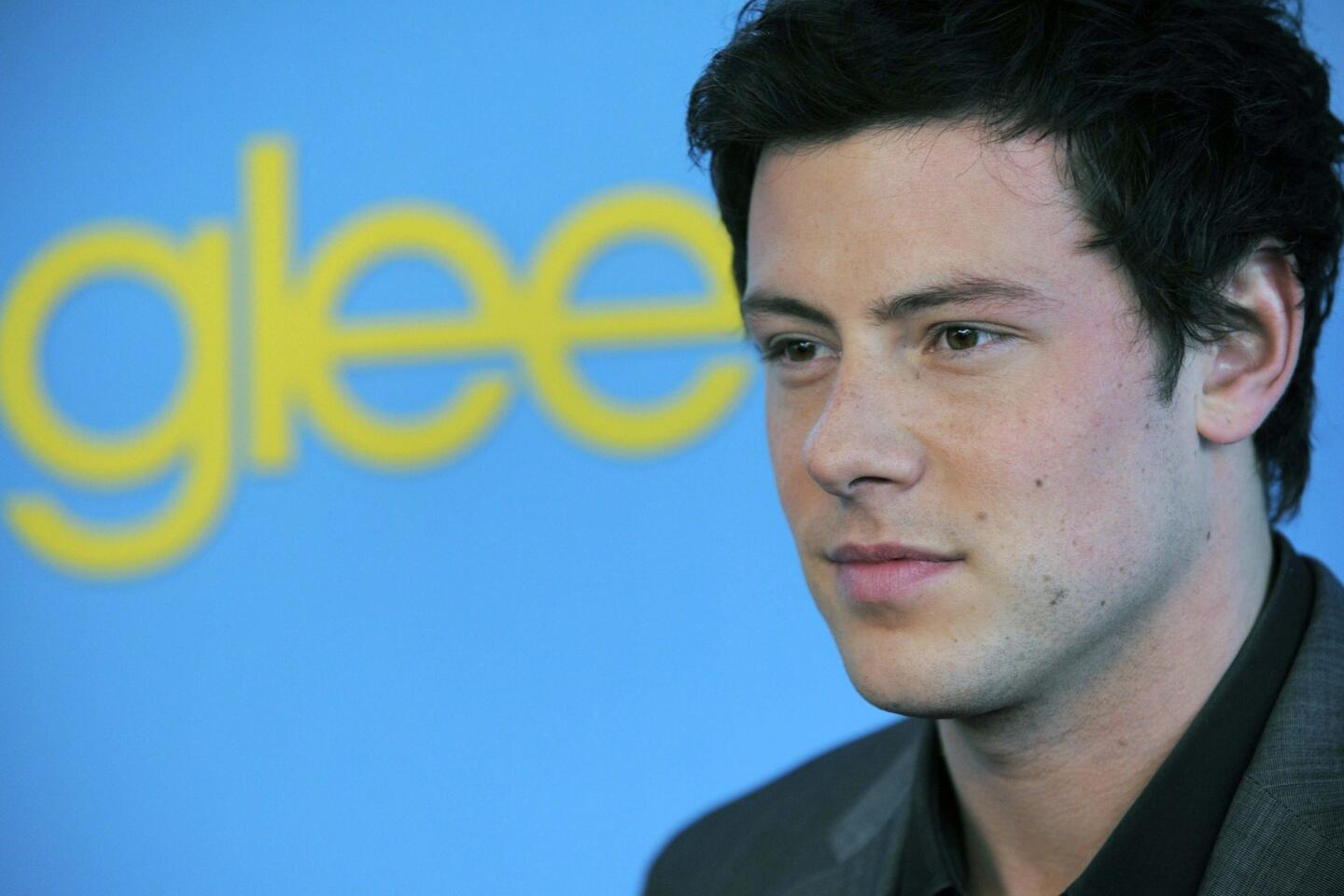

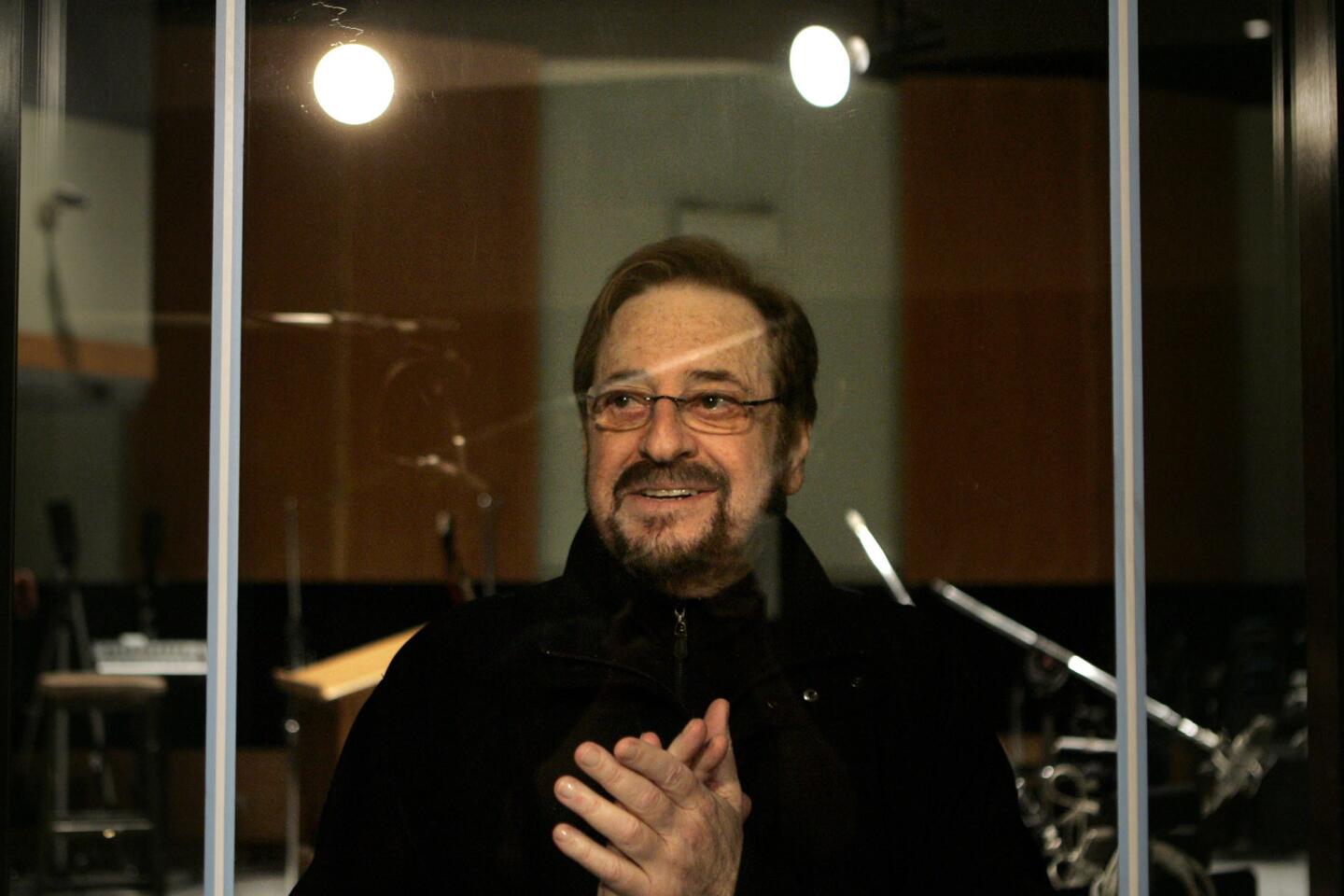

Father Maur van Doorslaer dies at 87; famed for folksy plaques

- Share via

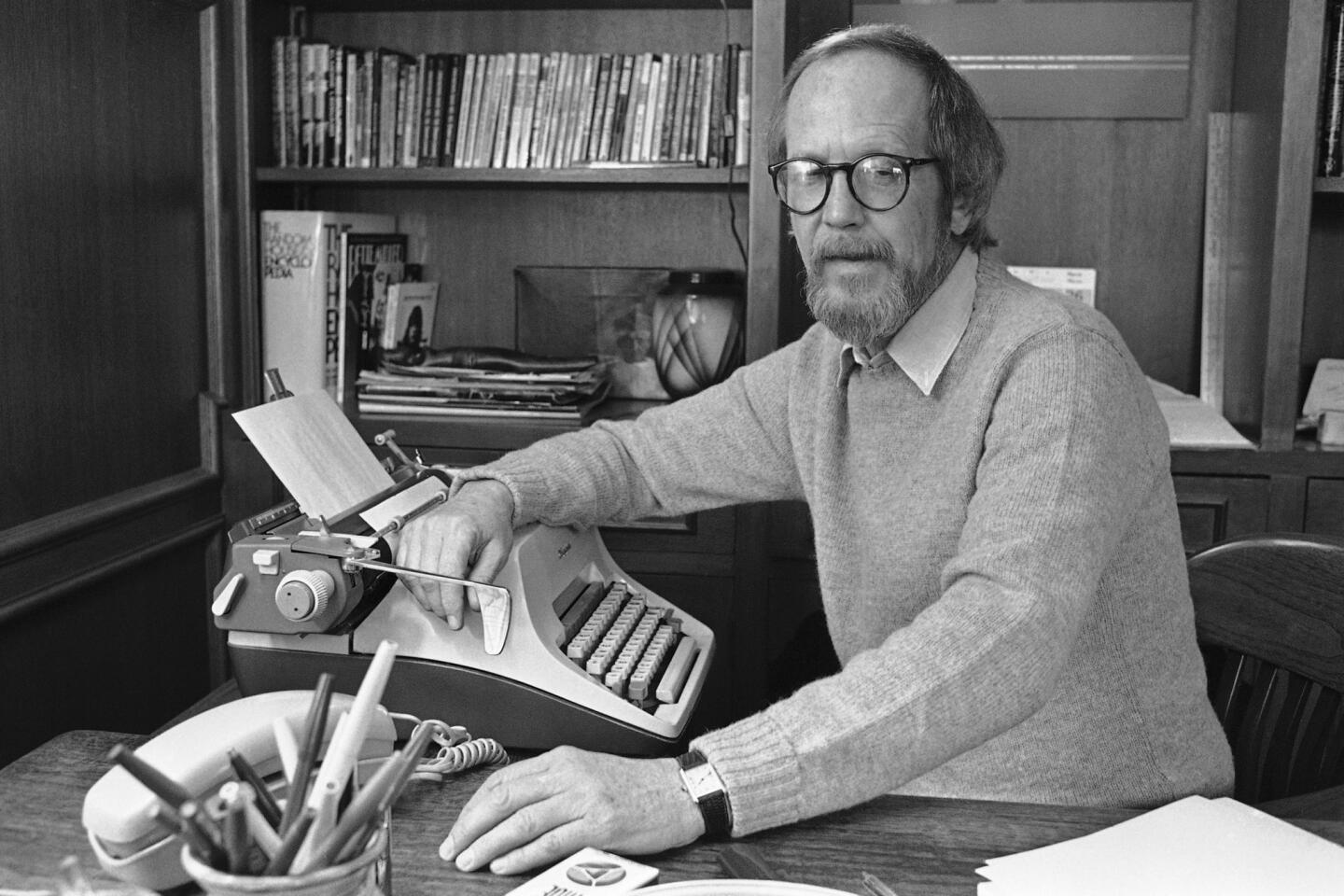

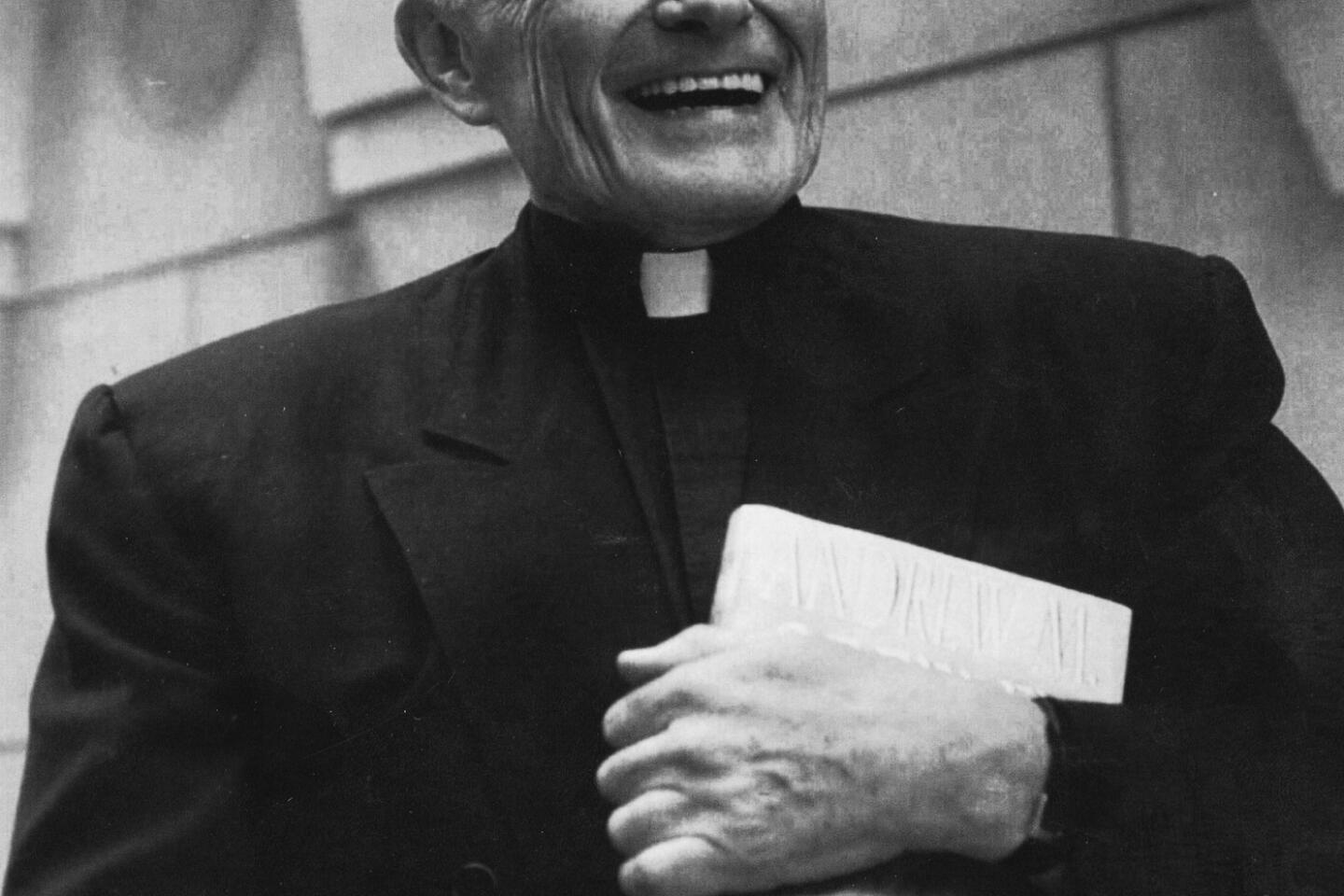

Father Maur van Doorslaer lived a kind of double life.

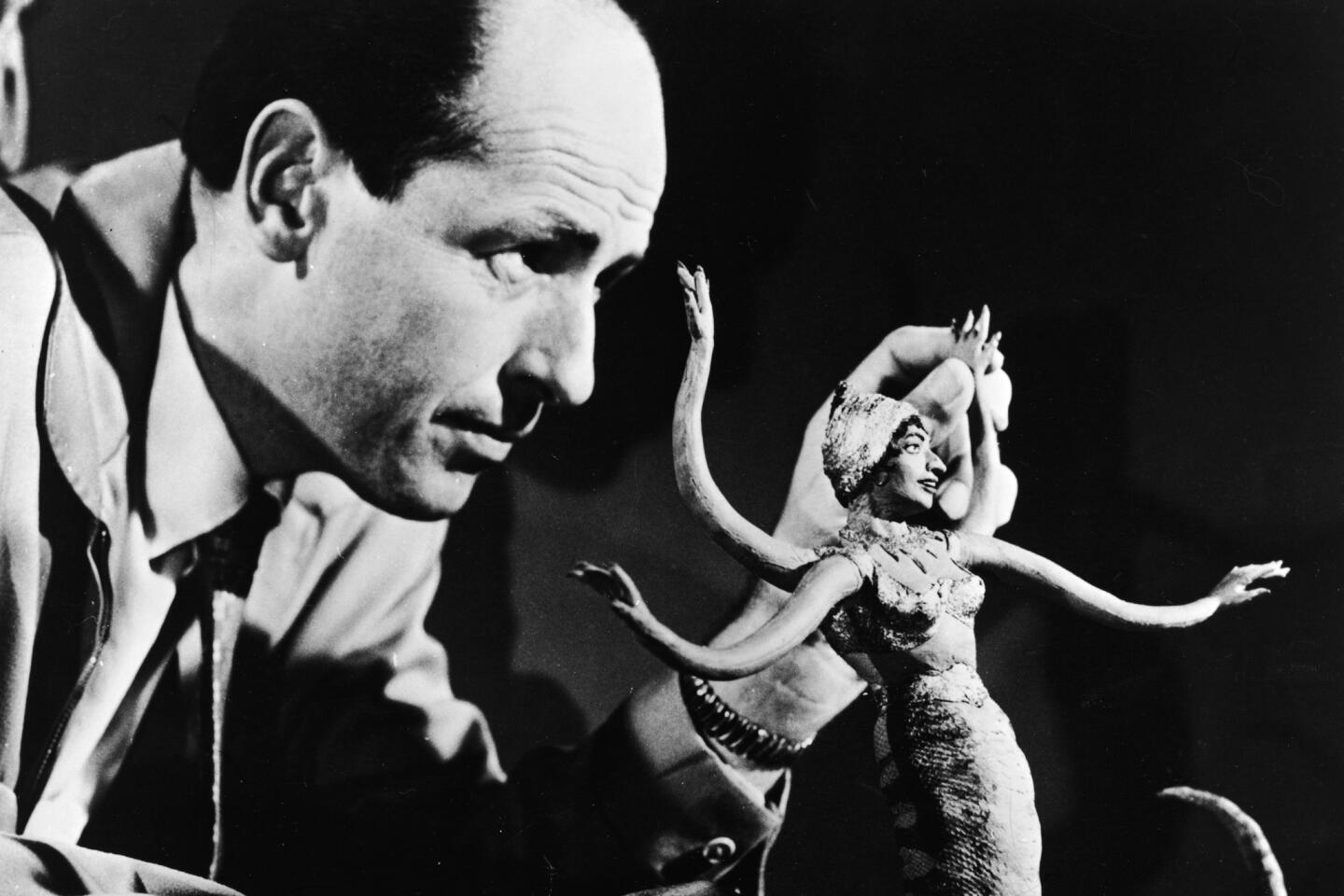

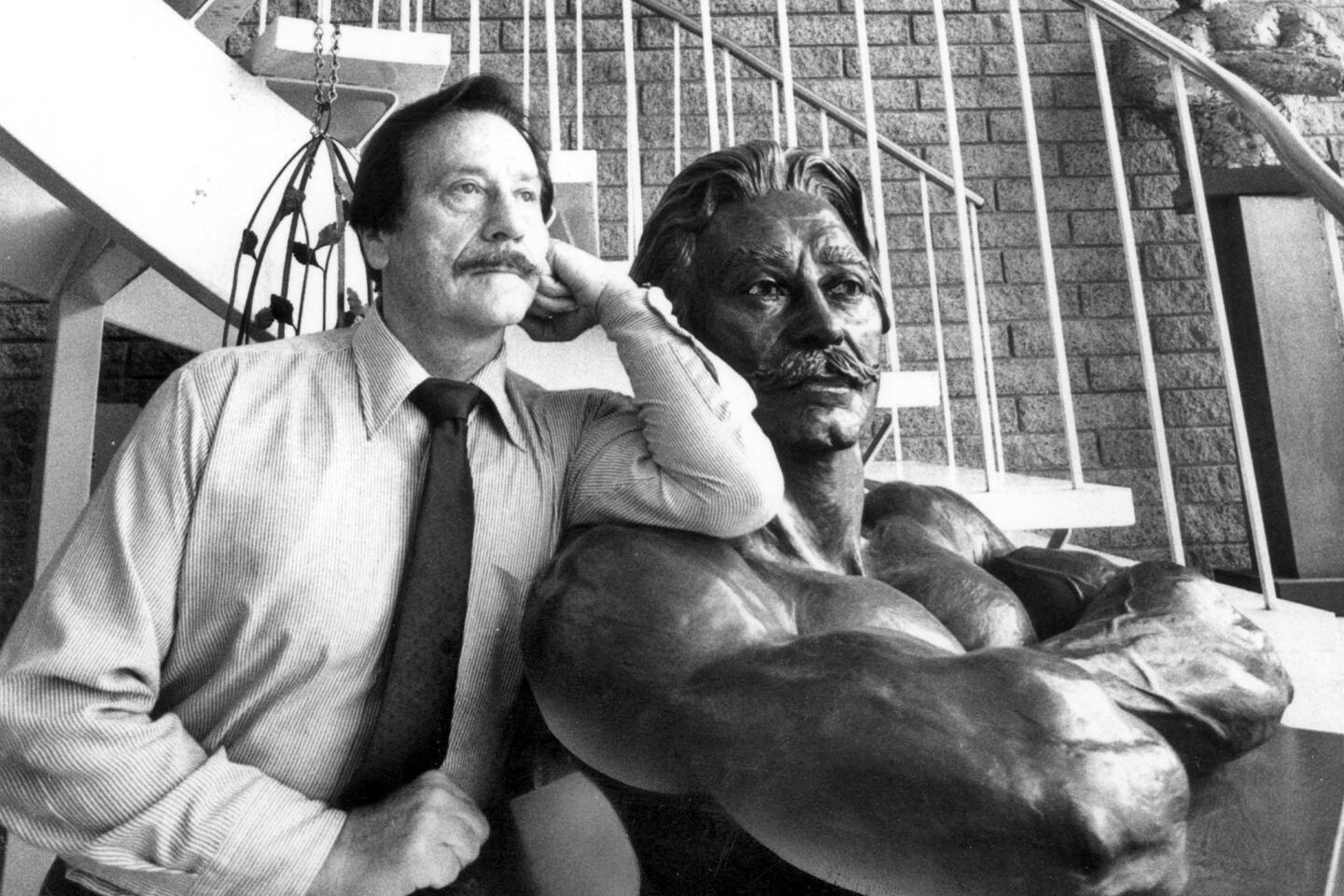

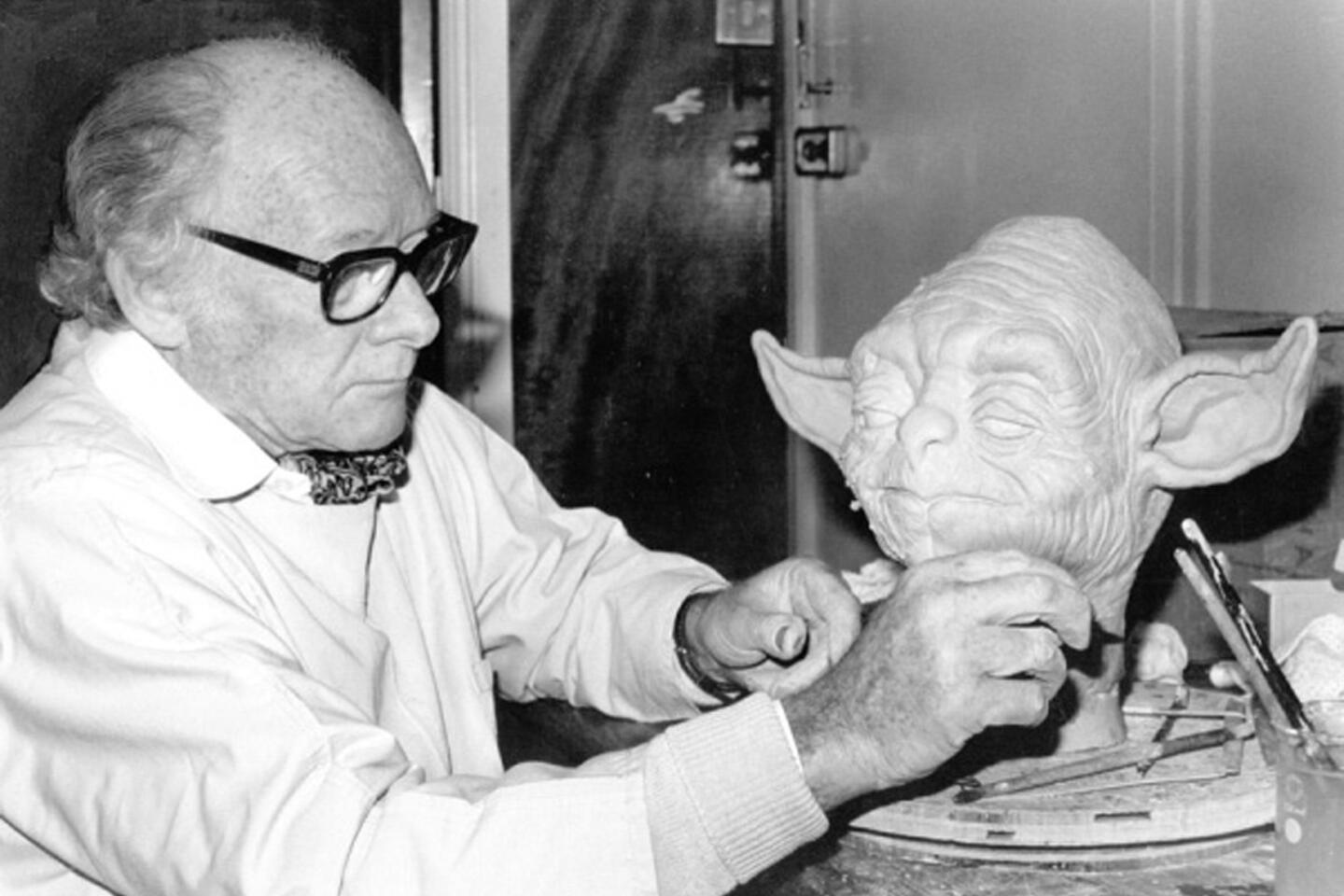

For decades, the Benedictine monk spent half the year working in a studio at an abbey in Belgium, painting abstract art in varying shades of white. For the other half, he took in the High Desert summers at St. Andrew’s Abbey in Valyermo, where he made “cookies,” his name for the folksy porcelain plaques he designed depicting angels, saints and biblical scenes.

“For six months of the year, I’m a serious artist,” he told The Times in 1986, “and for six months a year, I play with dolls.”

Van Doorslaer, whose earth-colored ceramics became a money-maker for the Antelope Valley abbey and a fixture for decades at its annual fall festival, died Friday of complications relating to colon cancer at a hospice near the religious order’s mother abbey in Bruges, Belgium, said Father Francis Benedict, abbot emeritus of St. Andrew’s. He was 87.

Van Doorslaer’s angels, which feature wide-open eyes and playful designs such as firefighter angels, angels with gardening tools, and angels with poodles, built him a loyal fan base across North America.

“It’s a very simple and kind of primitive art, but it does evoke spirituality,” said Benedict, a fellow monk who first met Van Doorslaer in 1965, when the California-based monks enlisted his help in finding an industry that could help sustain them financially.

After 10 months of traveling to Mexico and studying folk art, Van Doorslaer emerged with the trademark “cookie” design, so named because it reminded him of St. Nicholas cookies given to Belgian children. He later incorporated hobbies and sports teams into his designs to boost their popularity. “He created a recognizable trademark for us through those big-eyed saints and angels,” Benedict said.

Van Doorslaer’s designs sometimes showed flashes of his humor, such as a plaque of a troupe of angels playing cards or another of Jesus roller-skating with friends at Venice Beach, which was adapted in 1997 for a mural on the exterior of a Venice church. Today, the abbey produces 40,000 ceramic pieces a year for sale from 600 retailers and its online store. The abbey’s fall festival, where collectors often stood in long lines to get their angels autographed by Van Doorslaer, was discontinued in 2009.

Van Doorslaer seemed to relish his California summers.

Eschewing the monks’ traditional black robes for overalls and a sun hat, he could often be found under the shade of a peach tree, sketching his designs and speaking to children and other visitors about his art. “There was always a playful glint in his eye. He truly did enjoy interacting with people,” Benedict said.

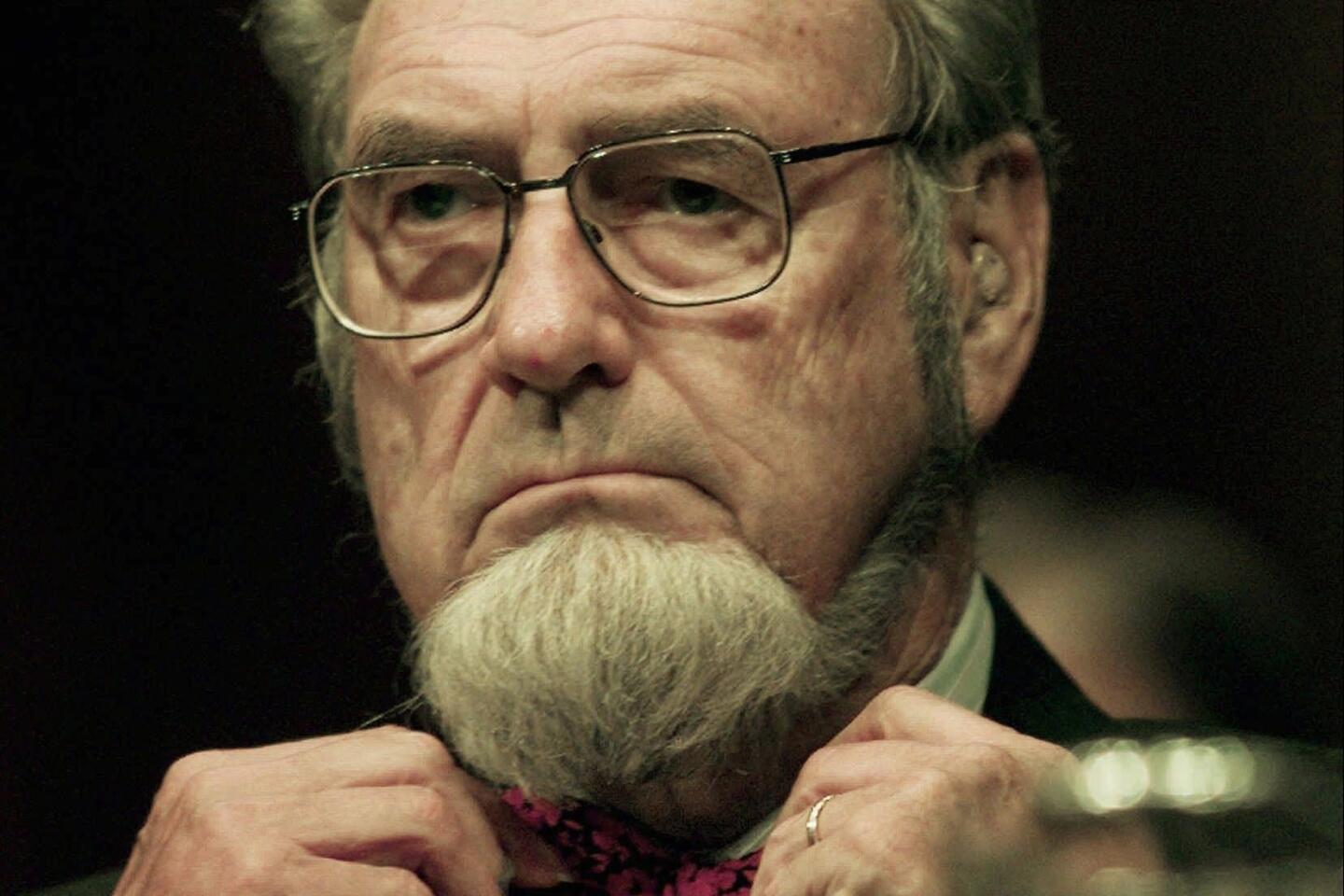

Every year before returning to Belgium, Van Doorslaer would call Los Angeles architect Frank Gehry, whose work he admired, and pay him a visit. Gehry said he was initially taken aback by the monk’s request to wander around the office and take pictures, but he obliged anyway. “There was a level of sincerity and honesty and respectfulness ... that was quite unusual,” Gehry told The Times this week. The next time Van Doorslaer came calling in 1989, he presented Gehry with a drawing of his wide-eyed angels, surrounding Gehry’s Vitra Design Museum in Germany.

Each year after that, Gehry received a new sketch — angels lifting cranes over the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, one year, horn-toting angels above L.A.’s Walt Disney Concert Hall another. Gehry collected the drawings and hung them in his office. One day Van Doorslaer brought one of his monochrome paintings. “That’s very different,” Gehry said. “Yes,” Van Doorslaer replied. “This is my real passion.” The painting now hangs in Gehry’s home.

Etienne van Doorslaer was born Oct. 1, 1925, in a small French village near Versailles, one of seven children. The next year his parents, who grew flowers, moved the family back to their native Belgium, where he was raised.

Van Doorslaer came of age in war-torn Europe; when he was 14, the Nazis marched on Belgium. Doorslaer was exempted from military service, but the chaos of war made him crave regimen and serenity, something he later said nudged him to the priesthood.

At 18, Van Doorslaer enrolled in an art school in Ghent. For six years, he drew, painted and studied architecture and sculpture.

In 1949, at age 24, he pursued a monk’s life, taking the religious name Maur, and was ordained in 1958. He was sent to Paris, where he continued his religious studies, visited galleries and painted. In 1961, he returned to the Belgian abbey and was assigned an art studio and charged with creating paintings to sell and to decorate the abbey, where a number of his monochromes still hang. But every summer, he returned to California to design new ceramics.

“These things showed up in grandmothers’ collectors cases and office buildings and dorms,” said Jerry Earl Johnston, a collector and columnist for Salt Lake City’s Deseret News who visited with Van Doorslaer several times during religious retreats. “He was able to take his art and use it to create a kind of spirituality that gets in the corner of people’s houses and lives that never would have gotten there otherwise.”

Information on survivors was unavailable.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.