Walter Cronkite dies at 92; longtime CBS anchorman

- Share via

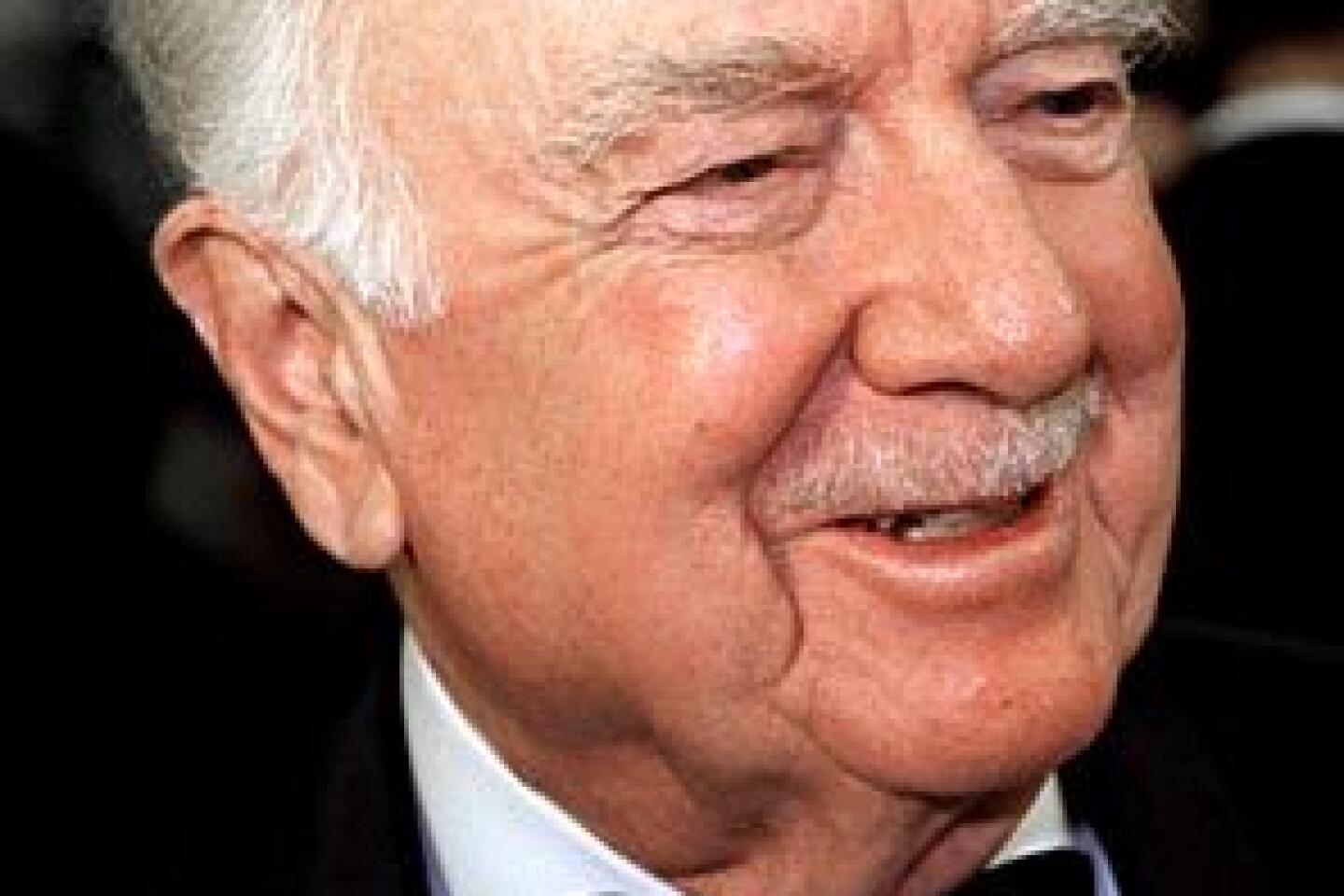

Walter Cronkite, the television newsman whose steady baritone informed, reassured and guided the nation during the tumultuous 1960s and ‘70s and who was still regarded as “the most trusted man in America” years after leaving his CBS anchor chair, has died. He was 92.

Cronkite died Friday at his home in New York after a long illness, according to CBS Vice President Linda Mason.

As anchor and managing editor of the “CBS Evening News” from 1962 to 1981, Cronkite exhibited a masterful, disciplined stewardship that helped television news come of age. He was arguably the most respected and recognizable media figure of his time.

“Walter was truly the father of television news,” Morley Safer, a correspondent for CBS’ “60 Minutes,” said in a statement. “The trust that viewers placed in him was based on the recognition of his fairness, honesty and strict objectivity.”

For two generations of Americans, Cronkite was a witness to history who also helped shaped perceptions of it. Although he rarely displayed emotion on camera, those moments are seared into the nation’s collective consciousness -- Cronkite tearing up while announcing the assassination of John F. Kennedy, decrying the “thugs” at the 1968 Democratic National Convention or exclaiming “Go, baby, go!” as Apollo 11 lifted off for the moon 40 years ago this week.

Raised in Missouri and Texas, Cronkite had a comforting Midwestern accent and an everyman likability. He came off as everyone’s “Uncle Walter,” an image he fostered by leaning back in his chair and fiddling with a pipe at the end of nightly broadcasts. When he signed off the news with “And that’s the way it is,” many Americans believed him.

President Johnson was watching CBS News in 1968 when Cronkite followed a report critical of the Vietnam War with rare commentary -- the anchor declared the war unwinnable and said the U.S. should pull out.

Johnson reportedly turned to an aide and said, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America.” Many observers speculated that this was a major reason Johnson decided not to run for a second term -- and offered to negotiate with the North Vietnamese.

“It was the first time in American history a war had been declared over by an anchorman,” David Halberstam wrote in the 1979 book “The Powers That Be.”

So entwined was Cronkite with modern U.S. history that a 1981 New Republic commentary seemed to echo the nation’s reaction when the magazine compared his retirement to George Washington’s face vanishing from the dollar bill.

Recruited by Murrow

He had been at CBS since 1950, when legendary newsman Edward R. Murrow recruited him for the network’s young television division. Cronkite had distinguished himself as a daring World War II correspondent for the United Press wire service who accompanied bombing missions and crash-landed in a glider.

The 1952 Republican National Convention launched Cronkite’s career and made clear television’s new dominance over radio. The broadcast also popularized an industry term -- “anchorman” -- employed to describe Cronkite’s central role in the convention coverage. Within hours, his performance sent an “electric excitement” through the Chicago hall, Gary Paul Gates wrote in the 1978 book “Air Time: The Inside Story of CBS News.”

Cronkite would go on to anchor more than a dozen political conventions and the elections that followed.

When he saw CBS floor correspondent Dan Rather get punched in the stomach at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, Cronkite’s voice shook with rage as he said, “I think we’ve got a bunch of thugs here, Dan.” It was a rare display of undisguised wrath, and Cronkite later said he regretted it because a news anchor should be “above the battle.”

At the same convention, Cronkite made what he considered his biggest mistake in television by failing to aggressively interview Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley, whose security force’s strong-arm tactics had outraged the press corps.

Clarifying the news

Cronkite’s “natural decency and cautiousness” prevented him from being a great interviewer, but he was an excellent editor who could synthesize and clarify the news for the masses, Halberstam wrote.

Because Cronkite usually took such pains to appear objective in his reporting, when he did show emotion it seemed to resonate with viewers.

The most famous TV footage of Cronkite shows him delivering the bulletin on the 1963 presidential assassination. After he is handed a wire report, Cronkite pauses to gaze at it, then says, “From Dallas, Texas, the flash -- apparently official -- President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time . . . some 38 minutes ago.”

Recalling the scene on a 2007 CBS special in honor of his 90th year, Cronkite choked back tears as he said softly, “Anchormen shouldn’t cry.”

Over four days in November 1963, Cronkite showcased his ability to work without a script as CBS suspended regular programming to cover the aftermath of the assassination. Praise of the coverage invariably cited Cronkite’s dignified performance during what is regarded as the nation’s first period of electronic mourning.

From that point on, the public largely viewed Cronkite as solid and reassuring as he guided viewers through some of the most tumultuous times in U.S. history, including the 1968 assassinations of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy.

As early as 1966, Time magazine had called the anchor “the single most convincing and authoritative figure in TV news.”

Years later, as the Watergate scandal unfolded, CBS was careful to credit Washington Post sources and carry White House denials. But the 14 minutes that Cronkite devoted to “the Watergate caper” on Oct. 27, 1972, made it “a real national story,” Halberstam wrote in “The Powers That Be.”

In the early 1970s, an opinion poll identified Cronkite as the most trusted public figure in America. Pollsters repeatedly used him as a benchmark to measure public trust in presidential candidates, and he led all contenders for years. His influence was said to rival presidents, and at least twice his name had been floated as a presidential running mate.

More than a decade after Cronkite left the evening news for retirement, a survey named him the “most trusted man in television news.”

‘Old Ironpants’

Colleagues nicknamed him “Old Ironpants” for his ability to sit in the anchor chair -- the day Apollo 11 landed on the moon in 1969, Cronkite reportedly was on the air for 18 straight hours.

He displayed boyish enthusiasm for the space program, which he called the biggest story of the 20th century and “one of our last great adventures.” He also saw it as an upbeat escape.

The 1960s were “the worst decade of our history perhaps, including the Civil War,” Cronkite said in a 2001 CNBC interview, yet at “Cape Kennedy, everybody was not looking down despairingly. They were looking up. . . . It made a difference in our country.”

Once the Russians had launched Sputnik in 1957, Cronkite was quick to realize space would be an important TV story and schooled himself in astrophysics. His mastery of the subject amused him because he had failed first-year physics at the University of Texas.

From Apollo 11 forward, Cronkite anchored space coverage with Walter Schirra, an original Mercury 7 astronaut with whom he got along famously on camera and off, which gave pause to colleagues who often complained that Cronkite hogged air time.

When the lunar module, the Eagle, touched down on the moon in 1969, Cronkite wiped his brow and reverentially confessed he had nothing to say. He was “overwhelmed, like most of the world,” he told Esquire magazine in 2006.

The anchor cut short a vacation to helm coverage of President Nixon’s 1974 resignation and anchored a 14-hour celebration of the nation’s 1976 bicentennial. Two months after Iran took more than 50 Americans hostage in 1979, Cronkite reflected America’s obsession with their plight by closing the newscast with the number of days they had been held.

The hostages’ release after 444 days coincided with President Reagan’s inauguration on Jan. 20, 1981, and Cronkite called it “one of the great dramatic days in our history.”

It was the last overarching public drama over which he would preside. He stepped down from the evening news six weeks later.

Faced with turning 65, Cronkite “thought it was time to ease up,” he said in a 2004 Orlando Sentinel story. “I had been fighting deadlines since the age of 16.”

Roots of his career

The son and grandson of dentists, he was born Walter Leland Cronkite Jr. on Nov. 4, 1916, in St. Joseph, Mo. His middle name honored Leland Stanford, founder of Stanford University.

An only child, Cronkite spent his first decade in Kansas City, Mo., then moved to Houston, where he became interested in journalism in high school after reading a story about the life of a reporter in American Boy magazine.

By his junior year at the University of Texas in Austin, he had dropped out for a reporting job with the Houston Press.

Returning to Kansas City in 1936, he was hired at radio station KCMO and met Mary Elizabeth “Betsy” Maxwell, who worked in advertising. Writing of their 1940 wedding nearly half a century later, he still called her “my gorgeous bride.”

In 1939, he joined the United Press and found that the deadline-pressure reporting appealed to his competitive nature, and he stayed for 11 years. His affinity for fact-focused, straightforward wire service-style reporting would help define the rest of his career.

By 1942, Cronkite was a World War II correspondent in London for the news agency. His poise and professionalism caught the eye of Murrow at CBS Radio, but Cronkite preferred to remain a war correspondent, with future CBS colleague Andy Rooney, in “the Writing 69th,” the group of journalists who trained to fly on missions with the Army Air Forces.

After the war, Cronkite covered the Nuremberg war-crime trials of Nazi officers and was given a plum assignment: the Moscow bureau. But he and his wife found the city dreary, and Cronkite returned to the U.S. after two years.

Back in Kansas City in 1948, he essentially cobbled together a job as Washington correspondent for a string of radio stations in the Midwest.

CBS landed Cronkite in 1950 by promising that he could cover the Korean War but first assigned him to fill in at a Washington, D.C., affiliate. He was so good at explaining the war without film, often just using chalk and a blackboard, that network executives quickly decided to keep him at home.

With the 1952 political conventions around the corner, CBS officials saw that Cronkite had two crucial abilities -- he could ad-lib and make the complex sound simple.

His first post-convention showcase was a popular news-entertainment hybrid, “You Are There,” that featured reenactments of historical events. The program’s closing line -- “and you were there” -- somberly intoned by Cronkite, would reverberate through popular culture. He also hosted “The 20th Century” (1957-70) and other news-based series.

In 1960, Cronkite anchored the first network broadcast of the Olympics from Squaw Valley, Calif., when CBS aired 13 hours of the Winter Games.

Cronkite was 45 in the spring of 1962 when he replaced Douglas Edwards as anchor of the “CBS Evening News.”

With Cronkite’s urging, the nightly broadcast expanded from 15 minutes to half an hour on Sept. 2, 1963, and featured President Kennedy in one of his last interviews.

Throughout the 1970s, CBS News was at its peak of influence and was consistently No. 1 in the ratings. With Rather sitting in the anchor seat from 1981 to 2005, the broadcast largely languished in third place. Katie Couric took over as full-time anchor in 2006.

Before signing off the evening news for the last time on March 6, 1981, Cronkite said a brief goodbye: “Old anchormen don’t go away; they keep coming back for more.”

That was not to be the case. CBS rarely let him back on the air but kept renewing his contract.

Some speculated that Cronkite had been forced out to make room for Rather, but Cronkite and others insisted that wasn’t true.

“I just wanted to live a little, that’s all,” Cronkite told the Washington Post in 1986.

His last regularly scheduled assignment with CBS News was a 90-second radio segment called “Walter Cronkite’s 20th Century,” which ran for five years and ended in 1992.

The year he retired, Cronkite was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Arizona State University had named its journalism school after him in 1984.

New venture

In the 1990s, Cronkite experienced something of a career renaissance after forming a production company with his son and another partner. He produced dozens of documentary programs for the Discovery Channel, PBS and other networks.

When Sen. John Glenn (D-Ohio) returned to space at 77 in 1998, so did Cronkite, at 82, to co-anchor CNN’s coverage. He continued hosting the Vienna Philharmonic’s New Year’s Eve concert until he was 91.

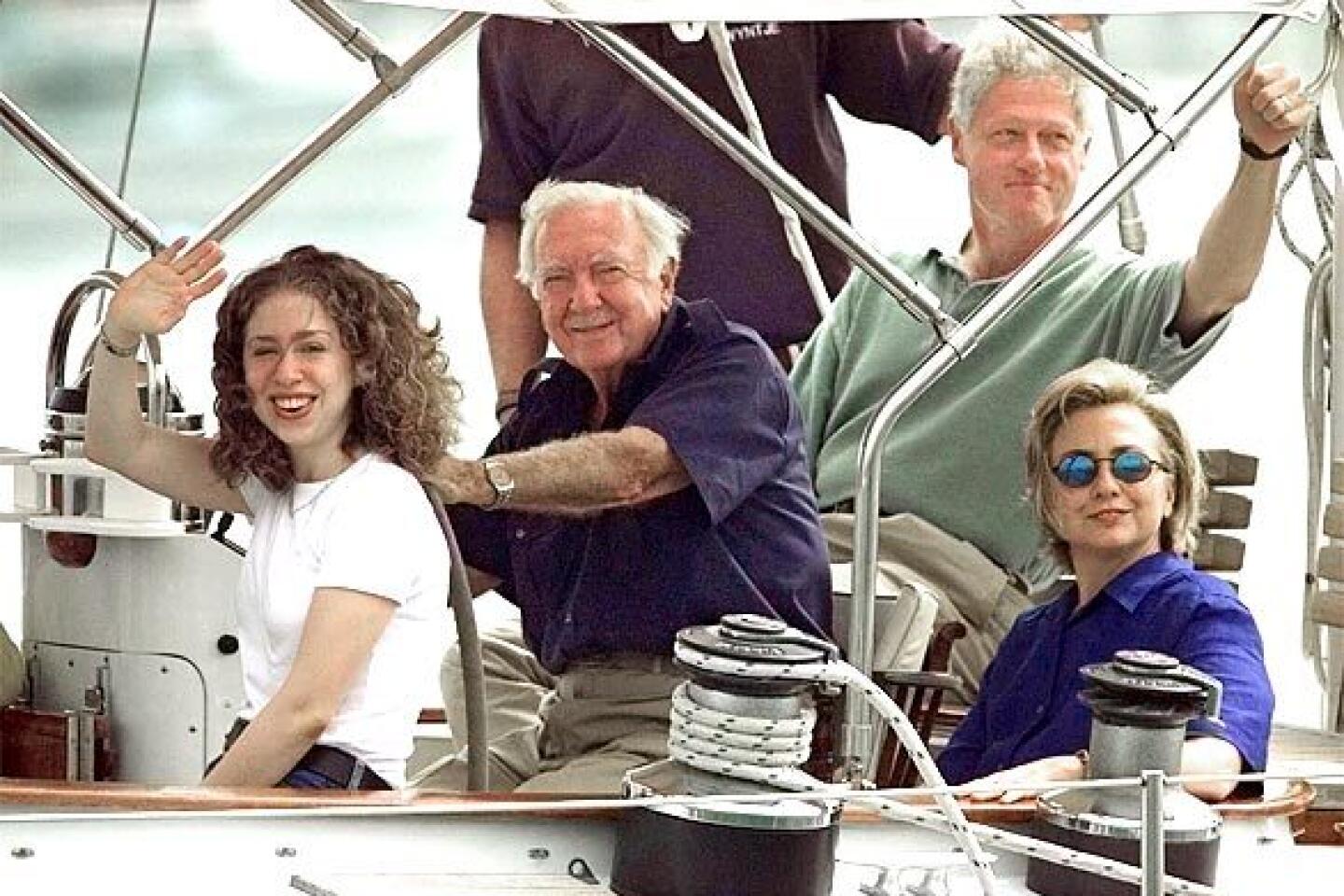

In retirement at his home in Martha’s Vineyard, Mass., Cronkite pursued his lifelong passion for sailing on his ketch named the Wyntje and wrote books, including his well-received 1996 autobiography, “A Reporter’s Life.”

At home, he was “gregarious,” relishing “spinning a one-line joke out into an elaborate shaggy dog story,” daughter Kathy Cronkite once recalled.

He expressed regret about being so aloof at work but was known for his hilarious parody of a burlesque queen’s striptease -- he ultimately removed no more than his jacket and tie -- at his annual Christmas party for CBS colleagues.

Cronkite often joked that he should have been a song-and-dance man and reveled in his wife’s sense of humor. They had been married for 65 years when she died in 2005.

Cronkite’s survivors include his son, Walter Cronkite III, who is known as Chip; his daughters, Kathy and Nancy; and four grandsons.

His mother, Helen, lived to be 101 and died in 1993.

Had he known he would age so well, Cronkite would not have given up the anchor job so easily or so early, he often said.

Nearly a decade after retiring, he was asked what news story he wished he could have been in position to cover.

“Every one,” he said.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.