Guatemala full of questions after genocide conviction annulled

- Share via

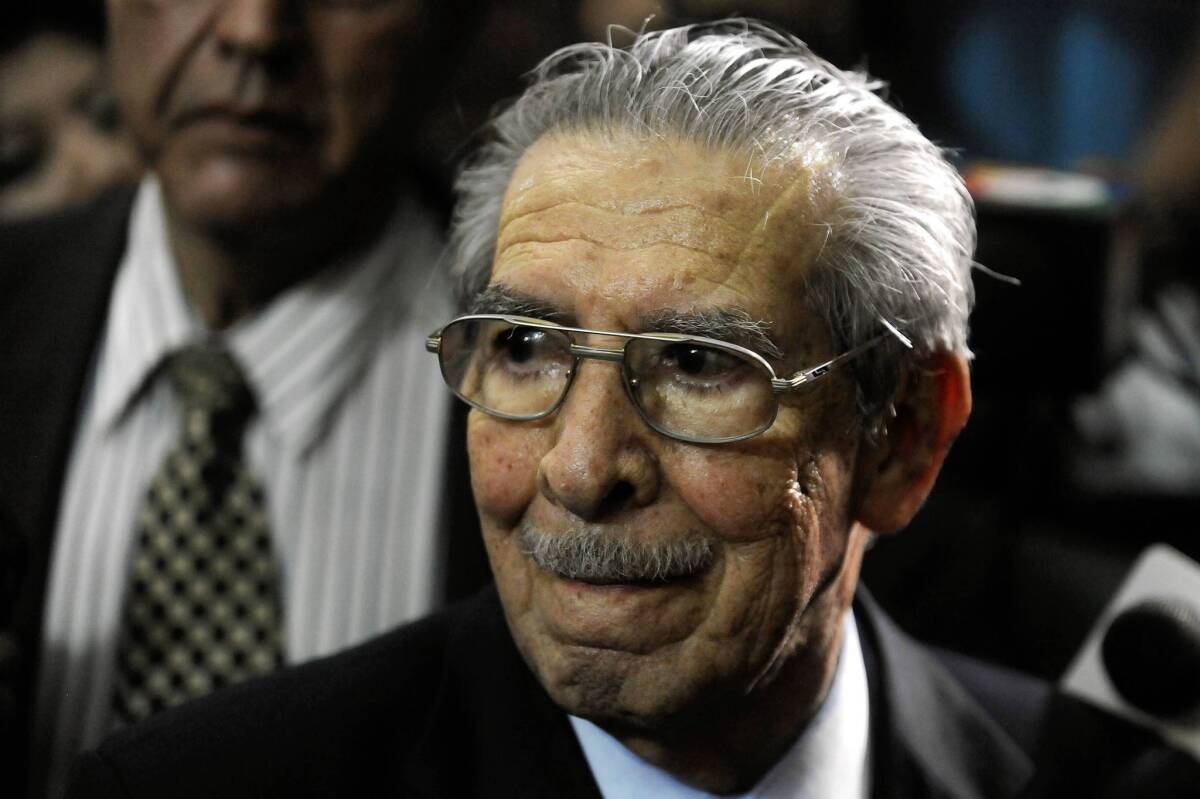

MEXICO CITY — The Guatemalan high court’s decision to annul the genocide conviction of former military dictator Efrain Rios Montt on Tuesday revived questions about his responsibility for the slaughter of some 1,700 ethnic Maya people.

The ruling late Monday, which voided Rios Montt’s May 10 conviction, also raises questions about the kind of retrial he might have and about a judicial system that has long been considered weak, corrupt, prone to impunity and susceptible to pressure from powerful outside forces.

Rios Montt was Guatemala’s ruler for 17 months in 1982 and 1983, one of the bloodiest periods of a multi-decade civil war that pitted Marxist guerrillas against conservative government forces. His dramatic two-month trial focused on the massacre and displacement of thousands of indigenous people in the mountainous Ixil region during that era at the hands of government troops and their supporters.

The three-judge panel that found Rios Montt guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity also sentenced him to 80 years in prison. Its decision was cheered by liberals and a number of international human rights groups who described it as an example of a Guatemalan court system capable of doing the right thing.

“The conviction of Rios Montt sends a powerful message to Guatemala and the world that nobody, not even a former head of state, is above the law when it comes to committing genocide,” Jose Miguel Vivanco, Americas director at Human Rights Watch, said in a statement shortly after the verdict. “Without the persistence and bravery of each participant in this effort — the victims, prosecutors, judges and civil society organizations — this landmark decision would have been inconceivable.”

But Monday’s 3-2 decision by the Constitutional Court calls on the trial court to rehear the case from the point at which it stood April 19. The three high court judges who voided the conviction essentially supported lower court rulings that Rios Montt was denied his due process rights when the judges who convicted him briefly ejected his attorney from the courtroom, leaving his defense to a co-defendant’s lawyer for several hours.

It’s also possible the trial will have to begin from scratch, Arturo Aguilar, a spokesman for the attorney general’s office, said in an email Tuesday.

Aguilar said prosecutors planned to challenge the high court ruling. If they are unsuccessful, the original judges may have to recuse themselves from the case because they have already issued a ruling against Rios Montt, and that would mean a new trial, he said.

Many of the prosecution witnesses during the trial were Ixil Maya who traveled from the remote countryside to Guatemala City to tell horrific stories of torture and killing by government forces.

Aguilar said that requiring such witnesses to testify again would amount to “a re-victimization of the victims.”

“It’s a spectacular logistical challenge. And we will have to confront the challenge of determining which victims and witnesses want to come back to participate,” he said.

Some analysts wondered whether the wealthiest and most powerful forces in Guatemala were manipulating the system.

“The method of avoiding justice in Guatemala has never been exclusively by the use of illegal force,” said Douglass Cassel, a Notre Dame law professor and human rights law expert who has represented victims of Guatemalan violence in the Organization of American States’ inter-American human rights justice system. “The legal systems in many Latin American countries in general, and in Guatemala in particular, for decades have been skewed in favor of the powerful and against the weak.

“In this case, in a very general way, you had enough forces to get a case going and carry it through, but they were up against very well-resourced Guatemalan lawyers who know how to work the system in support of their client.”

Some of Guatemala’s most powerful public voices have criticized the case and the conviction, including the country’s national business council. President Otto Perez Molina, who commanded troops in the area where the massacres occurred, has said that genocide did not occur during the civil war.

Some of Rios Montt’s supporters have contended that the trial was an attempt by the Guatemalan left to seek vengeance against the country’s conservatives.

An editorial in the national newspaper Prensa Libre noted that the high court’s ruling should be viewed as neither a “victory nor a defeat,” but rather an example of the Guatemalan courts defending the rights of the accused.

“The legal battle will resume,” the editorial said, “and it is hoped that the participants … will act without being shown to be partial.”

Cecilia Sanchez of The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.