Commentary: Her senior season was brief. For a dad and daughter, that small window was everything

I am staring at the blue mermaid with the yellow hair, because to stare at the teenager with the yellow hair, my daughter, is to risk crying. And I desperately do not want to cry. Not here. Not yet.

Last Wednesday afternoon, four of us sat inside a dimly lit office a stone’s throw from the pool deck of Aliso Niguel High in Aliso Viejo. The walls were the color of a Gulden’s mustard bottle, the floor a charmless slab of concrete. Medals from distant glories dangled in the foreground, dusty remnants of discarded youth.

Before me, to the left, sat Olivia Karich, senior co-captain of the girls’ junior varsity water polo team. Before me, to the right, sat Casey Pearlman, senior co-captain of the girls’ junior varsity water polo team.

They were in swivel chairs, listening as Danny Werner, the coach of the Wolverines’ varsity, peered out from behind a black facemask. He has a blue mermaid with yellow hair tattooed to his right arm.

Get the latest on the SoCal high school sports experience, including scores, news, features and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

“So here’s the deal,” Werner said, looking toward the captains. “Tomorrow is the last day the two of you get to play on this pool deck, and you’ll be doing so for varsity. I’m moving you up and you’re gonna start, and I want you to seize the moment. We’re playing for the league championship against Mission Viejo. You guys have gone through the craziest COVID year ever.”

A moment’s hesitation.

“You,” Werner said, “deserve this.”

The coach motioned for the meeting to conclude, and Casey spun her chair to face her father. Me. She was wearing a floral mask, but her eyes took the shapes of silver dollars.

Behind dark sunglasses, mine were red and teary.

::

Across much of the world, this was supposed to be the year for [fill in the blank].

Maybe it was supposed to be the year you moved to Guam. Or bought a Winnebago. Or started that sweet, new job. Maybe it was supposed to be the year you joined a Blind Melon tribute band. Jumped from an airplane. Learned Maltese.

For Casey Pearlman, Aliso Niguel High senior and veteran water polo player — my daughter — this was supposed to be the year she just had lots of fun.

I know that sentiment might seem underwhelming, especially down here in youth competition-mad south Orange County, land of lunatic travel parents and $1,000 aluminum bats and psychotic dreams of sausage-casing your kid into the next Mike Trout, the next LeBron James, the next Serena Williams. But for my daughter — bequeathed with the heart of a bull fighter and the athletic genes of a sportswriter — water polo has always been … recreation.

She picked up the sport 6½ years ago, shortly after our family relocated west from New Rochelle, N.Y. Casey was not an athlete, but my wife, Catherine, and I agreed she needed to do something, anything, recreational. A friend of a friend mentioned that her daughter loved this weird, wildly popular local endeavor called water polo, and before long Catherine was driving Casey to the Aliso Niguel High pool, where a man named Erick Lynch ran Aliso Aquatics, a local club with the stated mission of creating a “positive environment that will nurture our players love for water sports.”

Prep Rally delivers hot teams, highlights and answers to readers’ questions — the most thorough, dialed-in high school sports coverage in California.

Casey did not love water sports. Not on Day 1, when she could barely dog paddle a lap. Not two months later, when she competed in her first water polo tournament and spent the majority of her 30 seconds of playing time clutching the pool wall.

“On a scale of 1 to 100 in talent and ability,” Lynch recently told me, “Casey was a one.”

Over time, however, she discovered an affection for the rhythm of sports. Casey liked complaining about a workout, then doing it. She liked the adventure of bus rides. The togetherness of team meals. Group chats and mini-gossip and the comfort of a fixed schedule. She also liked that, as a rare southpaw, she arrived with a competitive advantage.

“That,” said Lynch, “gets you an extra look.”

Casey spent the first three years of high school on the frosh-soph and junior varsity squads, twice serving as captain. She is not a great water polo player — and she knows it. Where others launch fastballs, she uncorks slurves. Where others depend on brute strength, she looks for angles. She does not soar with a win. She does not mope with a loss. I’ve never actually seen her particularly bothered by losing, which is both weird and endearing.

Entering her senior season, Werner gave Casey a choice: “I told her she can be on varsity and I’d plug her in when the opportunities present themselves, or she could be on JV and be a leader and the captain of younger players. Either was fine with me.”

Casey chose leadership.

::

Over the last decade, Danny Werner has been named one of Orange County’s coaches of the year in both surfing and track and field — two of the three sports he heads at Aliso Niguel. The 48-year-old San Clemente native’s voice is loud, his right arm is coated in tattoos and he walks with a chest-out bravado that screams, “Follow me!”

Which is why he was somewhat befuddled when, last September, nobody seemed to think there would be a water polo season.

“I always had hope,” he says. “I really did. I believed, and I believed twice. But people were looking at me like I was crazy.”

When Aliso Niguel High began classes last Aug. 18, all students were required to learn from home. The water polo teams spent the first 1½ months of the academic year holding weekly Zoom chats. In mid-October, they were allowed to host team conditioning sessions, but only on land, and without balls. By early November, balls could be passed from player to player.

“You could see the numbers were gradually getting better,” said Werner. “And there was some optimism.”

In early December the teams finally started practicing in the water, five days a week. Opening games were scheduled for Dec. 28. Werner’s bright outlook was proving infectious. “It felt like everything might be changing for the better and we’d actually get to play,” said Taylor Kennedy, the varsity goaltender. “But it all fell apart.”

Shortly after the Thanksgiving travel boom, Orange County, like most of the rest of the state, saw its COVID numbers skyrocket. Seven members of the Aliso Niguel varsity girls’ team were diagnosed with COVID, as was Karich, the JV co-captain. Hers was the most terrifying of cases — the 17-year-old developed flu-like symptoms, then pneumonia and a 103-degree temperature, and her blood oxygen level plummeted into the 80s (the normal range is 95 to 100). Her parents rushed her to the emergency room in Irvine.

When it comes to super teams, few can top the Laguna Beach girls’ water polo team, which has 11 players who have signed with colleges.

Olivia was treated with monoclonal antibodies and gradually improved. So did the other COVID-infected players. In our house, Casey assumed her water polo career was over, and dove into her dueling passions of watching TikTok videos in her weathered rainbow chair and watching TikTok videos in her weathered rainbow chair while eating massive amounts of Costco taquitos. Kennedy, the goalie, landed a job at Old Navy. Her backup, Kenia Lyle, found work slinging grub at TK Burger.

Casey ultimately started scooping ice cream for $13 per hour at the nearby Cold Stone. It was something to do; a way to make lemonade out of a seemingly endless supply of moldy lemons.

And then, roughly three weeks ago, Werner was told that the Orange County COVID numbers were at a level that allowed sports to resume.

There would be condensed two-week, eight-game varsity and JV water polo seasons.

The coach was euphoric.

My daughter? Not so much.

::

Casey expressed some disdain toward a rapid-fire season, and I understood. So, for that matter, did Werner. “We’d practiced almost no defense and so much of what we did was in air, not water,” he said. “To expect players to just regain what they had — it’s asking a lot.”

Werner says the varsity option was open for Casey and Olivia. They could have joined the team’s bench players. Both declined. “There was a time when I thought having the varsity jacket would be cool, so maybe that would have been a reason,” Karich said. “But it’s a lot of money, and I don’t even have a school to wear it to. So what’s the purpose?”

Casey and the JV squad began their season last Tuesday, first with mandatory COVID tests (all clear), then with a 7-4 loss at nearby Tesoro High. It was an ugly game, with one miscue after another after another. Sluggish throws. Absent-minded blunders.

And yet, the joy was palpable. Werner has taken to referring to my daughter as “Captain Casey” — and it fits. Captain Casey likes leading warmups. Captain Casey likes showing younger players what to do. Captain Casey likes feeling needed. Plus, seeing my daughter swim again, her gangly arms slicing through the water, was a warm spring breeze. Through this year of inescapable darkness, I’d forgotten the simple pleasure of watching someone you love do something she loves.

A few days later, shortly before another JV game was to begin, I found myself standing alongside Karly Kennedy, mother of the varsity goaltender. We were discussing nothing in particular, when I noticed she was crying.

“I’m not upset,” she said. “Just filled with all sorts of emotions.”

I understood.

::

If I’m being honest, I have sometimes failed to understand Casey’s reluctance to play varsity.

Having grown up in sports, the goal was always to fight the hardest, run the fastest, demand excellence. You competed to win. And while it was OK to fail, I at least wanted to square off against the very best.

But now it is last Thursday afternoon, Senior Day at the Aliso Niguel High pool, and Casey is uncomfortable. She and Olivia are — for the moment — members of varsity because they have been told it is an honor, and the thing to do, and the natural progression for players who have been around the program for this long. But … it doesn’t feel right. This is not their team. These are not their teammates. To celebrate the occasion, large photographs of the seniors are hung alongside the pool, but Casey and Olivia are (inadvertently, I have no doubt) excluded. I see the hurt on my daughter’s face, and it takes me back to the earliest days of preschool, when tiny Casey — fruit punch red lips, Cinderella dress — refused to let go of my leg.

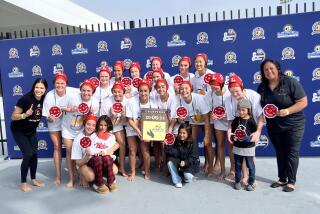

We shuffle through the motions of a short pregame ceremony — the wife and I presenting Casey with a bouquet of flowers, the three of us posing for a photo. It is Mission Viejo at Aliso Niguel for the Sea Valley League title. Casey lines up against the wall, the referee blows a whistle, the game begins.

My hands are sweaty. My heart is thumping. I want today to be great. I want Casey to excel and feel confident and happy and ...

::

She is pulled after 60 seconds.

She never returns.

And here’s the thing — the craziest of things: I am happy, and she is happy. The varsity girls are serious and physical and a bit out of her depth. The parents standing by the side of the pool, barking toward their children and shooting angry glares toward the referees, are toxins.

I watch Casey throughout the action, and she and Olivia are bobbing in the water, smiling, laughing, chatting away, two young women on a picnic, or a leisurely stroll, basking in the closing days of their childhoods.

It made me think back to something Erick Lynch, Casey’s first coach, had told me a few days earlier. We were standing by a pool, and I asked if he felt any disappointment that the raw, lanky left-hander from New York never developed into a water polo supernova.

Lynch looked at me with disbelief.

“Jeff,” he said, “Casey came to me and she couldn’t swim a lap. Now look at her — she’s the JV captain, she’s a senior who loves water polo and stuck with it, she’s happy and she’s gotten so much out of the sport.”

He paused, as if for emphasis.

“All these years of coaching,” he said, “and your daughter is probably my greatest success.”

Jeff Pearlman, an Orange County resident, is the author of “Three-Ring Circus: Kobe Shaq, Phil and the Crazy Years of the Lakers Dynasty.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.