Authorities received repeated warnings in months before three young siblings were killed

In the months before three young siblings were slain inside a Reseda apartment, the alarms about Liliana Carrillo’s ability to care for the kids grew louder and louder.

Carrillo was “extremely paranoid” and erratic, according to her boyfriend’s account in court papers, which described her increasingly bizarre claims: that she was “solely responsible” for the COVID-19 pandemic and that his hometown of Porterville was beset by a pedophile ring.

“I am afraid for my children’s physical and mental well-being,” the kids’ father, Erik Denton, told a Tulare County judge last month before he was granted physical custody.

The warnings reached officials in Los Angeles County as well. The county’s child welfare agency and the Los Angeles Police Department were alerted, on numerous occasions, that Carrillo was a danger to the young children, according to interviews by The Times with Denton and his family along with court records and sources familiar with the ongoing investigation.

L.A. County’s Department of Children and Family Services had received at least two separate reports involving the family. But despite repeated conversations with the children’s father and family and a court order from a Tulare County judge that restricted the mother’s custody, social workers opted to keep the children with their mother, according to records and interviews.

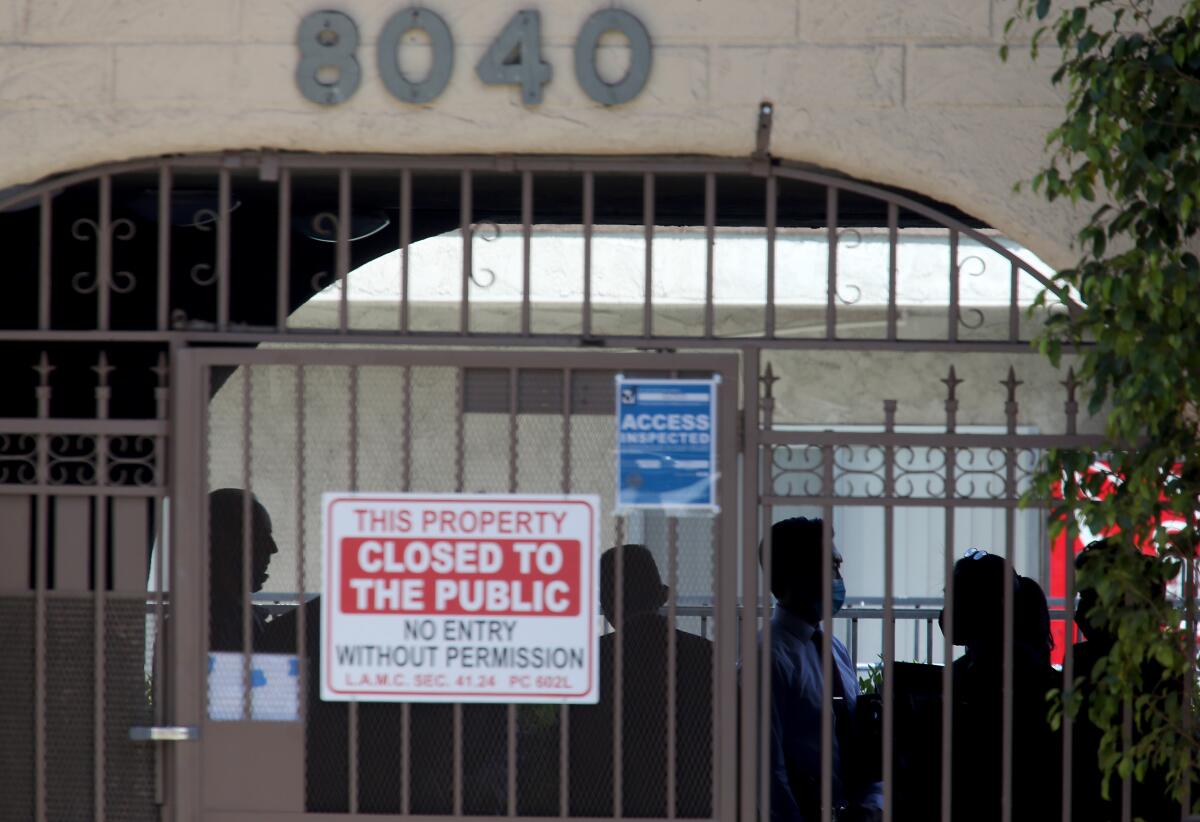

Neighbors stunned by killing of three ‘beautiful’ young children in Reseda.

“We kept bringing up all the right red flags about her behavior,” said Dr. Teri Miller, an emergency room physician in L.A. who is also a cousin of Denton’s and assisted in a weeks-long effort to get the children to safety. “The judge in Porterville listened and read all the information, but everyone in L.A. kept pushing it off on someone else.”

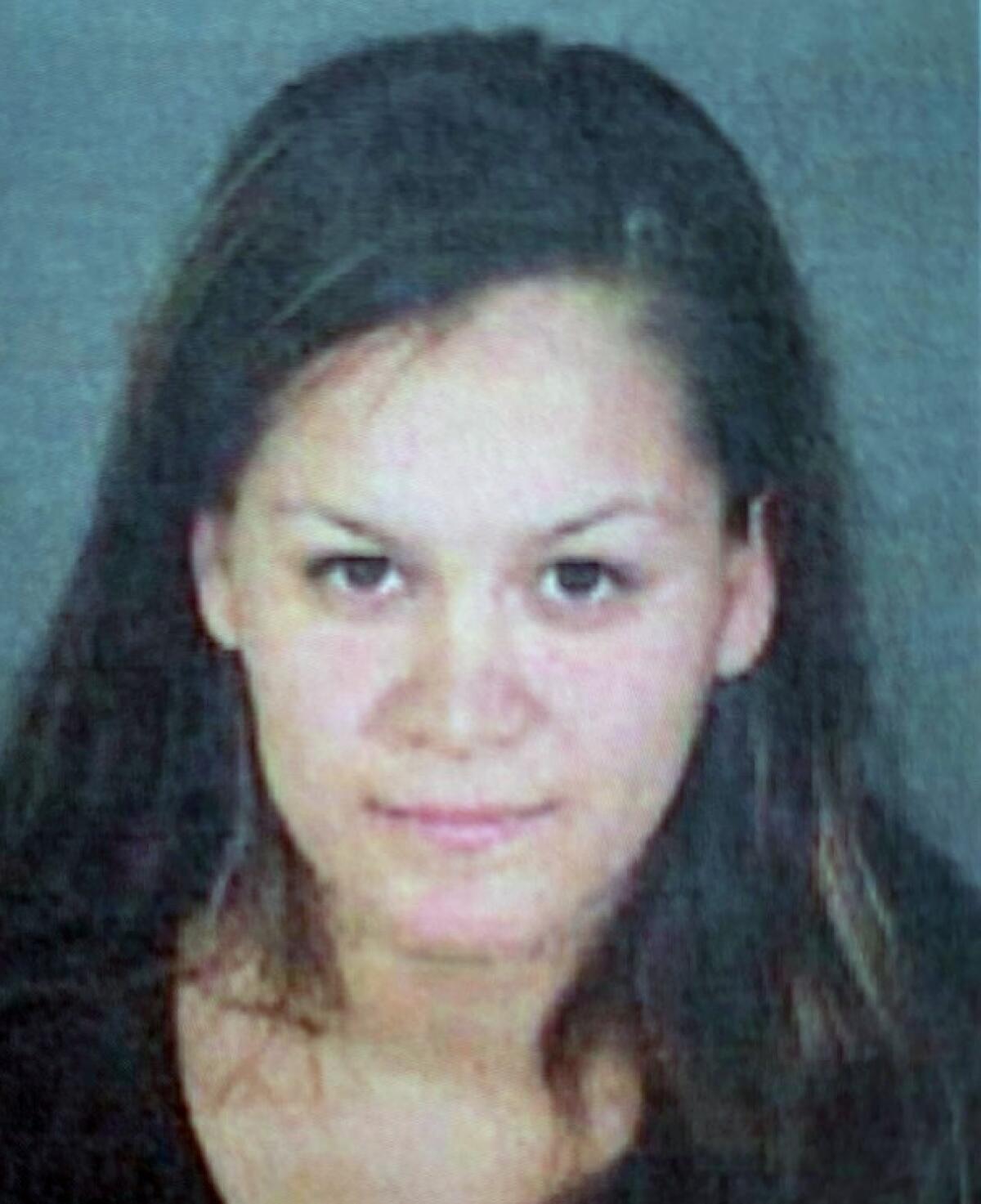

Then on Saturday, the children — Joanna, 3; Terry, 2; and Sierra, 6 months — were found dead inside an apartment in Reseda. Two of the children showed signs of being drowned, and all three had injuries that indicated they were bludgeoned. No cause of death has been publicly released. The LAPD has identified Carrillo, 30, as the suspect in their killings, and she was being held Monday in Tulare County jail on suspicion of second-degree robbery, records show.

L.A. County’s DCFS, the largest child welfare agency in the nation, declined to comment on the specifics of the Carrillo case, citing state confidentiality laws. In a statement, an agency spokeswoman said DCFS “joins the community in mourning.”

Denton, the children’s father, said in an interview and in petitions to a Tulare County judge that Carrillo had struggled with postpartum depression for years. She had expressed thoughts of suicide and often self-medicated with marijuana, he said in court papers, but in recent months, she had “lost touch with reality,” he said.

The child welfare agency in Tulare County appeared to have received warnings about the family in late February. At the time, Carrillo had accused the children’s father of participating in a pedophile ring in Porterville and allowing someone to molest one of their daughters, according to Denton’s account in court records and interviews. Police in Porterville were called to the home, Denton said in court papers, but the officer made no arrests.

Days later, around Feb. 26, Carrillo’s mother drove up from L.A. to pick up her daughter and their three children. Carrillo took the children’s legal documents, told Denton she “could go to Mexico,” where she has family, and for days afterward, refused to share their whereabouts, according to records.

A social worker from Tulare County reached out to Denton after he contacted a mental health hotline, and according to records later filed in court, he said the social worker expressed concern about Carrillo’s paranoid and agitated mental state and instructed him how he could petition a court to intervene.

Liliana Carrillo was arrested in Tulare County after leading authorities on a long-distance chase that included a carjacking, police say.

Denton secured an emergency court order for the children’s custody in March, and the judge required that any visits between Carrillo and the children be supervised at a special facility in Porterville.

Miller, the emergency room physician, said that she and Denton had then gone to L.A. County DCFS as well as the LAPD to notify the agencies that Carrillo had psychosis, had taken the children and was hiding in L.A.

LAPD Cmdr. Alan Hamilton said the department typically follows direction from DCFS in child custody matters.

“If DCFS told us they were going to the apartment and needed our help, we would have been there,” Hamilton said.

Miller and Denton said in interviews that they had several conversations with L.A. County social workers in which they both stated that Carrillo should not be alone with the children. One conversation with Denton lasted more than two hours, Miller said. Both recalled learning that a social worker at one point visited Carrillo but neither knew the specific date or nature of the encounter, but they both felt afterward that the agency was disinclined to view Carrillo as a threat.

“The social worker talked to Erik and said, ‘I don’t believe Liliana will harm these children,’” Miller said.

Carrillo received the order around March 12, according to records, and afterward, she went to the LAPD’s West Valley station, where Denton had requested she hand over all three children. There, an officer notified her of the consequences of failing to abide by the court order, according to a summary of the meeting Denton provided in court. Carrillo apparently opted to disregard the order.

After discovering Carrillo’s whereabouts, Denton and Miller said they also called the LAPD and begged police to take her to a mental health facility for psychiatric evaluation. Both told police Carrillo was a danger to the children and herself.

Denton said he was angry that after news of the children’s killings became public, the LAPD suggested they were unaware of Carrillo when they stated that officers had not gone to the home.

The mother of the children, 30-year-old Liliana Carrillo, was taken into custody in Tulare County after fleeing the scene.

Miller said two officers met them at a parking lot to discuss Carrillo’s mental health condition, and that officers even called a supervisor to the scene.

“I told them she might kill the kids. It should be on their body cam video from the night,” Miller said.

“Medically speaking, this was a clear psychiatric emergency,” she added. “If she came to my ER, and the family told me of these delusions and concerns, I would have held her for a psychiatric evaluation.”

Authorities further became aware of problems with the family around early April, when Carrillo sought a temporary restraining order against Denton and accused him of sexually abusing their oldest daughter, according to court records. Denton denied the allegation. Carrillo also made the abuse allegation directly to L.A. County DCFS, according to Miller, who said social workers did not perform a formal interview with Denton about the claim. In addition, Carrillo made an abuse allegation to DCFS against a friend of Denton, Miller said.

On Saturday, Carrillo’s mother discovered the three slain children in the apartment in Reseda, which prompted a massive search for Carrillo, who fled north.

Authorities alleged Carrillo drove north on Highway 65 but crashed her vehicle about 10 miles outside Delano. When another driver on Saturday came to her aid, she allegedly carried out a carjacking of the motorist’s silver Toyota truck, authorities said. Carrillo was eventually arrested near Ponderosa, in Tulare County.

For Denton and his family, they remain stricken by grief and frustrated by the missed opportunities to protect the children.

“Erik’s hands were tied by the law,” Miller said. “He jumped through every hoop placed in front of him to get the kids back safely.”

Since the coronavirus outbreak closed schools and largely hidden children at home, the reports of suspected abuse have dropped by as much as 50%.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.