Encyclopaedia Britannica ends print run

- Share via

By Robert Channick

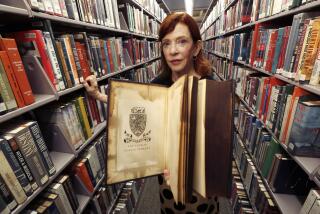

There have been more than 7 million sets of Encyclopaedia Britannica printed and sold over the years, an indispensable home reference library lining bookshelves, fueling dreams and salvaging homework assignments everywhere.

You can look it up. Online.

That’s because after 244 years, the Chicago-based company is shelving its venerable printed edition in favor of its Web-based version, completing a digital transition and marking the end of one of longest chapters in publishing history.

It’s a technological evolution, a cultural benchmark and, certainly, a moment in history.

“We just decided that it was better for the brand to focus on what really the future is all about,” said Jorge Cauz, Encyclopaedia Britannica’s president. “Our database is very large now, much larger than can fit in the printed edition. Our print set version is an abridged version of what we have online.”

In the days before the Internet, before television, before radio, before the United States was even a country, there was the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Neatly bound and brimming with facts, figures and illustrations, it was the authority on just about everything — a repository of all human knowledge distilled into alphabetized volumes and tucked on a shelf.

Founded in 1768 in Scotland, Britannica has been headquartered in Chicago since 1935, when it was under the ownership of Sears. Marketed door-to-door for generations, it was a robust business that employed thousands and sold more than 100,000 sets as recently as 1990, its best year ever, when it generated $650 million in revenue.

Within a few years, sales began to tumble, as consumers opted for home computers bundled with CD-ROM encyclopedias over the $1,500 leather-bound sets. More recently, the rise of high-speed Internet and Wikipedia shifted reference libraries online, with only a few thousand copies of the printed version trickling out each year to libraries, schools and a handful of neo-Luddite homeowners, according to Cauz.

The last run in 2010 produced about 12,000 sets of a new 32-volume copyright based on the 15th edition, a version that first rolled off the presses in 1974. There are about 4,000 sets left, selling for $1,395 each on the Britannica website. After they are gone, the iconic publication will be history.

“This is probably going to be a collector’s item,” Cauz said. “This is going to be as rare as the first edition, because the last print run of our last copyright was one of the smallest print runs.”

The beginning of the end for the print version came when Microsoft released Encarta in 1993, which impacted Britannica’s bottom line almost overnight. By 1994, print sales at Britannica had fallen to $453 million, and the company struggled to adapt to fast-evolving digital platforms.

With sales plummeting and profits gone, Britannica’s owner, the Benton Foundation, sold the encyclopedia operation to Swiss investor Jacob Safra in late 1995. By spring 1996, the company abruptly ended the door-to-door sales operation, cutting loose about 2,500 contract sales people worldwide, according to Cauz.

“Every single household would be contacted at least twice a year via an advertisement on TV or in the newspaper to get lead generations that then would be passed along to the salespeople,” Cauz said. “It was a very large and inefficient way of selling information.”

Shedding salespeople and looking for online success did not produce immediate results. Various strategies failed to right the company until the focus shifted from consumer sales to the $10 billion U.S. educational market about eight years ago.

The privately held company doesn’t disclose financial information, but Cauz says Britannica has been operating in the black since he became president in 2004, when he accelerated the digitization and diversification of the company. Only 15% of revenue now comes from the encyclopedia, with the bulk of income derived from the sale of instructional materials to schools.

About 500,000 subscribers pay $70 per year for full online access to Encyclopaedia Britannica. Cauz says that focusing on its digital products will help Britannica compete against Wikipedia, a free encyclopedia website built and maintained by users, which went online in 2001 and dominates the digital-reference space. During one recent week, Wikipedia received more than 86 million U.S. visits, compared with about 455,000 for Britannica.com, a trend driven as much by search engine algorithms as economics, according to Cauz.

“We know we have a challenge there,” Cauz said. “The challenge is not of preference. The challenge is of distribution and how to please an algorithm that tries to identify quality, but doesn’t really quite get it right all the time.”

Britannica opened its articles to user contributions three years ago. Unlike Wikipedia, however, Britannica fact checkers fully vet every entry thoroughly and quickly, making its online database more reliable than a user-generated source.

About 30% of Britannica’s content is available at no cost through search engines. Hoping to drive more traffic to its site, the full database is now accessible for a one-week free trial. Although the online encyclopedia is not the primary focus of Britannica, Cauz is looking to monetize increased site visits with more online ad revenue while converting casual users into subscribers.

Although some may bemoan the loss of the print version, Britannica’s very survival is an accomplishment following a digital revolution that spelled the end for more than a few reference publishers. Among the casualties were Funk and Wagnalls and Collier’s Encyclopedia, both of which ceased publication in the late ‘90s. Encarta itself was discontinued in 2009 as Wikipedia and other online reference sources rendered the onetime category killer all but obsolete.

One of the few print encyclopedias left standing is World Book, a 95-year-old Chicago-based company that is still selling its 22-volume 2012 edition for $1,077 on its website.

The economic advantages to digitizing reference works are overwhelming, but they may come with a cost.

“There’s always something gained and lost when something becomes digitized,” said Matthew Kirschenbaum, associate professor of English at the University of Maryland who specializes in digital humanities and electronic publishing.

Kirschenbaum points out that the serendipitous discoveries that come from flipping through a book may be lost online, for example.

“There is no such thing as simply a kind of seamless, transparent translation from one medium to another,” Kirschenbaum said. “There’s always going to be a role for the physical form that the medium takes in terms of how the thing is used, and how it’s received and understood.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.