Key Italian crime suspect held in Spain

- Share via

MADRID — Neapolitan gangsters, including the alleged fugitive boss captured Saturday night in the city of Marbella, have a name for Spain: La Costa Nostra, or Our Coast.

The term plays off Cosa Nostra, or Our Thing, as the mafia is called, and underscores what authorities say: that Spain has become a top foreign base for the Naples underworld, the Camorra, in the last decade. Spanish police have arrested half a dozen suspected Neapolitan crime figures this year alone.

“They use that name Costa Nostra because it’s like a second homeland for them,” said Alessandro Pennasilico, an Italian prosecutor in Naples, in an interview. “They like Spain -- the climate, the coast, the beaches, because it’s close to their culture. And the Camorra goes where there is business. Spain is an important country regarding the trafficking of drugs.”

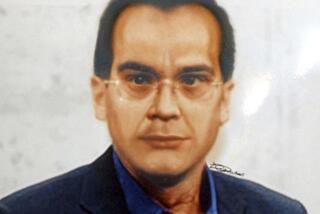

The nickname of purported boss Raffaele Amato is “the Spaniard.” He partied in Marbella, a beachfront refuge of high-rolling international desperadoes and dubious fortunes. Investigators say he set up multinational cocaine deals in Barcelona. Moving among Spanish hide-outs, he allegedly waged a long-distance war for the housing projects in Naples that are the heart of his empire. And he speaks Spanish like a native.

Amato’s capture Saturday was a major victory for Italian investigators. The balding 44-year-old gained notoriety for allegedly setting off a turf war with a rival clan between 2004 and 2007 that littered the high-rise slums of Naples with 70 bodies. The battle was retold in “Gomorra,” a book by journalist Roberto Saviano, and in the recent film of the same name.

The Camorra’s intense activity in Spain reveals evolving alliances and shifting global crime networks, investigators say. Starting about seven years ago, Amato was a key player in a number of decisive underworld sit-downs in Spain, the gateway for Latin American cocaine smuggled into Europe, said Antonio Laudati, a top official in Italy’s Justice Ministry and former chief prosecutor in Naples.

Europe became an increasingly hot market for cocaine because of rising demand, a strong currency and the hardening of U.S. borders after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Laudati said in a telephone interview. The Neapolitans met with Latin American and Spanish gangsters to build new partnerships and develop the European market, he said.

“They reorganized the routes,” Laudati said. “One important route for cocaine into Spain went through North Africa. Another crossed the Balkans into Italy. And Barcelona became a hub for a land route for cocaine to Italy through France, where the Marseilles underworld has always had close ties to the Camorra. So you had a mixed operational group of bosses base itself in Spain.”

The Camorra enlisted Spanish seagoing smugglers and front companies that concealed loads in shipments of products such as marble and seafood, Laudati said. Italian gangs also took advantage of the booms in real estate and construction in Spain to launder millions, according to authorities.

Although the Neapolitan crime clans are flashy and murderous at home, they avoided violence in Spain because it was seen as a place to do high-level business and lie low.

Nonetheless, the numerous arrests in Spain show that Spanish and Italian law enforcement have developed good cooperation. Amato was arrested in 2005 in Barcelona but was later released because of a judicial error in which the deadline for his prosecution passed by a day.

Police began tracking him again in 2006. He lived in southern Spain and used fake Spanish documents to travel to see his family at upscale hotels in London, Tokyo and Turkey, according to Italian authorities and media reports.

Last weekend, surveillance and wiretaps paid off when Italian and Spanish police trailed Amato on a 30-mile drive along the Mediterranean from Malaga. They arrested him on his way to a Saturday night date in Marbella, the glitzy capital of “his coast.”

--

Special correspondent Maria de Cristofaro in Rome contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.