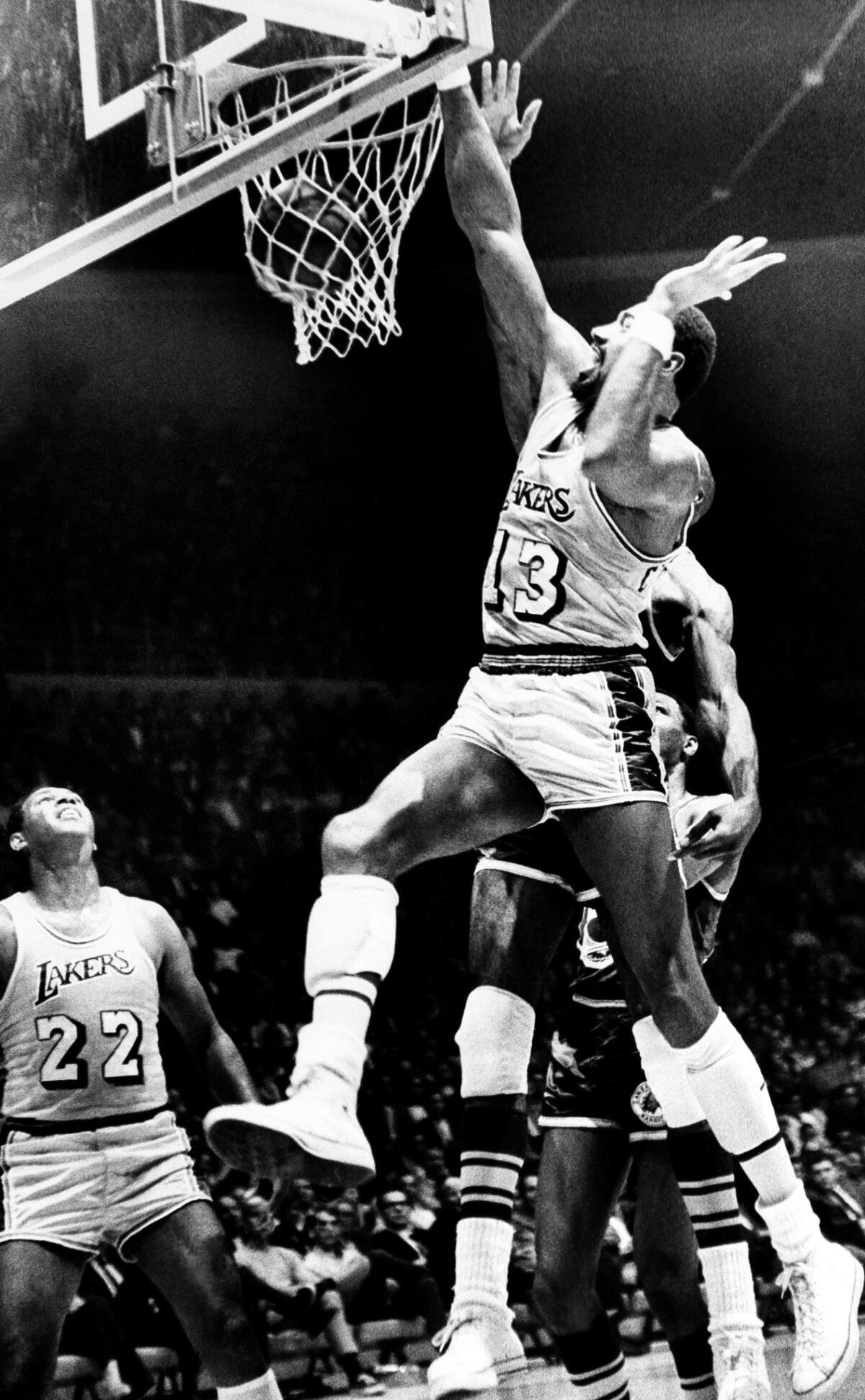

It wasn’t until 1971-72 that the Lakers reached the potential Chamberlain foresaw, winning a then-record 69 games, including a still-record 33 consecutive games.

Baylor, who had aching knees, retired just nine games into that season, missing the glory of the team’s first NBA title in Los Angeles.

Chamberlain had 24 points and 29 rebounds in the Game 5 series clincher over the Knicks.

Instead of the “Big 3” delivering a championship, it was West and Chamberlain, along with Goodrich, Jim McMillian and Happy Hairston.

::

The Lakers and their newest superstar, James, won’t be burdened by the expectations placed on Chamberlain, West and Baylor in 1968.

One-year deals recently given to Rajon Rondo, Kentavious Caldwell-Pope, Lance Stephenson and JaVale McGee signal that the Lakers have something big planned next summer — perhaps the addition of another all-star or two to team with James.

If that happens, things will feel different. But the lessons from 1968 should offer a warning. Dynasties are difficult to scuttle, especially quickly.

“It took some time to get the missing pieces,” Counts recalled.

In James, the Lakers already have Goliath. With another star or two, they may be tempted to plan parades, chill champagne, even hoist balloons to the ceiling.

Maybe this time they’ll fall.

Twitter: @DanWoikeSports

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.