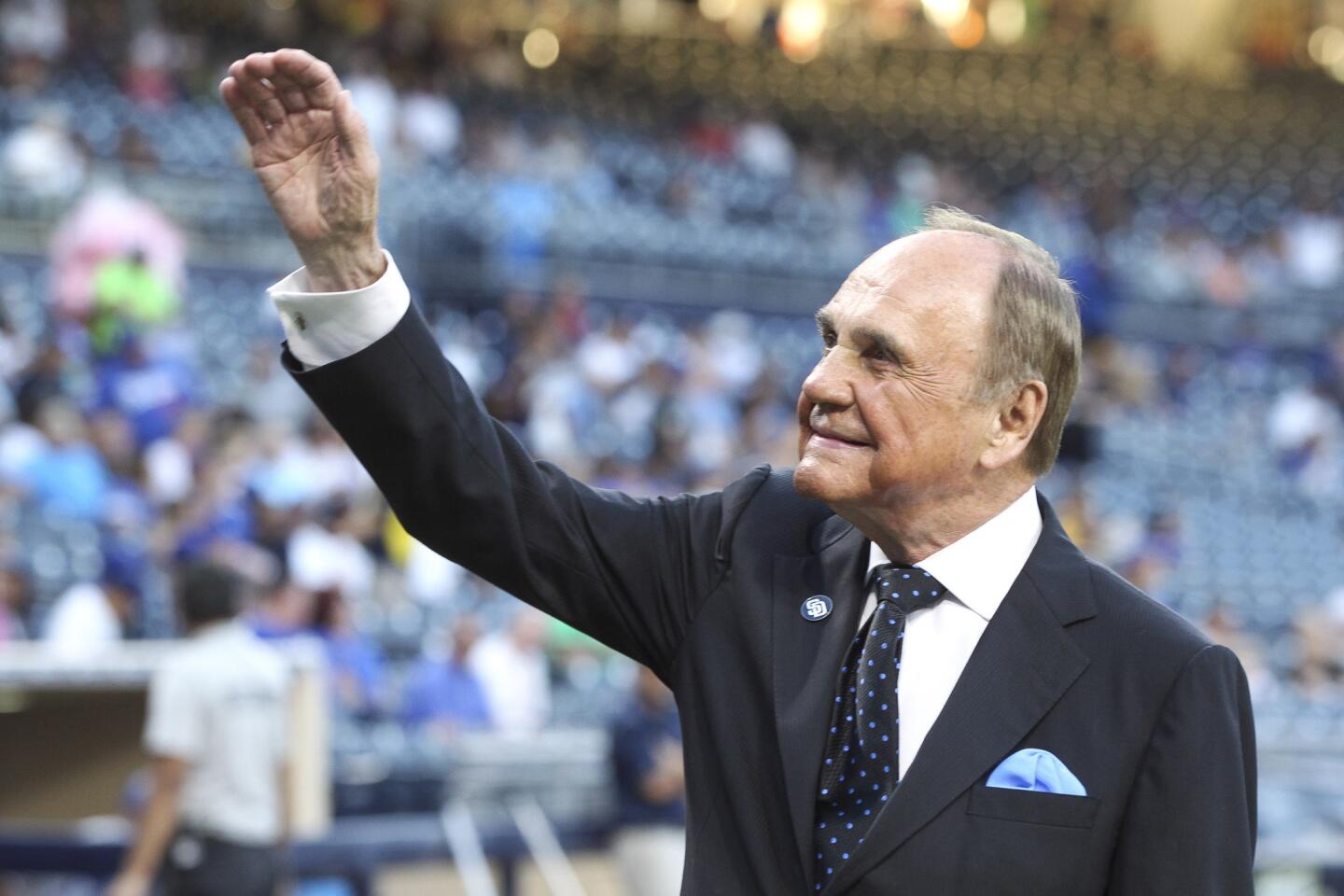

An appreciation of Dick Enberg, who was ‘Vin Scully spread over a dozen sports’

From those in the sports journalism business, the next few days will bring a deluge of Dick Enberg stories. Few before him have been so deluge-worthy.

In a recent podcast, TV executive Andy Friendly called Enberg “broadcast royalty.” Well said.

Enberg, who died Thursday at 82, was Vin Scully, spread over a dozen sports. Scully’s worship was focused, emanating from those who found religion in bats and balls and warm summer days. Enberg’s was also bats and balls, as well as tennis racquets, golf clubs, shoulder pads and squeaky sneakers on hardwood floors. Even racing bicycles.

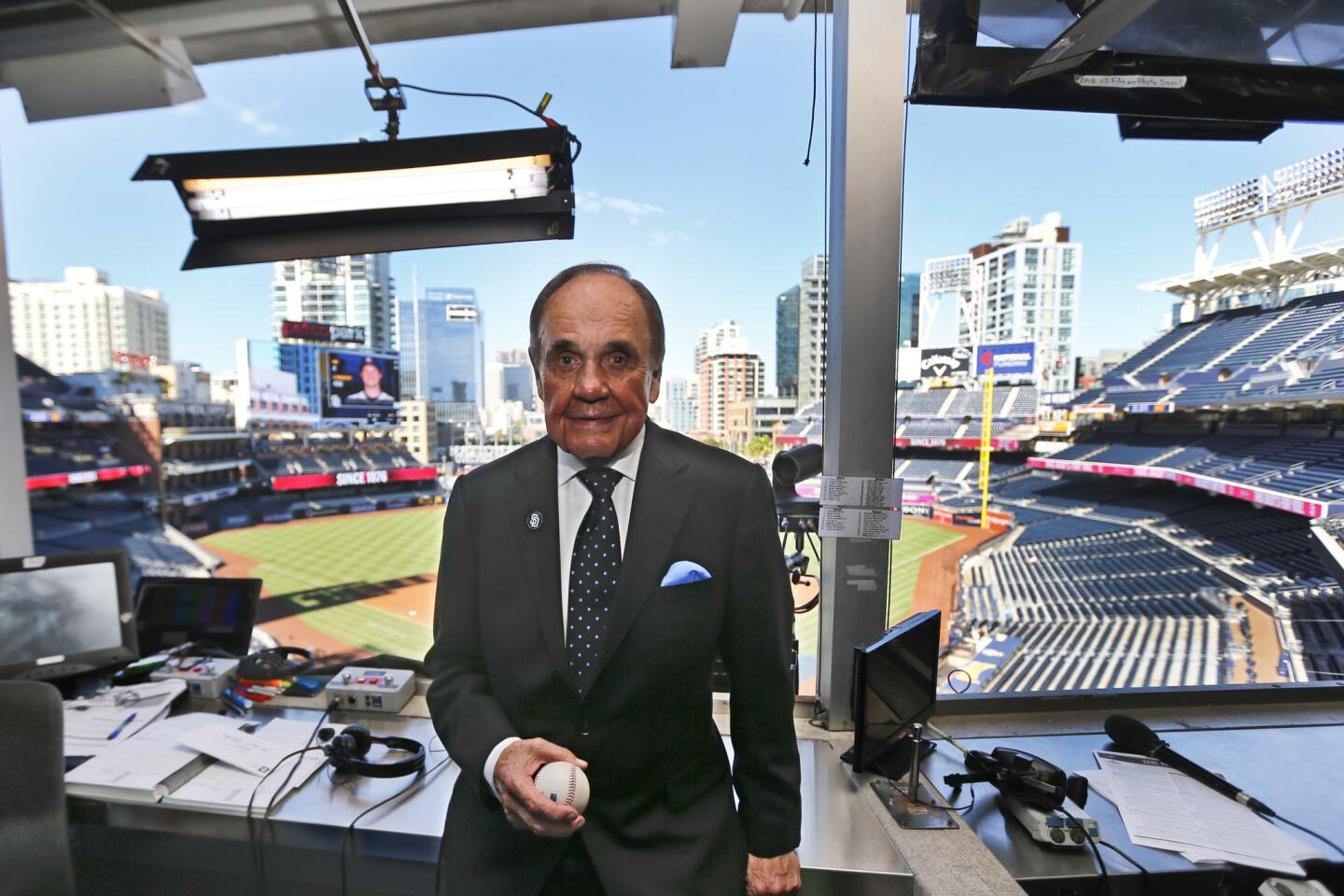

If there was a gymnasium, field, court or fairway, and there was a microphone nearby, chances are Enberg was sitting behind it.

He broadcast eight of UCLA’s NCAA basketball title teams. He did nine baseball no-hitters, or two more than Nolan Ryan pitched. He did the famous UCLA-Houston game in the Astrodome and tried for years to explain to John Wooden why it was OK for the Bruins to lose that one, because a victory by Houston and Elvin Hayes meant more to the sport than just another UCLA win. Surprise, surprise. Wooden never agreed.

Enberg did Super Bowls that were super, tennis tournaments full of love, major golf events where his descriptions were sweeter than the winner’s swing. He even did the first radio play-by-play, or pedal-by-pedal, of Indian University’s Little 500, a bike race later memorialized in the movie “Breaking Away.”

Of the million words he spoke to the public, all recorded, many rehashed over the water cooler, he made incredibly few mistakes. One was during his presentation of the women’s singles trophy at the 2007 U.S. Open.

The winner was Belgian star Justine Henin. Enberg introduced her as Justin Henin-Hardenne, which she was until a few years prior, when she dropped the “Hardenne” in the wake of an unpleasant divorce. Later, I walked past him in the press center. I didn’t say a word, but apparently had the usual cynical look of a newspaper guy. He looked at me, shrugged, and said, “It just came out.”

Any deviation from perfection bothered Enberg.

You didn’t take lightly special time spent with him.

Mine was at a couple of dinner tables and, later, sitting in his car behind Pauley Pavilion after he had finished UCLA basketball broadcasts. Enberg was writing his one-man play on Al McGuire, his longtime college basketball broadcast partner, and he knew I knew McGuire well, from my days as a Milwaukee newspaperman and McGuire’s days as Marquette’s basketball coach and character extraordinaire. There had never been anybody like McGuire. Never will be. We both knew that.

So, I became the pseudo-editor. Enberg would write something, I’d read it and say yay or nay. Enberg may have been broadcast royalty, but he wasn’t a prima donna. He knew that writing wasn’t the same as broadcasting, that the written word usually produced more head-scratching and agony than that which is spoken. The sessions always went the same way. He’d tell a McGuire story and we would laugh until our stomachs hurt. Then I’d tell one. Same thing. The dinner sessions would necessitate ordering another drink. In the car, we would just roll down the steamed-up windows.

Most of the time, the conclusion we reached was the same. You can’t use that. Eventually, Enberg had to get a professional screenwriting editor, one who knew nothing about McGuire and would not muddy the creative-process waters like I did. His one-man play, eventually performed all over the country by Cotter Smith, was called “Coach.” I had pushed for “Nut-Job Al,” but Enberg was too kind a person to have that.

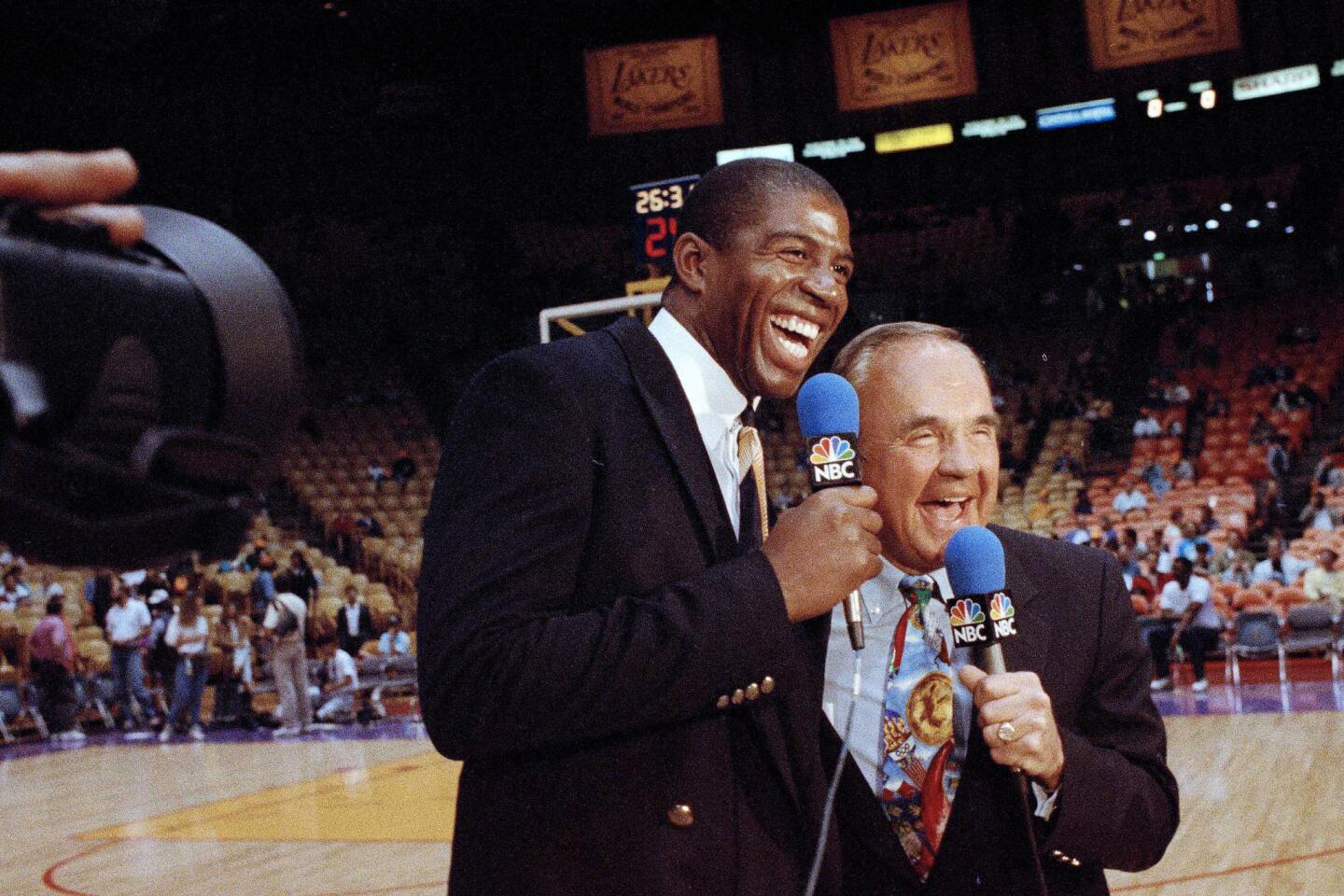

I always felt that the sports broadcast industry had a sequel to sportswriting’s Bud Collins. Collins would help every new writer. He would sit down and spend the time, mold the new minds. Enberg was that for sportscasters.

Ron Fairly, the longtime Dodgers star and 30-year veteran of baseball broadcasting, writes of that in his soon-to-be-released memoir, “Fairly at Bat: My 50 years in baseball, from the batter’s box to the broadcast booth.”

Fairly writes that he was a newbie to the booth when the Angels put him on a series of telecasts with Don Drysdale and Enberg.

“Enberg got me started,” Fairly said Friday. “He told me, first, that it might be more difficult to do the color commentary than his play-by-play. He said if he called a play like: ‘There’s a ground ball to shortstop, who goes deep and to his right, plants his feet and fires to first, where the throw is dug out,’ I shouldn’t say the same thing. I had to avoid repeating that. So, I remember talking about how the shortstop had to position his feet to get to the right spot. It was my first lesson, and I never forgot.

“He also told me to keep my comments short, and he showed me how to keep a proper scorebook, so I had everything in front of me for quick response. He was a great teacher, a great person.”

Did he have any McGuire stories? “Oh, yes,” Fairly said, “but I can’t repeat any.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.