Bill Nye, the (planetary) science guy, on NASA’s future

- Share via

What should the future of our space program be?

The National Research Council had unpleasant medicine for NASA in its just-released report on the vision and direction of the agency.

A panel of 12 independent experts concluded, among other things, that the program lacks clear direction from the White House and Congress about what its goals should be, and that NASA cannot do everything it aims to without more money. More cash is an unlikely prospect in the current economic climate, the panel also said. So the government and the agency have to decide what they want NASA to focus on.

The report made for “rather grim reading,” one space policy expert, Scott Pace of George Washington University, told The Times.

So what should NASA’s mission be? Do scientists and the public care about sending astronauts to an asteroid by 2025? Is it realistic to send astronauts to Mars in the 2030s? Are we focusing too much on Mars? Opinions on that vary, as our article noted.

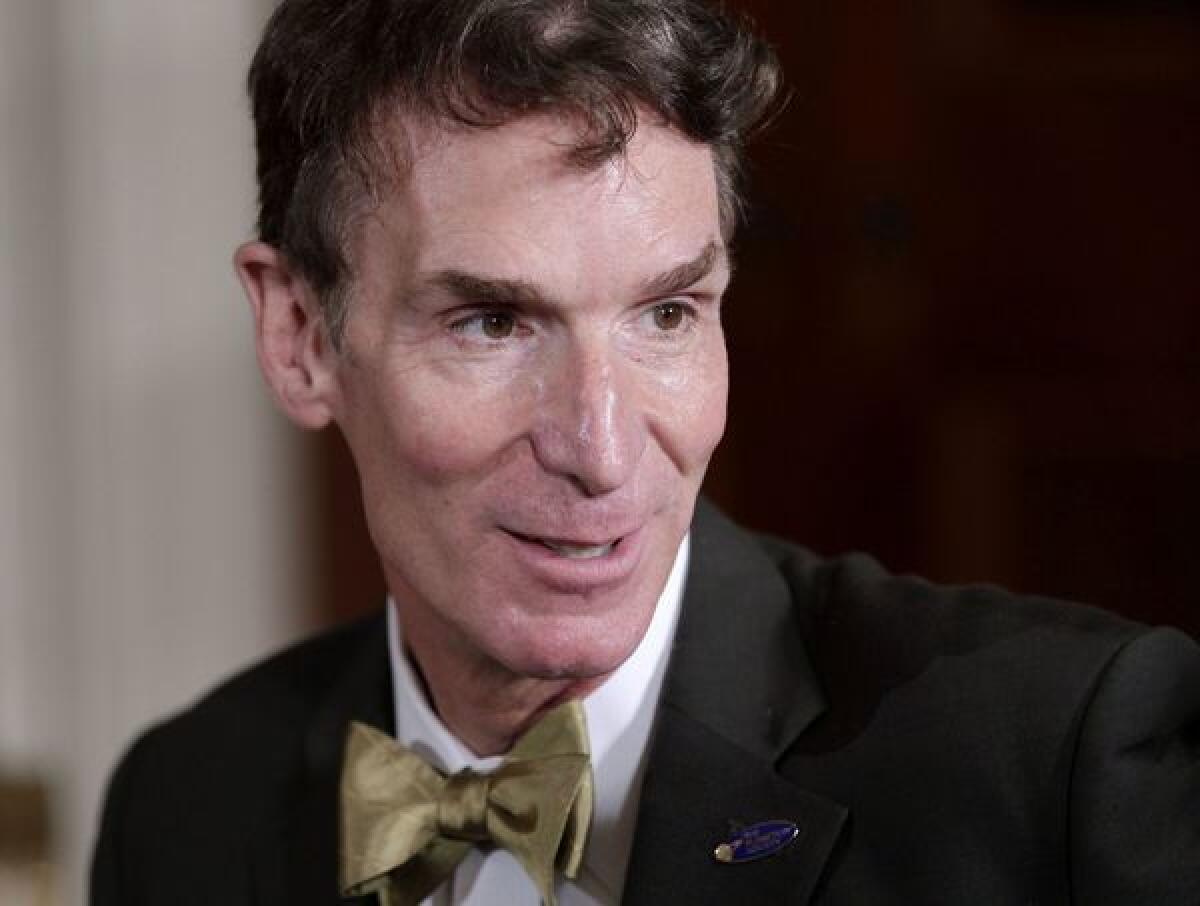

Here’s an interview with space exploration enthusiast Bill Nye (of “Science Guy” fame), the chief executive of The Planetary Society.

Of the NRC report: “Everyone would agree with it,” Nye said. “The thing is, what to do next? That gets into the difficulty of politics.” He said it’s no easy matter to reorganize NASA.

“If you had a corporation and you wanted to move 1,500 jobs from Jackson, Miss., Orlando, Fla., you’d just do it. You’d just say ‘I’m moving the jobs,’” he said. “But you can’t do that with NASA or government infrastructure because there’s congressmen and senators who will fight you about it to protect their people. … It’s a different management challenge.”

What NASA should be: “The report, to me, is getting to an old problem of what we want to do. I believe, as a country, we want to move NASA from [being] an engineering organization to a science organization, and this is going to take years, decades. Now, through investment, we have companies emerging that are exploring space on their own and will ultimately lower the cost of access to low-Earth orbit, which will free up NASA to go to these new and exciting places.”

More money -- or focused vision? Leaving aside the feasibility of snagging more money, Nye thinks the space program is worth every bit of what we spend on it. (He’s applied to be an astronaut in the past and so did Bruce Betts, Planetary Society director of projects. Obviously, he said, “We’re advocates.”)

“We -- people from my pedigree -- we always want to invest more in NASA. I strongly feel that every dollar spent on space exploration pays back twice, at least,” he said.

He’s not talking about Tang: Without the space program, “We wouldn’t have the Internet, we wouldn’t have smartphones,” he said. And, he added, “Space brings out the best in us, and at the same time its humbling. The more you learn about our place in space, the more you realize we’re probably not that unusual, we’re not that special.

“The cost of planetary science is so low compared to the cost, for example, of the International Space Station. We have a tendency to not embrace it to the extent that we at the Planetary Society think we should.”

So what should NASA do? Nye believes NASA’s focus should be on two deep questions that all of us wonder about: Where did we come from? And are we alone? “Those two questions drive all of us as humans. Everyone has asked those questions. Since you were a little kid you’ve asked those questions,” he said.

Missions to Mars: Nye believes that sending another rover to Mars in 2020 -- NASA announced its plan to do so earlier this week -- fits well with those goals. “We don’t want to stop what we’re doing on Mars because we’re closer than ever to answering these questions: Was there life on Mars and stranger still, is there life there now in some extraordinary place that we haven’t yet looked at? Mars was once very wet -- it had oceans and lakes. Did life start on Mars and get flung into space and we are all descendants of Martian microbes? It’s not crazy, and its worth finding out. It’s worth the cost of a cup of coffee per taxpayer every 10 years or 13 years to find out.”

Nye said it’s true that there are other spots in our solar system worth exploring for signs of life, but those others -- such as the wet ocean worlds of Europa (a moon of Jupiter) and Enceladus (a moon of Saturn) -- are extremely hard to send missions to. Mars, he said, remains our best bet.

And we need to bring back samples from Mars, he said: This was one of the principal goals outlined in the National Research Council’s Planetary Science Decadal Survey, released in 2011, which proffers advice on space exploration’s 10-year goals. “The amount of information you can get from a sample returned from Mars is believed to be extraordinarily fantastic and world-changing and worthy,” Nye said.

Here’s a link to the Planetary Society’s own project on how such a sample might be gotten, done in partnership with Honeybee Robotics.

But do we need to send people there? Nye says yes. “They explore, depending on how you estimate it, about 10,000 times faster than robots ... what [a robot] can do in a day a human can do in a minute. If we could get humans there we’d really be cranking.”

Visiting asteroids is worthy: “It’s not crazy to suggest the reason we haven’t heard from another civilization is because they did not pass the asteroid test. You can’t let your developed world get hit by an asteroid. If you do, it’s control-alt-delete for your civilization. We want to understand asteroids and their motion and we want to prepare -- I’m not kidding -- to deflect one. There are estimated to be at least 100,000 civilization-killing asteroids crossing the Earth’s orbit. Wouldn’t we want know where they all are? So it’s very reasonable to send people to an asteroid on our way to Mars.”

Doing it differently: These are no longer the 1960s, he said. It cost $151 billion in 2010 dollars to get men on the moon -- “When you spend that kind of money, you can put 12 people anywhere you want” -- and we don’t have that kind of money to throw around any more, he said. Instead, you want a steady long-term program with no major budgetary spikes that can prove tempting targets for the axing. “Budget spikes: That’s that’s when programs get canceled and abandoned. Things don’t stick around and people can’t plan.”

The moon effort, he said, “was a national thing, it was a Cold War effort: ‘We have to beat this other super power out there.’ Now it’s got to be more disciplined, frankly. A different style of management.”