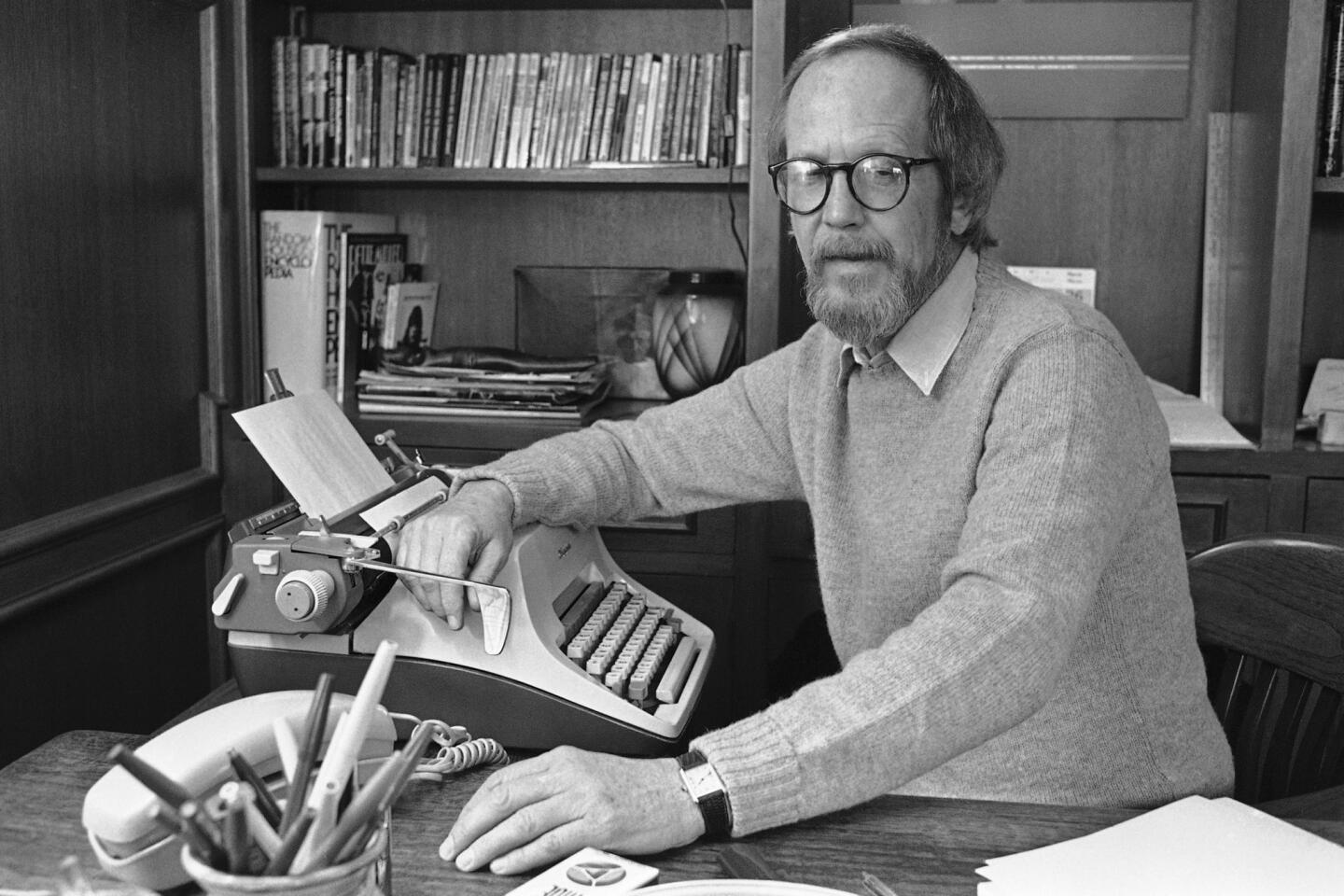

Matt Mattox dies at 91; master Hollywood dancer and choreographer

- Share via

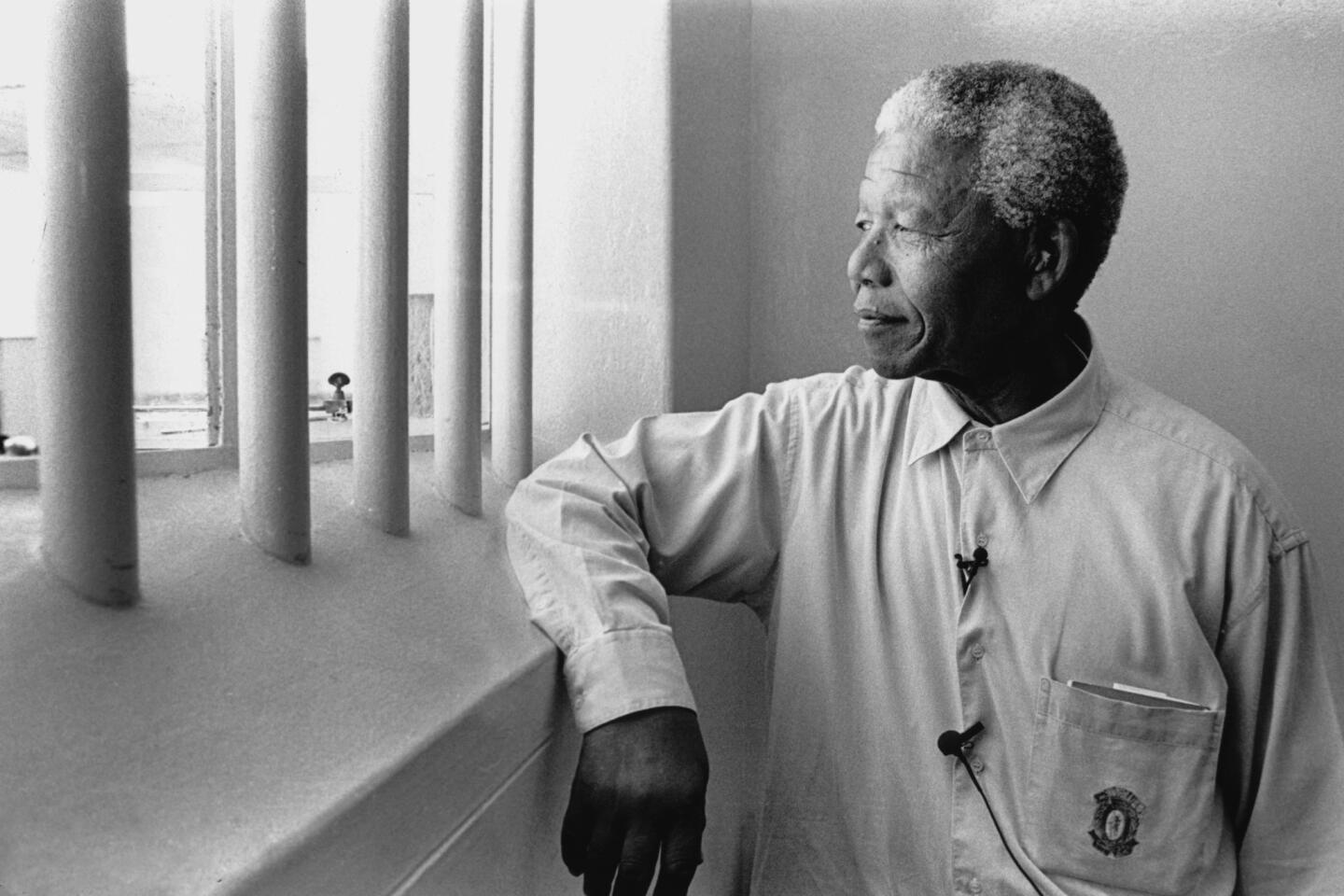

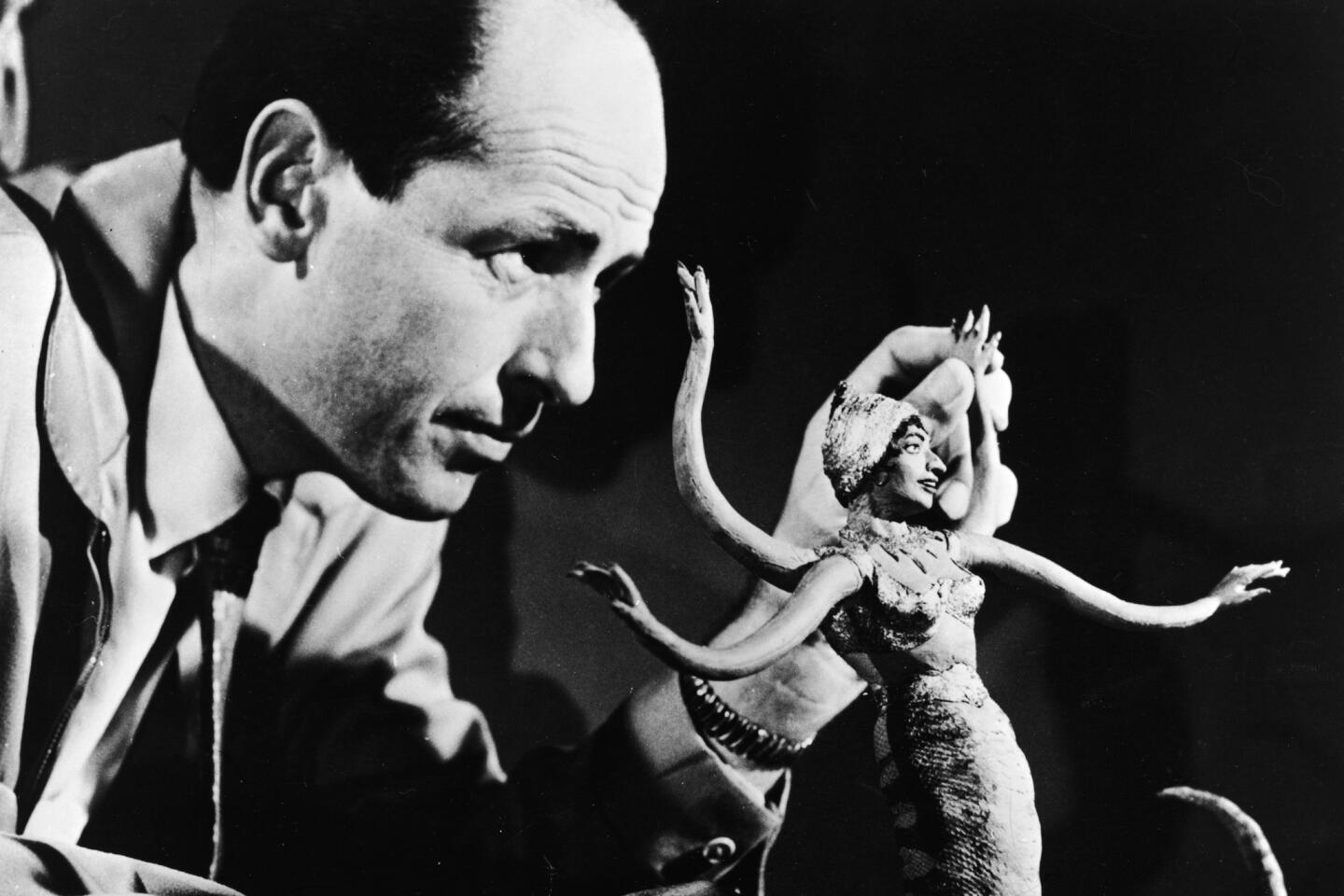

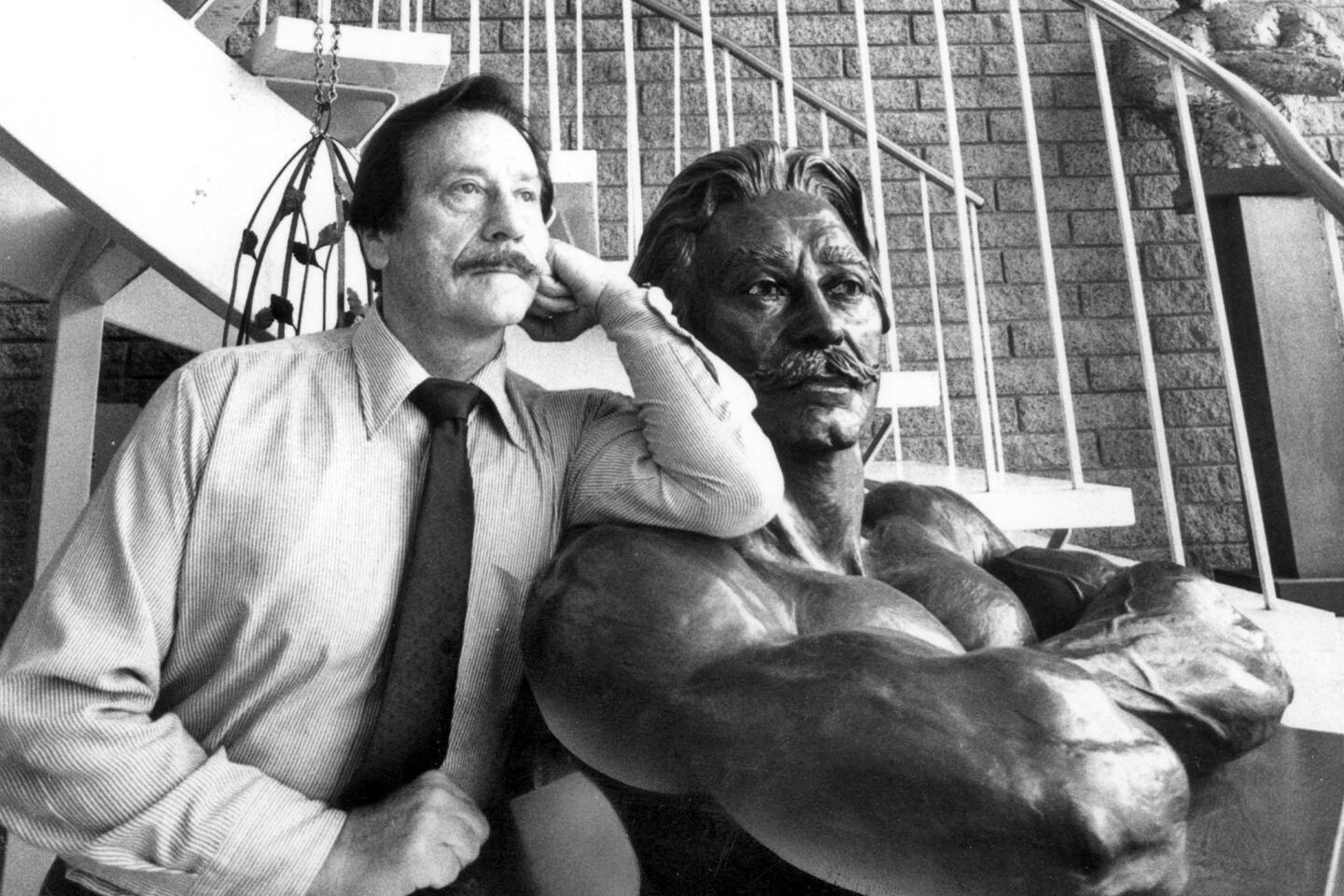

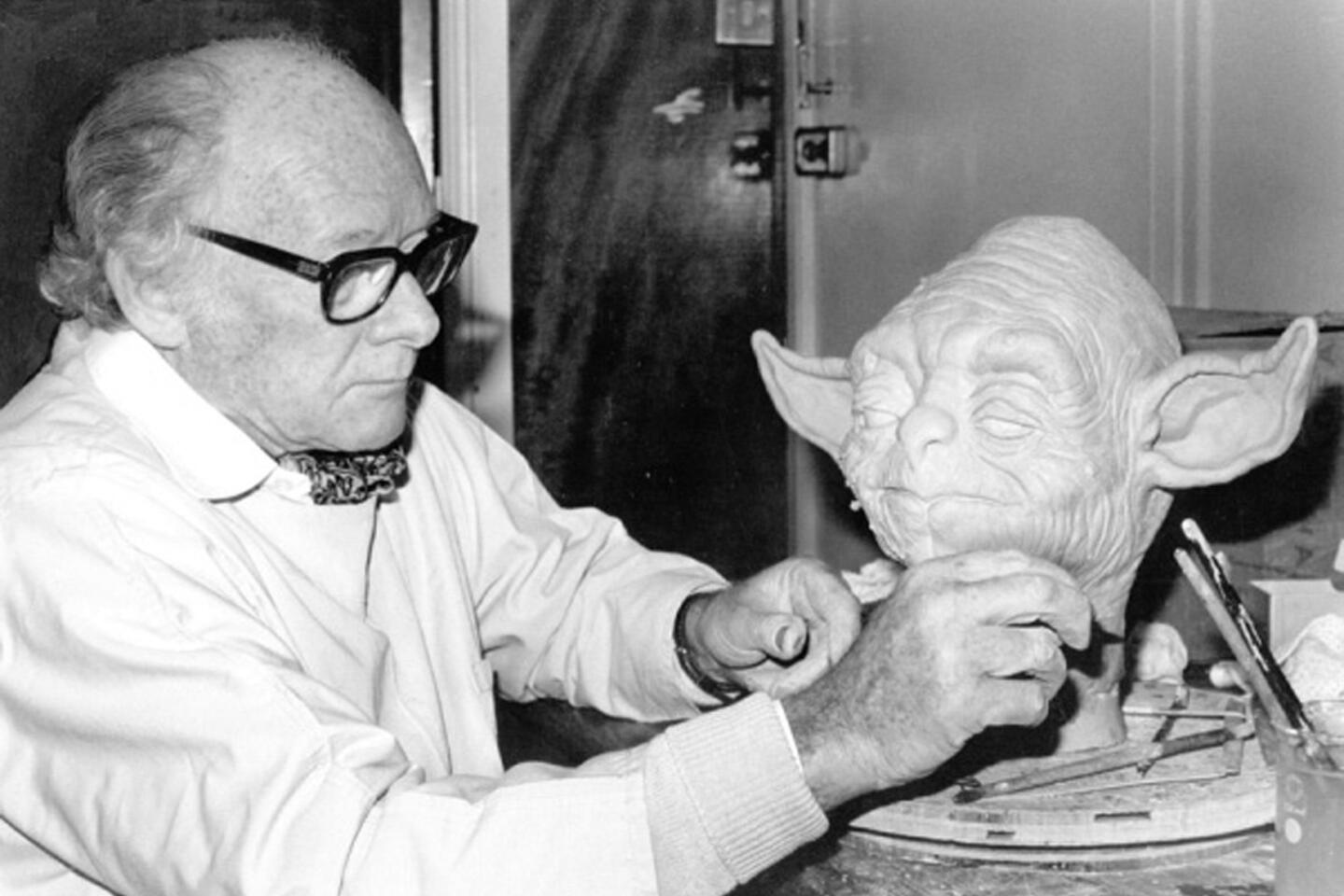

Hollywood considered Matt Mattox one of the best dancers in the country when he was cast to dizzying effect in “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers,” the 1954 Oscar-winning film celebrated for its imaginative and masterful dance moves.

Billed as one of the “frontier Romeos” in the musical set in the American West, the classically trained Mattox memorably vaults over a sawhorse, pirouettes on a plank and poetically wields an ax in striking choreography by Michael Kidd.

“Everyone on the movie set agreed that he was the best dancer of all,” Jacques d’Amboise, who was a leading figure in American ballet when he danced alongside Mattox as one of the film’s rowdy brothers, said this week in a French media report. “He’s up there on Mt. Everest with Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly.”

The tall and dashing Mattox “had enormous strength, versatility, precision and technique,” Kidd once said, and was “always the first person” the choreographer wanted for the movies he made at MGM.

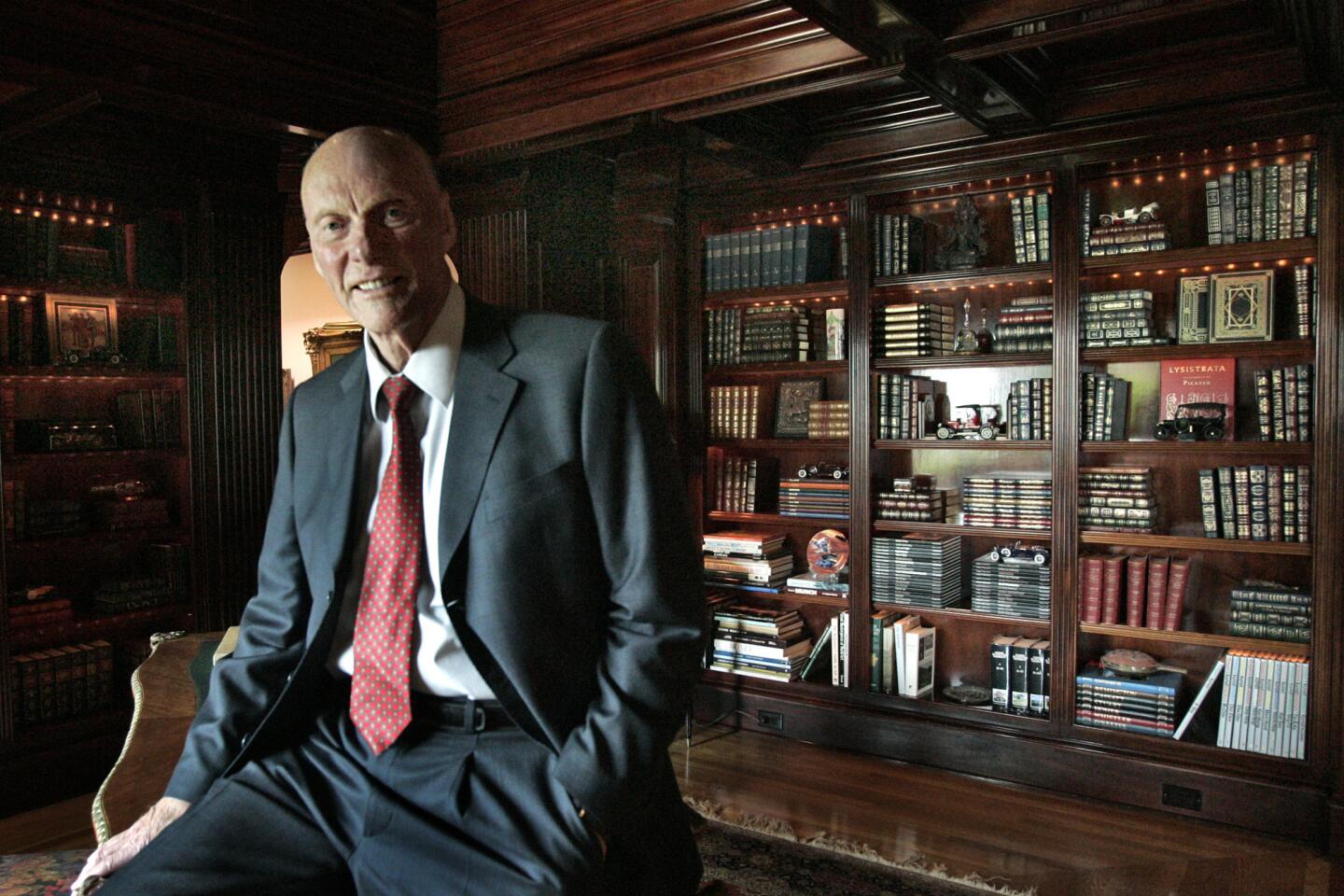

Yet Mattox yearned to concentrate on teaching and choreography — “to be an artist” — and in the mid-1950s largely abandoned his decade-old movie career. He headed to New York City and then Europe and became a major figure in the evolution of jazz dance.

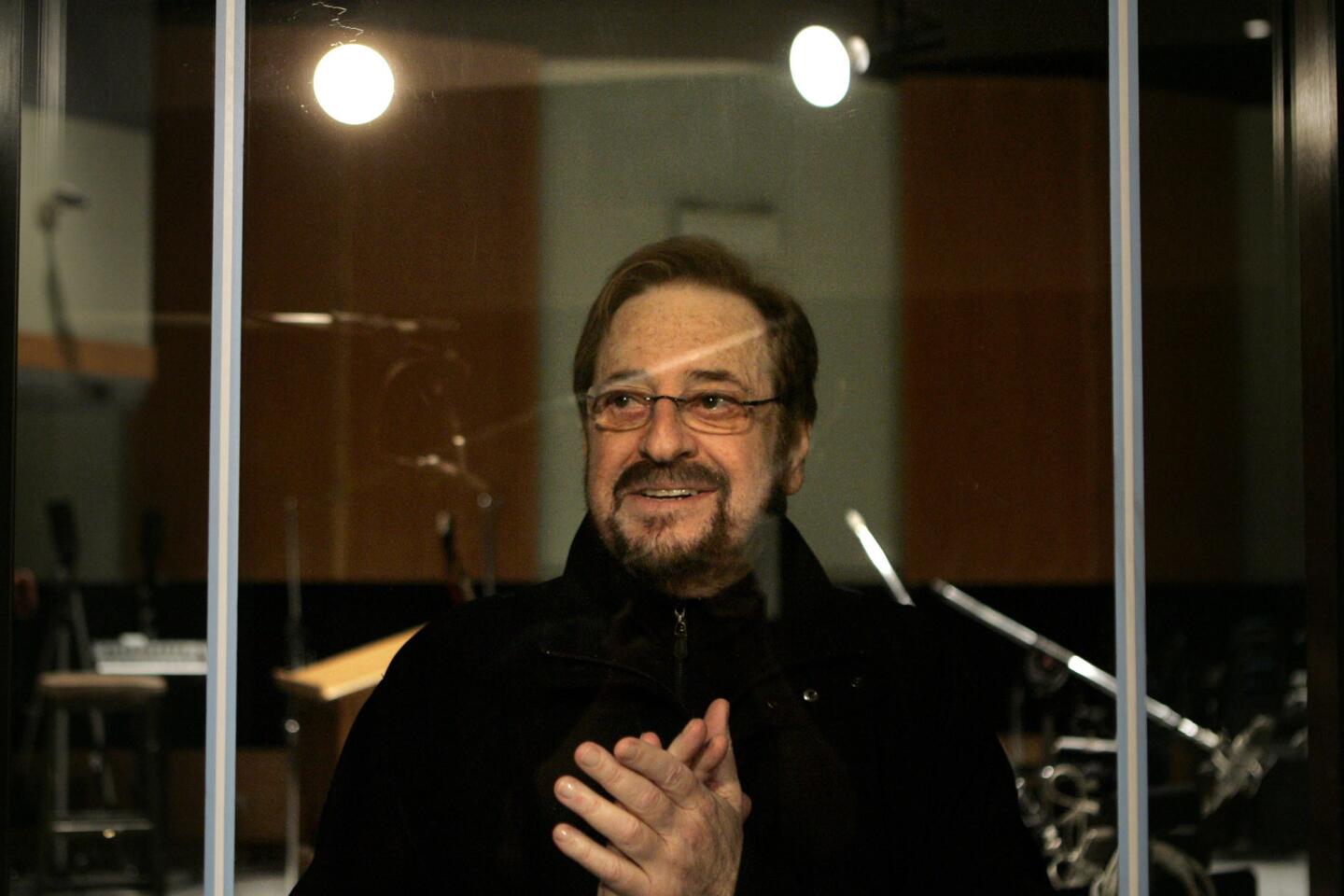

Mattox, 91, who developed an influential method of teaching jazz dance, died Monday in France, his family announced. He had lived in southern France since 1980.

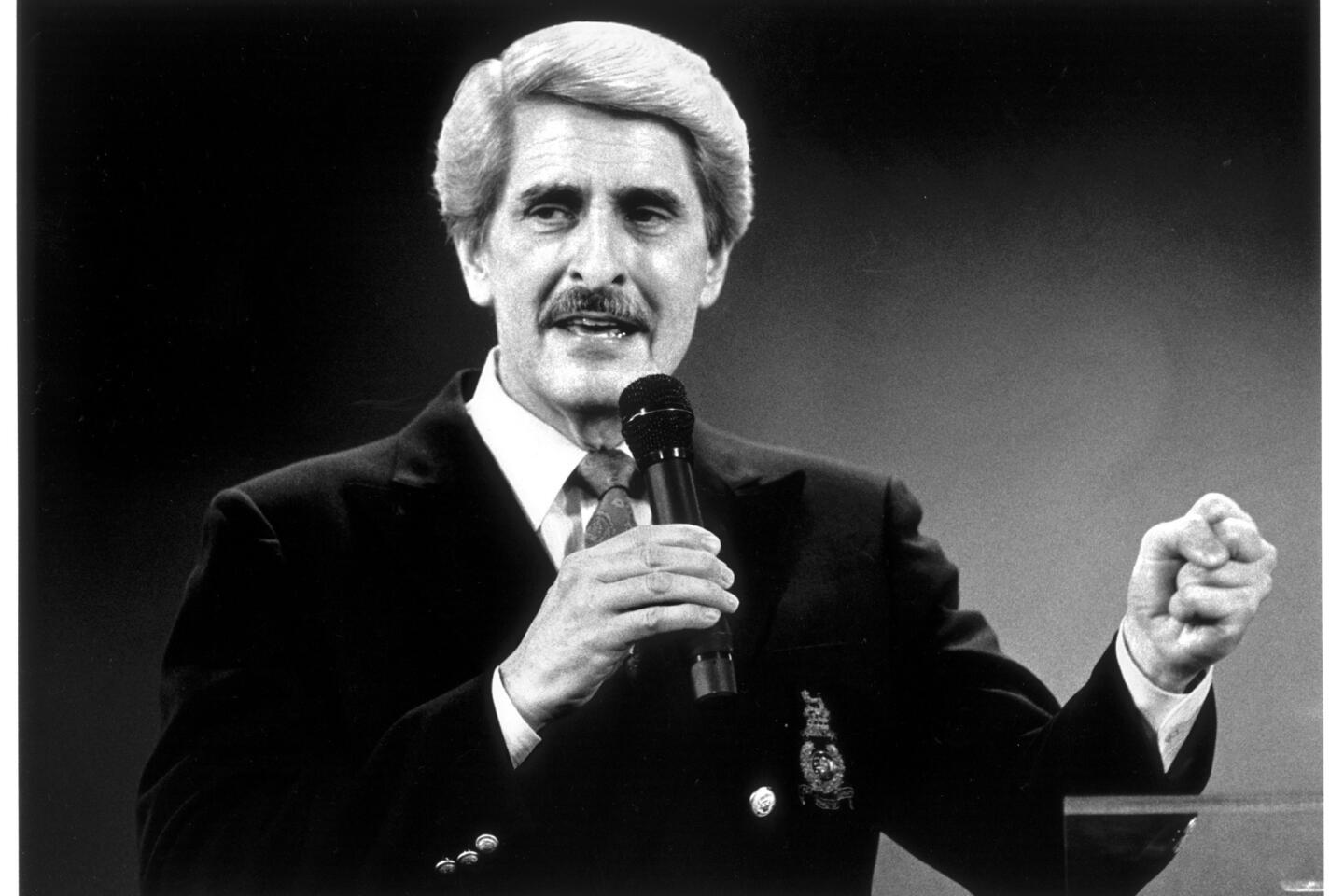

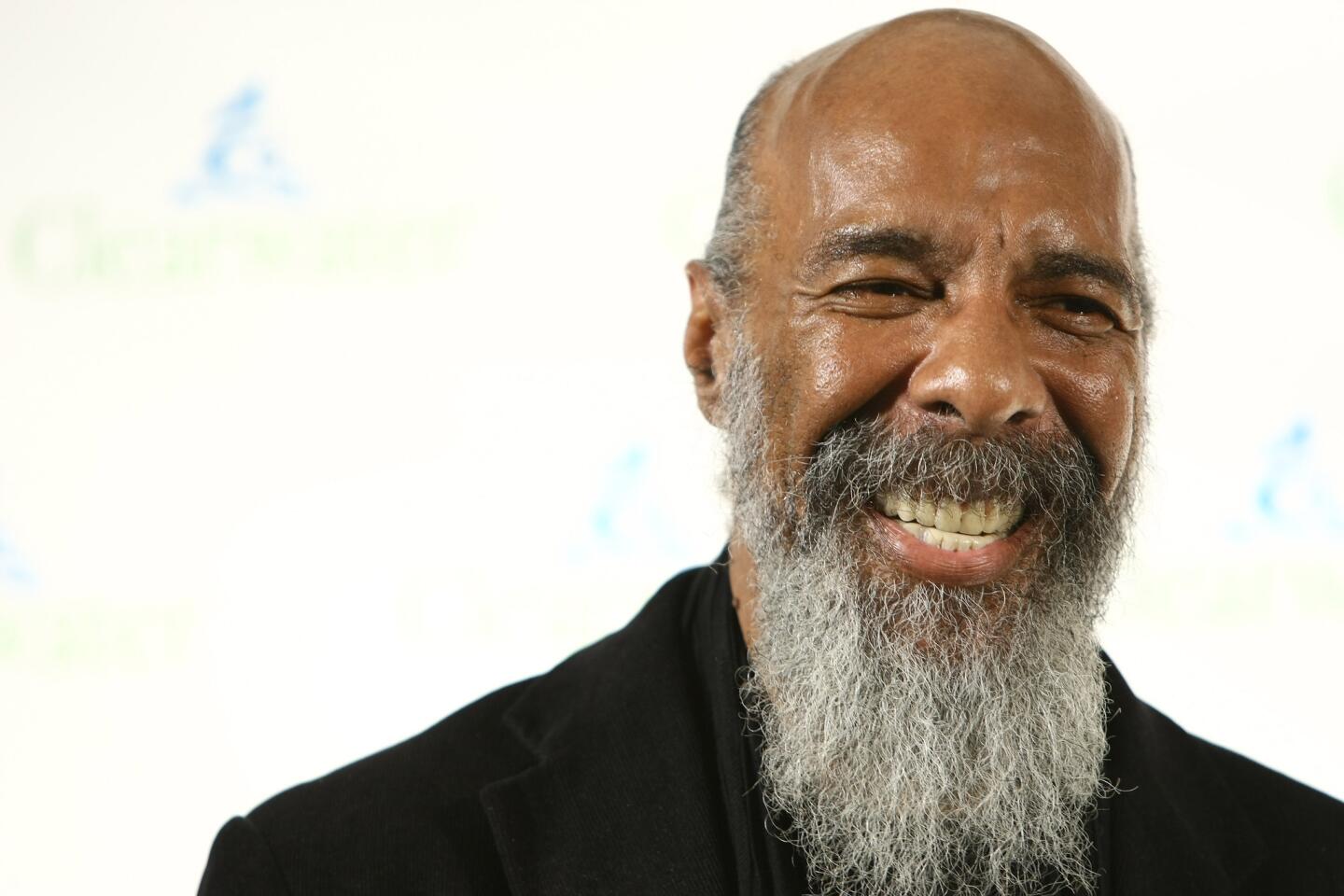

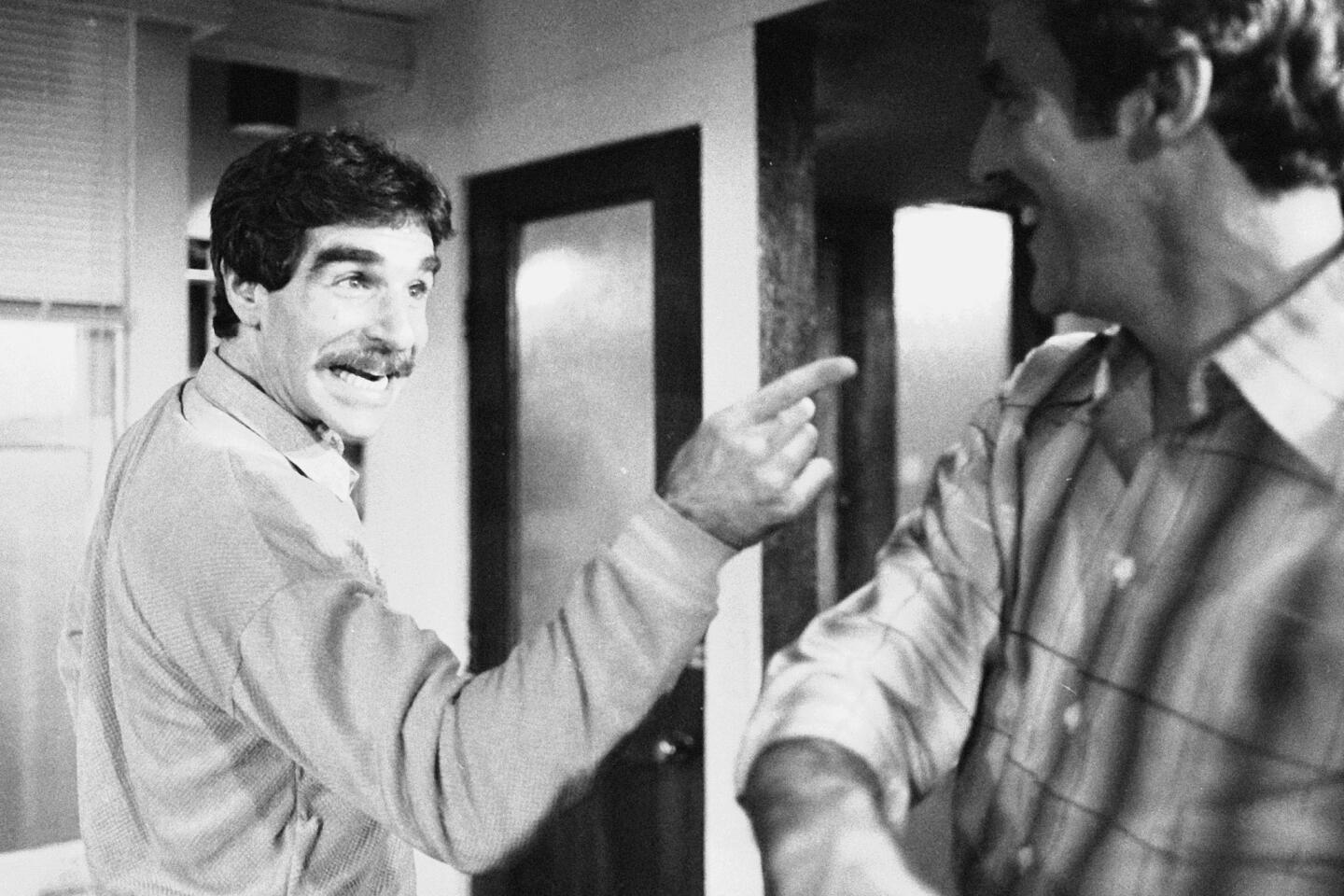

“He was superhuman. This guy could do anything,” said Bob Boross, a dance professor at Radford University in Virginia who studied with Mattox at a rare U.S. workshop he gave at UCLA in 1986 and later wrote his graduate thesis on him.

Living overseas since 1970 had caused Mattox’s fame “to recede somewhat in America,” Boross said, “but in Europe, he is widely known as a big catalyst for its jazz dance scene.”

Born Harold Henry Mattox on Aug. 18, 1921, in Tulsa, Okla., he moved to San Bernardino in the 1930s with his parents, who worked in sales.

He once said he learned to dance at age 5 from a black porter and counted a female vaudevillian among his teachers. He spent more than a decade studying ballet.

“The finishing touches,” he recalled in 1980 in the Christian Science Monitor, were applied in Los Angeles by tap great Louis DePron. Mattox considered the six years he took tap to be the bedrock of his jazz technique.

His dancing career started when he was 11, at the Fox Figueroa Theatre in Los Angeles, he recalled in 1984. Except for the two years in the Army Air Forces during World War II, Mattox said he’d “been dancing ever since.”

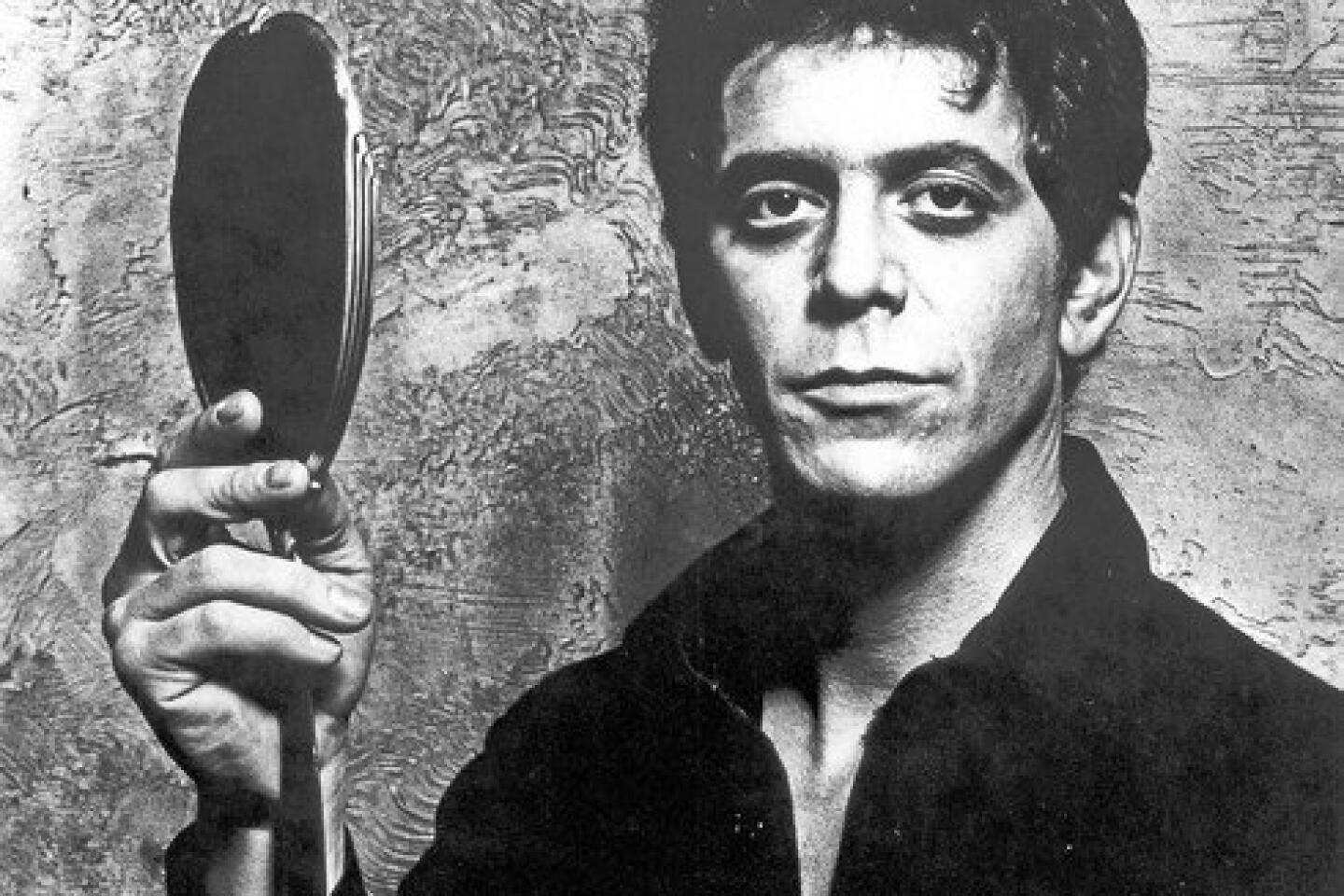

With several films behind him — including 1945’s “Yolanda and the Thief” with Fred Astaire — Mattox was still planning a career in ballet when theatrical jazz-dance pioneer Jack Cole hired him in 1948 to dance in “Magdalena” on Broadway. Cole became his mentor and helped steer Mattox toward the jazz technique.

He refused to call his method “jazz dance,” preferring “freestyle” because the term was more inclusive and reflected wider creative choice and movements.

In film and on stage, Mattox “brought his fast-moving precision and seemingly boundless energy,” The Times reported in 1984.

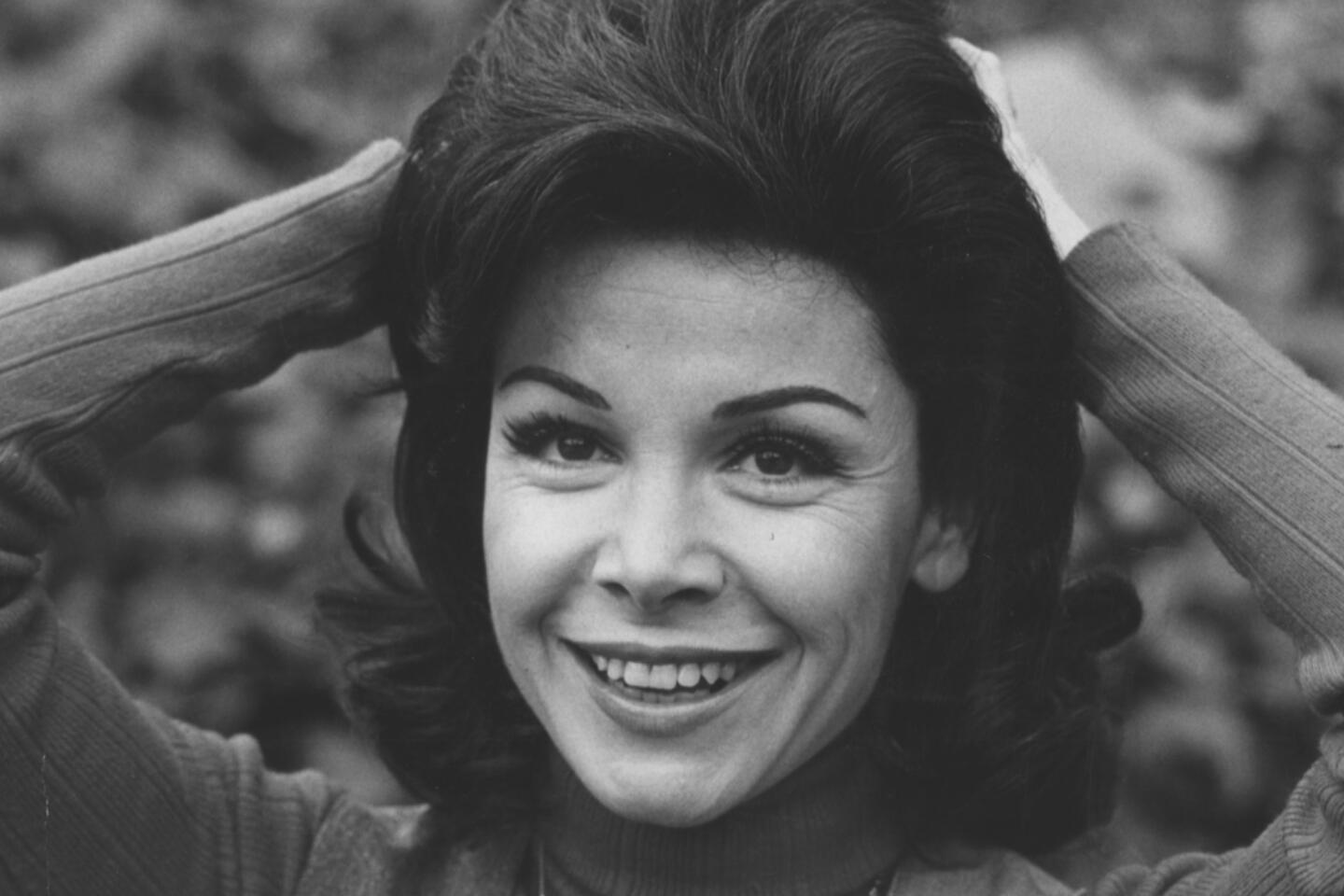

On Broadway, his musical-heavy resume included eight plays and a role as a jester in “Once Upon a Mattress,” which opened in 1959 starring Carol Burnett.

His nearly 20 movie roles encompassed two 1953 musicals, “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” with Marilyn Monroe and “The Band Wagon” with Cyd Charisse.

Over three decades, Mattox choreographed almost 30 ballets.

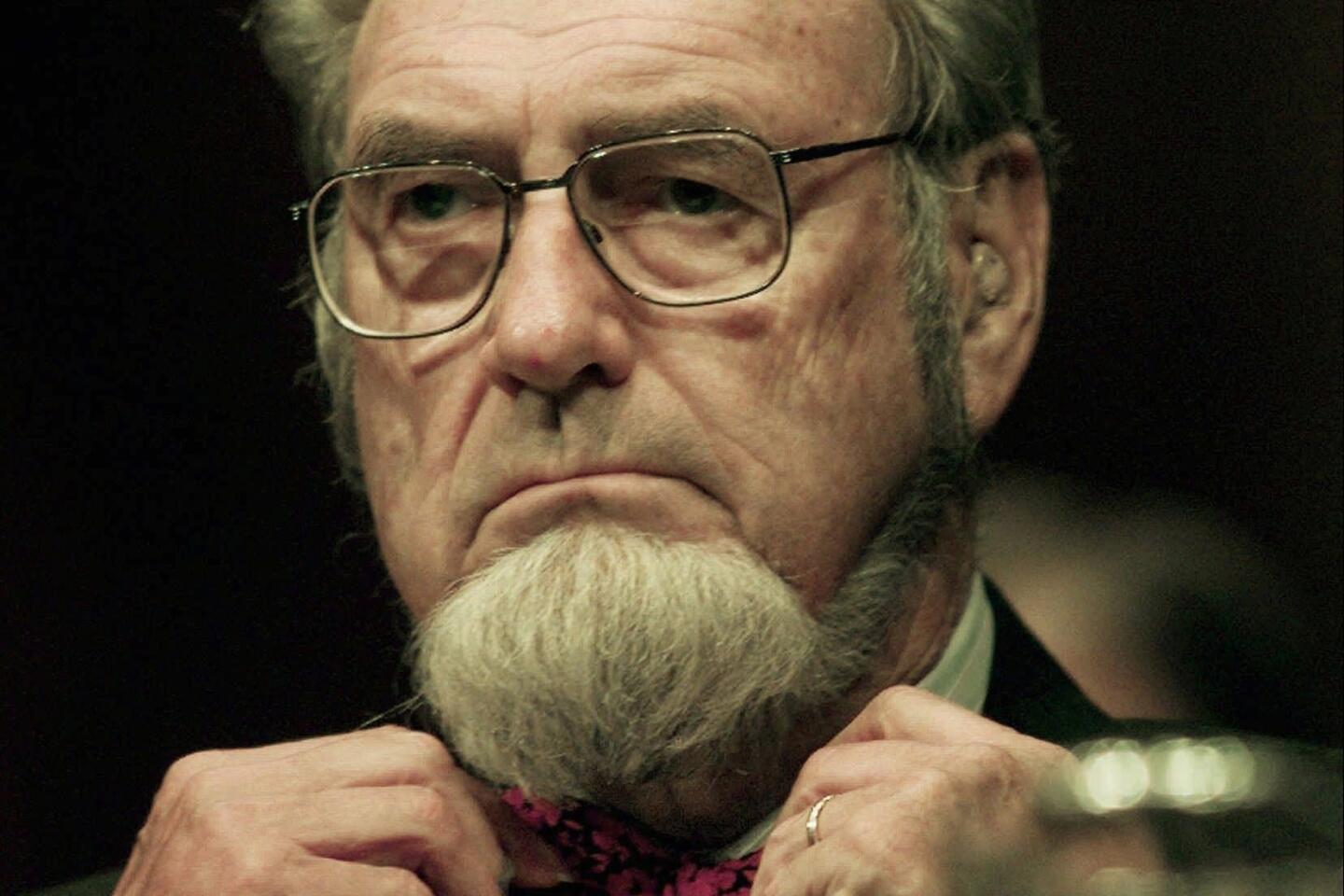

His ballet background made him “one of the five best dancers in the U.S.” as of the early 1950s, Kidd said in 1980 in the Monitor. (He died in 2007).

Noted choreographer Jerome Robbins seconded that assessment, according to Boross.

Saddened and embittered by marital difficulties, he moved to London to pursue his art, he told The Times in 1984. Twice divorced, he had three children with his first wife, three with his second and another from a relationship.

Survivors include his third wife, Martine Limeul Mattox, a dancer whom he met in London in the 1970s.

On the set of “Seven Brides” he pushed for perfection, doing scenes over and over even though Kidd saw little wrong with them. Mattox was equally demanding of students, whom he taught until he was almost 90.

Possessing a master teacher’s no-nonsense attitude, Mattox could sound a bit cranky: “Hey, don’t forget, at the end of each leg there’s a foot,” he snapped at a 1984 UCLA workshop. “Point it!”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.