Memories can’t always be trusted, neuroscience experiment shows

- Share via

In courtrooms, on therapists’ couches and across the kitchen table, we count on the trustworthiness of our memories. But brain scientists are increasingly demonstrating that our recollections don’t exactly deserve the faith we put in them. They can be self-servingly Photoshopped, nudged off the mark by suggestion, and corrupted by being dragged out and rehashed.

Just how flimsy are the foundations of memory? So flimsy that in a neuroscience lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, researchers were able to fabricate fearful memories and implant them in the brains of mice using a few electrical probes, some photo-sensitive chemicals and a miniature flashlight.

For the mice, the false memory — of a painful shock delivered in a specific place in their maze — was more than a momentary fright: the creatures’ certainty that the memory was real could be gleaned from their behavior. As all bad memories are meant to do, this one taught the mice to avoid the spot in which they “recalled” getting a painful jolt.

“Memories can be unreliable,” the researchers noted in their study, published in Friday’s edition of the journal Science.

It’s one thing to suspect that memory isn’t always accurate; it’s quite another to recreate the process by which a false belief takes root in the brain.

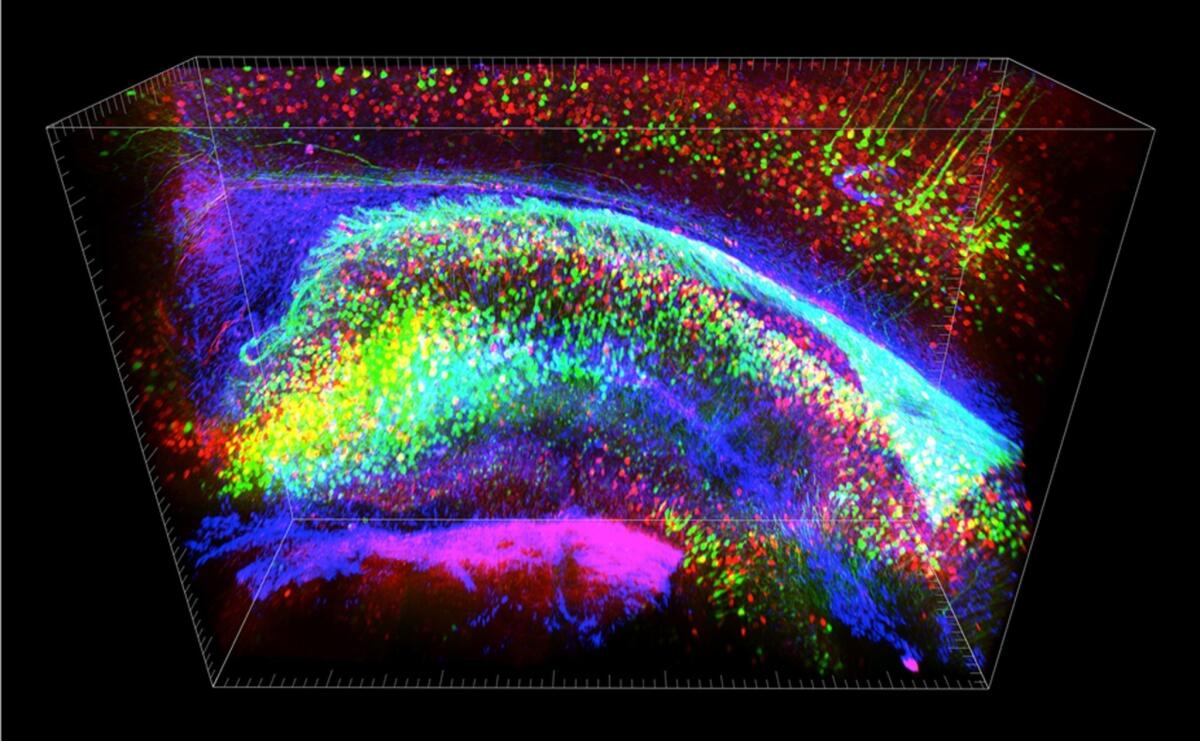

To do so, researchers first used a bit of genetic engineering to identify the specific cells in the hippocampus — a brain region key to the formation of memories — that were activated when mice found themselves in a specific, unfamiliar spot.

Half of the mice had those cells tagged with a light-sensitive chemical, so that at a later time the researchers could activate the cells with a tiny light-emitting probe. By doing so, they hoped they would conjure the memory of the specific spot.

The other half of the mice did not get the chemical tag.

Then, in a well-worn lab exercise, the researchers set about training the mice to be afraid of the selected spot. They shocked all of the mice’s feet by sending electrical current through the floor, which should have made them afraid of the place where they were standing. After repeated shocks, they will learn to avoid the place where they had experienced the shock: the memory of the association is a powerful guide to their future behavior.

But in this experiment, the researchers shocked the creatures while lighting up the memory cells associated with their recall of the spot they had previously explored.

The mice with the light-sensitive brain cells made the connection, “remembering” an association that never was: that the specific spot they had explored before was the place where they got a painful shock.

Given the opportunity to roam through a maze, these mice assiduously avoided the spot where they “remembered” being shocked. But the mice who lacked the light-sensitive chemical tag made no such false memory, and happily returned to the designated place.

The researchers, led by Susumu Tonegawa of MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and the RIKEN Brain Science Institute outside of Tokyo, suggested that some false memories may have origins in real experience but are then transformed beyond recognition.

When an original memory is brought to mind in the midst of new and different emotional circumstances, that memory may take on new and different emotional colors. A happy memory can turn dreadful if recalled in the moments before a car accident, or a frightening memory is defanged when revisited in the safety and support of a therapist’s office.

The latest research underscores that reliance on the memory of witnesses can be a poor guide to the truth in criminal cases, experts said. But it may also help pave the way to new treatments for such disabling conditions as post-traumatic stress disorder.

“With work like this, we’re going to have much more powerful techniques in the future to alter those memories, so they don’t become debilitating,” said Michael Fanselow, a professor of psychology and psychiatry at UCLA who was not involved in the MIT study. “As research progresses — and this is not going to happen tomorrow — we could not only put memories into the brain, but change memories of trauma that may be ruining a person’s life.”

Memory research, including that by Tonegawa’s group, also underscores why even painful and frightening memories can have remarkable staying power. In forming memories, we learn how to navigate challenges to our safety, Fanselow said. As a result, they are erased at our peril.

“We like to think we can recollect things that have happened in the past just to savor the memories,” he said. “But the real reason for memories is to guide our behavior in the future.”