Tiny coqui frog becomes a big problem in Hawaii

- Share via

Reporting from Hilo, Hawaii — There’s a different kind of neighborhood watch on duty in Puuloa, a small rural subdivision on Hawaii’s Big Island. Wearing headlamps and armed with hand sprayers filled with citric acid, Daniel Montgomery and his neighbors creep through backyards listening for the intruder’s distinctive call:

“Ko Keee ... Ko KEEE.”

The coqui frog has infested large swaths of the Big Island, with more than 10,000 per acre in the worst-hit areas.

The frogs’ high-pitched nighttime mating calls have caused residents many sleepless nights. But a few communities have managed to stay coqui-free, and Montgomery and his two dozen neighbors are determined to keep the coqui at bay.

“It’s like a neighborhood coqui watch,” Montgomery said. “We all know each other, and we all have a significant stake in our properties. Once you have a coqui on one person’s property you can be sure it’s going to lay eggs, and soon it will be everyone’s issue.”

The quarter-sized frog has become an outsize problem for Hawaii.

Originally from Puerto Rico, the coquis that colonized the Big Island are believed to have hitched a ride on some potted plants from Florida in the 1990s.

With no snakes, tarantulas or other natural predators to curb the population, the frogs proliferated, and state officials fear the little gray-brown amphibians will upset Hawaii’s delicate ecosystems by devouring insects vital to pollination. Officials also worry the frog could harm export plant sales.

Then there’s the sound.

In Puerto Rico, the coqui’s call is likened to sweet music and is celebrated in poetry, literature and song. But to the Hawaii Invasive Species Council, a state agency, their vast numbers create a “loud, incessant and annoying call from dusk to dawn.” The male frogs chirp at about 90 decibels, roughly as loud as a lawn mower or garbage disposal.

The density of coquis in the Aloha State is three times greater than in Puerto Rico. There are so many frogs that larger ones have taken to eating smaller ones, though cannibalism won’t be enough to keep their numbers in check.

Hawaii and the federal government have spent millions on control and remediation efforts since the frogs first arrived. This year, Hawaii lawmakers considered making it a felony to transport a coqui, even unintentionally. The bill was tabled.

Researchers have posited all sorts of ideas for containment. University of Hawaii entomologist Arnold Hara tested a caffeine spray that gave the frogs heart attacks and has proposed releasing masses of male frogs sterilized through irradiation into the wild.

“As far as eradication, it’s impossible on the Big Island,” Hara said. “We’re focusing on containment and preventing the spread of coqui to other islands.”

Early on, Hara figured out that spraying plants and flowers with scalding water for five minutes kills coqui hitchhikers and their eggs. More recently, he developed a cold technique for plants too delicate for the heat, such as chrysanthemums. Two days in 38-degree refrigeration does the trick. Citric acid is the most common and effective spray, but it can burn plants.

Nurseries throughout the Big Island use Hara’s methods when exporting plant material to the other Hawaiian islands or California. Even container ship and dock workers are trained to listen for coquis and call state frog catchers if they suspect a shipment is contaminated.

Despite the precautions, coquis still turn up on other islands. Unlike most frogs, coquis lay their eggs not in water but on plants. The tadpoles mature in the eggs and emerge as quarter-inch-long froglets.

Maui has one infestation in a steep gulch that’s been tough to treat.

On Oahu, Keevin Minami, a land vertebrate specialist with the Hawaii Department of Agriculture in Honolulu, recently spent several evenings listening to frogs near Kaneohe. Minami, dubbed the frog whisperer by local media for his uncanny ability to mimic coqui calls, estimates that he’s caught nearly 100 frogs on Oahu this year. That’s up from 30 frogs in 2013 and 66 frogs in 2012. Still, despite the large catch, he said the frogs are far from establishing themselves on the island.

“So far we have 100% containment,” he said. “They’ve managed to come, but we’ve managed to eradicate them. There aren’t many species we can completely get rid of, but this seems to be one.”

Minami relies on the public to report the coqui. He encourages people to record the sound with their cellphone so he can confirm it’s not a bird or a greenhouse frog, whose chirp is much shorter and softer. He and a colleague then visit sites after dark and listen for the coqui’s distinctive two-tone call.

“It’s essentially hunting, but hunting something the size of a quarter in an area the size of a football field,” said Jonathan Ho, a state plant quarantine inspector and expert frog catcher.

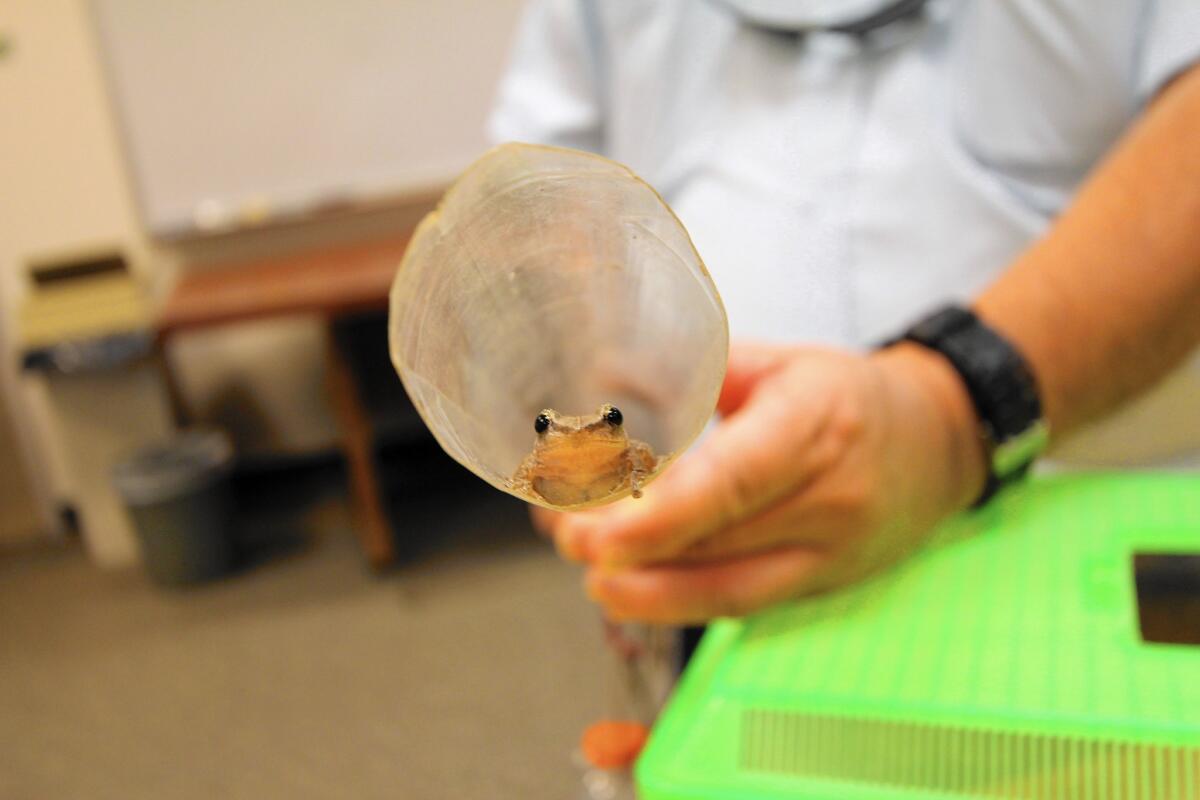

Once a frog is spotted, Ho covers it with a coqui “wand” — a homemade trap of transparent plastic tubing roughly the size of a florescent light bulb. The frog then jumps up into the tube and sticks to the sides like a lizard.

But coqui wands can’t make much of a dent in the population on the Big Island.

In Puuloa, a community in south Kona, residents say the neighborhood coqui watch came together after a nursery set up shop at the front of the subdivision seven years ago.

On rainy nights, Montgomery said, he can hear the chorus of hundreds of frogs at the nursery, about a mile away from his house. Every now and then he’ll catch one or two in his backyard. He and his neighbors participate in a county-run voucher program to buy citric acid, which is otherwise pricey.

For big jobs, they borrow a 150-gallon sprayer from the county that can reach up to 300 feet. Montgomery said the residents are working with the nursery owner and the landowner to come up with an eradication plan.

“It used to be that you’d hear birds up until 5 p.m., they’d go to sleep and then you’d hear nothing,” Montgomery said. “The community really came together because we understand the impact. We don’t want anyone to lose their peace and quiet.”

Follow this link to hear the ko-KEEE.

Lin is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.