Winter’s snow is disrupting the Sierra Nevada’s summer

- Share via

Even when snowbound and inaccessible to vehicles, the rustic Tioga Pass Resort on the crest of the Sierra Nevada range offered homemade pie, a wood-burning stove and plump sofas to relax on after a day of backcountry skiing.

But the winter of 2017 was more than the log cabin lodge, just two miles east of

Trails, roads and campgrounds throughout the Sierra high country were hit hard by snow and runoff from one of the largest snowpacks in recorded history, leaving public agencies scrambling and summer visitors feeling lost. At Tioga Pass Lodge, established in 1914, loyalists’ hopes of kicking back on a sunny afternoon have taken a particularly tough wallop.

Entombed in 20 feet of hard pack known as “Sierra cement,” the lodge “suffered severe crunch injuries,” said Dave Levy, manager of the resort, which is owned by a consortium of investors.

A team led by Levy used shovels to dig down through the snow to reach the kitchen door. Sheared structural support beams appeared like ghostly shadows in the glare of a flashlight.

“Inside, the bad news was much worse,” he said. “Doors won’t open, windows are shattered, floors are warped, the roof sags. We may reopen sometime next year, but it won’t be easy fixing a place built like a jigsaw puzzle with antiquated construction techniques.”

A creek running through the property leased from the U.S. Forest Service is surging over its banks with snowmelt, undermining the foundations of the lodge and several cabins surrounding it.

Over the July 4 weekend, as thousands of summer vacationers streamed into the mountains with coolers, bicycles, fly rods and barbecues, the runoff in streams peaked.

But with many popular trails and campgrounds still closed because of safety and health concerns, rangers struggle to keep up with visitors arriving each day with the question: “Where can we find a place to camp?”

The hard recovery ahead

“Nearly every campground in the area has problems,” said Deb Schweizer, a spokeswoman for the Inyo National Forest. “There are broken water systems and sewer lines, gates that bent under the weight of so much snow, washed-out bridges and trails, damaged roads, fallen trees, downed power lines.

“It’s taken an incredible amount of cooperative efforts by multiple agencies to open as many campground facilities and roads as possible — and we’re opening more every day,” she said.

In the meantime, the Forest Service has been promoting its “dispersed camping” rules, which allow visitors to pitch a tent on certain undeveloped forest lands. This strategy has brought only despair to Dwayne Beaver, leader of the volunteer fire department in Lee Vining, about 10 miles west of the Tioga Pass.

“It’s costing our fire department money — and lots of lost sleep,” he said. “That’s because whenever someone needs a rescue, or inexperienced campers build an unauthorized fire in a ring of rocks, we have to scramble to deal with it.”

Signs of the snowpack-fueled deluge are visible in most of the watersheds draining the Sierra Nevada. Smallmouth bass and other fish, for example, were found floating belly-up in a stretch of the Lower Owens River near the town of Lone Pine — suffocated by mud and debris flows, the

But Southern California Edison and the DWP, which operate extensive networks of dams, diversions and hydroelectric plants across the Sierra range, say that things are not as bad as they could have been.

With snowpack levels at 241% of normal, Los Angeles Mayor

Preparing for the worst, engineers and heavy-equipment operators worked furiously to empty reservoirs and clean out ditches and pipelines to keep them from being overwhelmed by flooding.

On Thursday, SCE officials launched a helicopter to survey three century-old reservoirs operating under water-level restrictions that state and federal regulators had required in part because the area is prone to earthquakes.

The reservoirs — Agnew Lake, Gem Lake and Waugh Lake — are used to store water and generate power at the SCE’s Rush Creek Hydroelectric Project near the town of June Lake.

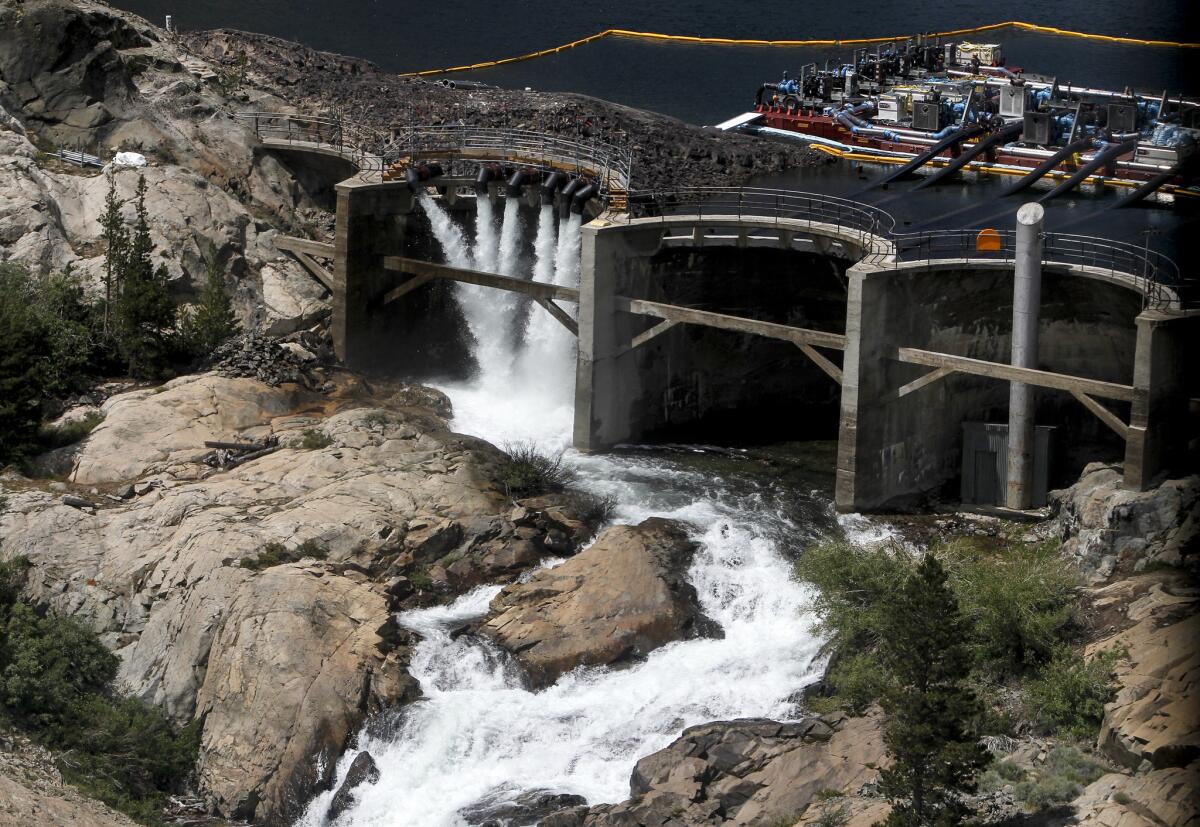

From 1,000 feet above Agnew Lake, elevation 8,500 feet above sea level, 12 massive water pumps were clearly visible, sending torrents of snowmelt over the spillway and into Rush Creek, one of Mono Lake’s major tributaries. Heavy-duty helicopters had flown them in, engineers had assembled them and the utility officials now were pleased to see them working smoothly.

“It took two weeks to design that pumping system and another six weeks to build it,” said Terry Maddox, an SCE energy systems engineer. “It handled the peak flows of snowmelt, and now the worst is over.”

As a precaution, however, the Inyo National Forest has closed nearby hiking trails through Sept. 1, warning that higher-than-normal water levels make the reservoirs especially vulnerable to seismic activity.

The costs of the unprecedented efforts to counter the threat of destructive flooding this year are expected to be passed on to rate payers, officials for the DWP and Southern California Edison said.

Moths the size of hummingbirds

The wet winter added 2 1/2 feet of water to Mono Lake, nesting grounds for thousands of California gulls, and it transformed the surrounding meadowlands into wildflower panoramas.

Nora Livingston, 27, a naturalist with the nonprofit Mono Lake Committee, has been revising her guided tours to highlight new natural wonders that seem to crop up daily.

Bringing her Subaru to a stop along a dirt road near Lower Horse Meadows, Livingston said, “Follow me. I want to show you something truly amazing.”

Moments later, she was striding along a meandering wetlands edged with sage that had been bone-dry for years. Now, yellow seep monkey flowers blossomed in a half-mile-long swath.

With the flowers have come swarms of Western tiger swallowtail butterflies and Sphinx moths the size of hummingbirds. Birds such as lazuli buntings and mountain bluebirds feast on the insects attracted to the flowers.

Reaching out as if to embrace the vista, Livingston said, “This would not have happened without all that snow and high water on the mountains.”

ALSO

After the drought, the 'Killer Kern' river is a different beast

The Kings River flooded from snowmelt that couldn't be measured or predicted

Skiers hit the slopes in bikini tops as California's endless winter endures a heat wave

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.