China leaders’ summer retreat to Beidaihe shrouded in secrecy

- Share via

BEIDAIHE, China — Celebrity sightings used to be part of the fun in Beidaihe, the summertime retreat of the Chinese Communist Party.

“In the old days, people would see Mao Tse-tung or Zhou Enlai walking around, shopping, eating in a restaurant, talking to ordinary people,” said Yu Heping, 62, a lifelong resident who used to farm corn and sorghum and now works in the tourism industry.

Nowadays, the presence of the Chinese leadership is viewed primarily in fleeting shadows through tinted glass, as their black Audis glide past stifling security roadblocks. The leaders remain secluded in their enclave, with their own beaches, their own restaurants and their own gardeners and cleaners who come from Beijing. Locals are rarely hired or admitted into the compound.

“We never see them nowadays — only see their motorcades,” said Yu.

It is just another sign of the isolated and secretive nature of the Chinese leadership, ever opaque in its policymaking, even as it has sought to convey a more open and welcoming appearance.

The Chinese hierarchy is well aware that Beidaihe can convey an impression of elitism. In 2003, President Hu Jintao canceled the retreat, in part a public relations ploy to show that the leadership was giving up its perks and in part to minimize the meddling of his predecessor, Jiang Zemin, who thrived in Beidaihe’s smoky, backroom ambience. Later, the tradition resumed; the party elders simply feeling a need to decamp somewhere away from the prying eyes of Beijing.

These days, who is coming and going at Beidaihe, along with the weightiest matters of governance, is a state secret.

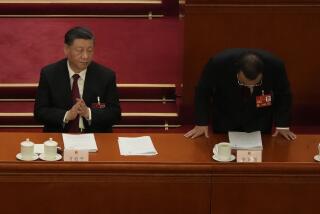

All that has been released so far from the annual retreat was an Aug. 5 dispatch on the state news service saying that Xi Jinping, the vice president and heir apparent, had met with 62 leading educators, artists, workers, rural medical staff and astronauts and “encouraged them to contribute more to the country’s development.”

In truth, political analysts believe this summer’s session has been devoted to hashing out the roster of who will rule the world’s most populous country for the next decade. It is a critical transition, with most of the leadership retiring and the party reeling from the downfall of Bo Xilai, the ex-Politburo member whose wife went on trial last week in the murder of an Englishman.

The new leadership will be formally anointed at the 18th party congress scheduled to take place in October; the exact date is itself a state secret.

If anything, says Jin Zhong, a veteran political journalist working out of Hong Kong, the Chinese leadership is revealing less and less these days about the inner workings of the political process.

“At times, I think they are going backwards,” Jin said.

To critics, Beidaihe epitomizes the Communist Party’s ongoing lack of transparency. As if the regular scheduled meetings, the upcoming 18th congress of the Communist Party and a plenum just before were not secretive enough already, the leaders departed Beijing for the extra layer of isolation provided by Beidaihe.

“This is a tradition in authoritarian regimes. Stalin did the same in his old age — invite people to his villas to drink and dance and make the key decisions,” said Jin.

Political analysts say the Beidaihe sessions are about divvying up power, position and patronage.

“There is no systematic or mechanism about who becomes a Politburo member. It’s not in the party’s rules. They have to talk it out,” said Li Datong, a former editor of China Youth Daily, whose father, an official of the Communist Youth League, used to have a villa in Beidaihe.

Li says he heard from good sources that during the summer of 2007 in Beidaihe, the party elders held an informal poll and tapped Xi and Li Keqiang, the vice president and vice premier, respectively, to replace Hu and Premier Wen Jiabao in this year’s transition. But they didn’t pick the members of the 25-strong Politburo or the Standing Committee (now nine members), necessitating another powwow in Beidaihe this year.

Beidaihe lies 180 miles to the east along a bay of the Yellow Sea known as the Bohai Sea. Although the beaches are gravelly, the waters a turbid gray, the landscape is lush with cypress groves and wildflowers, and the location as close as Beijing gets to the sea.

In the 19th century, foreign residents of China began building vacation villas here, and after the Communist Party came to power in 1949, the housing was confiscated. New ones have been constructed in the same style — concrete buildings with red roofs and rounded verandas facing the sea — so that each Politburo member would have his own.

The summer sessions were convened by Mao, who loved to swim and was often photographed frolicking in the water. The tradition was suspended during the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, and the peasants around Beidaihe traipsed through the enclave to gawk at the appurtenances of privilege.

“That’s the only time any of the people from this town have been inside,” Yu said.

Beidaihe feels like something of an anachronism today, an ode to a long-gone era. At intersections, crisply dressed traffic police officers, many of them attractive young women in aviator shades, direct the vehicles with elaborate hand motions like in North Korea. There are also resorts with names like the Coal Miners Sanitarium, the Railroad Workers Sanitarium, built in the 1950s as retreats to reward “outstanding workers.”

But these days, most Chinese no longer go on vacation with their co-workers, so the rooms are packed with Russian tourists who buy 10-day packages for as little as $800 and jam into the short stretch of public beach between the leadership compound and a beach assigned to the People’s Liberation Army.

There is a strange juxtaposition of the frivolity of summer — the inflatable crocodile rafts, the bright plastic tubes for the many Chinese who can’t swim, the silly hats and sunglasses — and the oppressive security. Motorists go through multiple checkpoints on their way to the resort and police stand on every corner. Wire fences run from the water to the beach to keep the penned-in tourists from wandering.

“This part is for us, the common people,” said an older Chinese man in a swimsuit, gazing from the public beach across the fence into the nearly empty leadership beach where a girl was playing alone with a pail in the sand. “That’s for them.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.