Harmonica Star Sticks With the Blue Notes

James Cotton says he never gave a thought to becoming part of the Chicago blues boom of the 1950s. Then, as quickly as Saturday night turns into Sunday morning, he was on the road north from Memphis in the illustrious company of Muddy Waters.

Cotton’s acceptance into the Chicago blues scene was immediate--after all, Muddy Waters had handpicked the Mississippi-born teen - ager to come to Chicago and fill the harmonica slot in his band that previously had belonged to such masters as Little Walter Jacobs and Junior Wells.

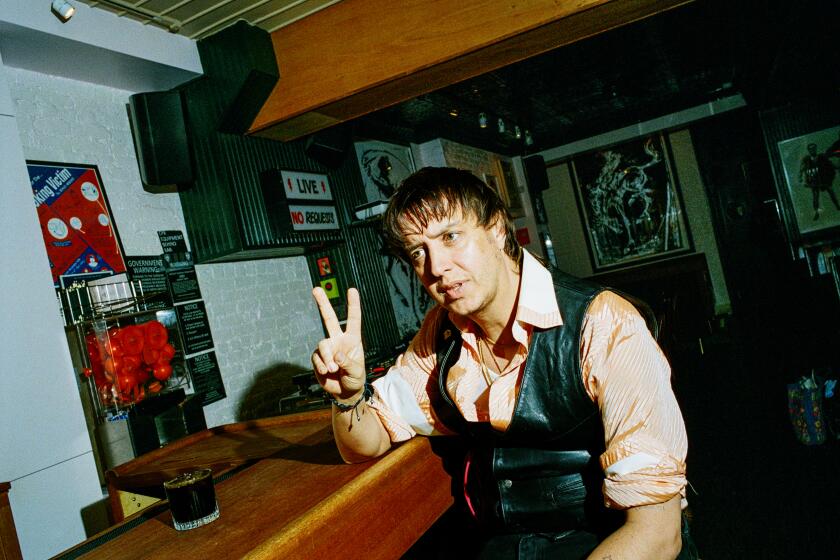

Today, Cotton, 54, is a still-active veteran of the ‘50s Chicago blues boom. He’s part of a generation of players who began their lives on Southern farms and wound up in urban clubs, creating a brand of electric blues that has proved enduring in itself and crucial to the origins and development of rock ‘n’ roll. And he continues to tour without letup--Cotton will lead his band Wednesday at Winston’s in Ocean Beach.

Cotton may have had a fuller blues tutelage than anyone alive. Speaking recently from a tour stop in Manchester, N.H., he recalled in a throaty, heavy-as-burlap voice how his mother taught him his first licks on the harmonica when he was a mere tot in Tunica, Miss. But Cotton said it was his uncle, Wylie Green, who first saw his precocious potential. According to Cotton, it was what he could do on a farm tractor--as much work as a grown man--that convinced his uncle that, even at age 9, the boy had the maturity to fend for himself in the world.

Since Cotton’s real genius was for the harmonica, his uncle brought him to Helena, Ark., where blues harmonica player Aleck (Rice) Miller, better known as Sonny Boy Williamson, performed on radio. Somehow, Cotton says, his uncle prevailed upon Williamson--the author of such future rock standards as “One Way Out,” (done by the Allman Brothers) and “Eyesight to the Blind” (incorporated by the Who into their rock opera, “Tommy”)--to take the boy on as a ward. Cotton spent six years with Williamson, watching and learning.

At 15, Cotton struck out on his own and landed in West Memphis, Ark., on the outskirts of Memphis, Tenn. With his own band, he recorded for the famous Sun label that was soon to spawn the rock ‘n’ roll of Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins and Jerry Lee Lewis. Cotton also served a further apprenticeship as sideman to blues great Howlin’ Wolf.

As for heading north to latch onto the burgeoning blues scene in Chicago, Cotton said, “I never thought of it in my life.” Until, that is, Muddy Waters turned up one night in 1954 and offered him a job in his band.

“He came to this little beer joint where me and this guitar player were (performing) on a Saturday evening,” Cotton recounted. Waters, needing a harmonica player to round out his band while on tour in Memphis, had been directed to Cotton.

“He said, ‘I’m Muddy Waters,’ and he said he wanted to give me a job.” Cotton’s first reaction was to look on this supposed benefactor with suspicion. Of course, he’d heard Muddy Waters on record. But he’d never seen Muddy Waters.

It wasn’t until Cotton went to where Waters was playing that night that he became convinced.

“I saw the posters with his picture on ‘em. I thought, ‘Maybe this is the right cat.’ I never dreamed I’d be going to Chicago or playing with Muddy Waters. But I played in Memphis (with Waters) that Saturday night, and that Sunday morning we were off to Chicago.”

While it sounds as if Cotton had an easy accession to the Chicago blues, he in fact found himself in a nerve-racking position.

“Little Walter Jacobs was in Chicago, one of the greatest harmonica players that ever lived. There was a whole lot of pressure on me. I had to learn how to play harmonica all over again. It made a musician out of me.”

Early on, Cotton said, Waters commanded him simply to replicate the famous harmonica parts that Jacobs had created on Waters’ records. It wasn’t until Cotton participated in some successful recording sessions that he found some leeway to forge his own identity.

“When we started to get hit records together, (Waters) had to respect it, because I wrote some of them,” including “Trouble, No More” and “Sugar Sweet.”

After 12 years with Waters, Cotton left to form his own band, with an eye toward experimenting with a funky, more rock-oriented style of blues.

“I respected him so much, but there were other things that I wanted to play, and I would never mistreat him with his music. If it was rock ‘n’ roll, he didn’t want to touch it. But I felt that if I can play an instrument, I should play whatever I want.”

Today, Cotton says, he still has an ear for all sorts of music, from symphonies to rap.

“I listen to everything,” he said when asked about rap. “I can’t do it, but I listen to it. They make a lot of money doing it, God bless ‘em. Even if I tried it, it would come out like the blues.”

In fact, Cotton’s recent albums mark a return to the pure, basic Chicago blues style. “Live at Antone’s,” on the Texas-based Antone’s label, and the current “Take Me Back,” on San Francisco’s Blind Pig Records, both received Grammy nominations.

Even with a schedule that keeps him on the road 45 weeks a year, Cotton says he never has lost his enthusiasm for playing.

“Twenty-four hours a day, every day, you’ll catch me with a harmonica,” he said. “I sleep with ‘em in the bed with me. I play for the truckers on the CB when we’re driving down the highway. The highway is my home, and my Dodge van is my bed, and the blues is my companion. I’m going to do it till I die.”

But what about home life--isn’t that something he misses?

“You can’t miss something you never had,” said Cotton, who has rarely-used homes in Memphis and Chicago.

Cotton says he is delighted and encouraged by the recent success of Bonnie Raitt, a blues protege, and John Lee Hooker, a blues progenitor. Raitt won four Grammys last month (one of them shared with Hooker for Best Traditional Blues recording), and Hooker’s album, “The Healer,” is a Top 100 album that is approaching gold record status (500,000 sold)--an astonishing crossover success for a septuagenarian traditional blues man recording for a small label, Chameleon Records.

“I saw Bonnie Raitt on TV, getting four Grammys, and I jumped out of the bed,” Cotton recalled. “I’m so proud, I don’t know what to do. I think things like that (Hooker’s and Raitt’s success) come in time, when the time is right. You have to be consistent and hope the sun will rise and shine for you one day.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.