Inside the minds of monks and moms

- Share via

IT MAY SEEM farfetched as you’re schlepping groceries or dragging your screaming 4-year-old to the time-out chair, but dedicated moms, you may have something important in common with meditating Buddhist monks.

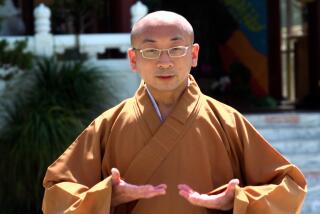

It’s the neurology of love and compassion -- a little-understood aspect of parenting. Brain-scanning studies led by University of Wisconsin neuroscientist Richard J. Davidson find that mothers gazing at pictures of their babies and Tibetan monks contemplating compassion both show marked activity in the left prefrontal cortex, an area apparently tied to happiness.

Davidson’s research on meditating monks (more extensive than his work on moms) suggests their brains also produce very strong gamma waves, which have been linked to concentration and memory. The findings were published in November in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The basic theory uniting nerve-wracked U.S. suburbs with Himalayan mountain monasteries is that love, compassion and equanimity can be thought of as “skills” that can be improved with practice and are capable of changing neural circuitry.

It’s surely a heartening notion. But if you’re skeptical, you’ve got company. Plans for the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s revered spiritual leader, to speak about the meditation research at next month’s meeting of the Society for Neuroscience in Washington, D.C., have sparked a fierce debate.

Some critics imply that Davidson, a longtime student of meditation, is too close to the Dalai Lama (who is a co-founder of the nonprofit Mind and Life Institute that helped fund Davidson’s studies). Others, charging research design flaws, say Davidson has failed to prove that meditation promotes compassion. The debate has even had political overtones because some of the opponents are of Chinese origin and may hope to squelch public attention to Chinese government repression in Tibet.

But the talk is still expected to take place, which is good news not just for science but for moms. (It’s good for dads too, although a recent U.S. Department of Labor report shows moms still spend twice as much time on family work.) Easily lost in our daily grind of haggling with soccer coaches and worrying about whether our kids should be taking Ritalin is one of the sweetest aspects of parenting: that when we put our minds to it, caring for children often boils down to basic training in positive emotions.

Let’s face it: Parents have extraordinary motivation and endless opportunities to hone “skills” such as kindness. In Davidson’s study on monks, the subjects concentrated on unconditional compassion, a pillar of the Dalai Lama’s teaching and described as the “unrestricted readiness and availability to help living beings.” What loving parent hasn’t noted some improvement in this capacity?

The hope that such changes may be concrete and lasting has to do with what’s known as brain plasticity. The 1990s’ “Decade of the Brain” revealed that human brains change and grow throughout our lifetime and that experience can rewire them. A violinist’s brain is demonstrably different from someone who doesn’t practice. A London taxicab driver, who must memorize that huge city’s maze, has on average a larger hippocampus -- the brain’s seat of memory -- than workers in other occupations.

Davidson suggests that sustained positive emotions can also have a concrete impact on the brain.

“Love as well as other positive emotions are not static but can be learned as skills,” he told a Canadian TV interviewer recently. “They’re skills that are not dissimilar from the skills that you might learn riding a bicycle.... If you train them, they will increase in strength and frequency.”

Davidson was talking about the normally joyful bond between a mother and infant, which he has called the “paradigmatic case of human love.”

Obviously, even the most devoted moms and monks differ in several glaring ways. Few moms of young children have much time to finish a thought, let alone meditate (though we might occasionally dream of escaping to Tibet rather than separating squalling siblings). Furthermore, no scientist to date has offered evidence that the repeated experience of a positive emotion, such as love, changes the brain permanently, although stress certainly can.

Frankly, there’s no question that Davidson’s work with both monks and moms is on the frontier of a scientific trend still in its infancy. But, like all infants in our compassion-challenged age, this research deserves a chance to grow.

KATHERINE ELLISON is the author of “The Mommy Brain: How Motherhood Makes Us Smarter” (Basic Books, 2005). Her website is www.themommybrain.com.