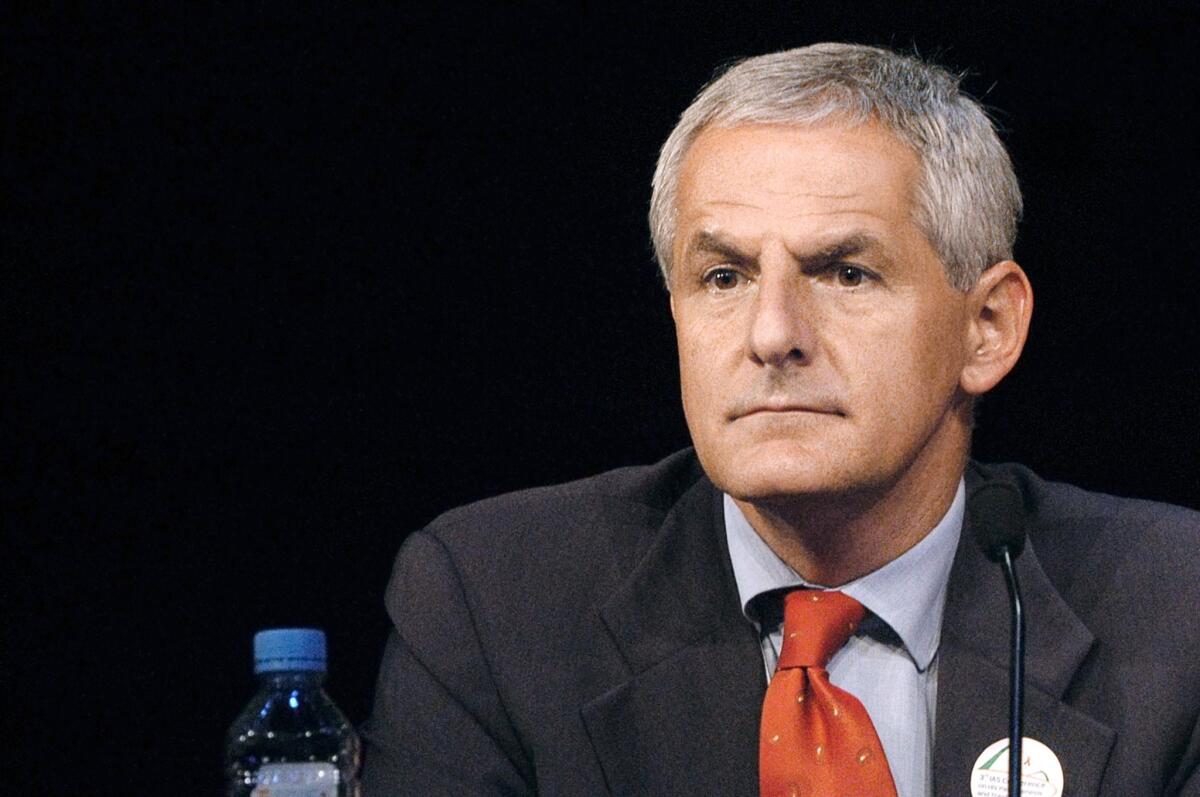

Pioneering AIDS researcher Lange was a star with a passion to help

- Share via

He wouldn’t be the only victim they knew, but he was probably the one they knew best.

Friends and colleagues of Joep Lange, who died Thursday on Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, remembered the prominent researcher as a straight-talking and well-liked figure in the field, who managed to combine a love for scientific rigor with a passion for helping people.

“He was a great scientist who cared deeply about doing something about HIV all over the world — a nice, nice man,” Thomas Coates, director of the UCLA Program in Global Health, told the Los Angeles Times.

Lange, 59, had been traveling from his home in the Netherlands to the 20th International AIDS conference in Melbourne, Australia, when the plane was shot down over eastern Ukraine.

The pioneering scientist had been working in AIDS research and advocacy since the earliest days of the epidemic, said Harvard School of Public Health professor Richard Marlink.

Many of Lange’s key contributions to the science of HIV occurred nearly 20 years ago, said Marlink, who first worked with Lange in 1992.

Lange, a professor of infectious diseases at the University of Amsterdam, was among the scientists who championed the use of a drug cocktail to battle HIV in infected patients, which remains the standard approach to keeping the disease at bay.

He also participated in clinical trials, Marlink said, that showed how treating the virus in pregnant and breastfeeding mothers dramatically reduced transmission of the disease to newborn infants.

In the years since, Marlink added, Lange had distinguished himself through his efforts to secure access to HIV care and treatment in underserved regions of the world, including Asia and Africa.

Fellow researcher Paul Volberding, who worked with Lange for nearly 30 years and considers him a close friend, recalls how Lange refused to listen to naysayers who said it would be too difficult to bring life-saving HIV medicines to rural villages.

“He said, ‘Look, you can be in a rural town in the African bush and buy a Coke,’” recalls Volberding, director of the AIDS Research Institute at UC San Francisco. “There was no way anyone could tell him we couldn’t do this. It was a matter of political will.”

Volberding said Lange early on embraced the role of large multinational companies and pharmaceutical firms in the uphill fight against AIDS, and partnered closely with companies like Heineken to increase access to care.

H. Clifford Lane, deputy director for clinical research and special projects at the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, worked with Lange on the HIV Netherlands Australia Thailand Research Collaboration (HIV-NAT) project, which set up clinical research centers in Thailand.

Lane said the effort epitomized Lange’s wide-ranging interests by managing to spawn new research and also deliver much-needed treatments to patients living in Thailand.

Speaking before he boarded a flight to join the meeting in Melbourne, Lane lauded Lange’s ability to “span all of those areas … from clinical research to molecular biology to public policy.”

Colleagues said they also appreciated Lang’s forthright honesty.

“He wasn’t afraid to be incisive and direct, and he was admired for that,” said Scott Hammer, a professor of medicine and AIDS researcher at Columbia University.

“He was a very kind, quiet, elegant person -- and measured,” Volberding said. “But he was not meek when it came to demanding access to care. His wit could be quite biting when someone deserved it.”

That was not to say, Volberding added, that Lange was not charismatic. He recalled one evening sitting with Lange at a hotel bar in Thailand, as Lange conversed easily with a Dutch princess.

“He had connections at high levels,” Volberding said, “and always used them to the advantage of people who needed care.”

Lange also had five adult daughters whom he adored and spoke of often, Volberding said, and was a passionate soccer fan and voracious reader.

For years now, the men have greeted each other at international conferences by asking what the other was reading, and swapping books.

“It’s very hard to reconcile his loss and so many others with a heartless trigger finger on the ground,” Volberding told The Times. “He was so much more important and good.”

Hammer suggested that Lange’s work was typical of the Netherlands’ contribution to AIDS research.

“It’s a small country that had a big impact on the early and middle years of the epidemic,” he said.

Dutch scientists are likely to bear the brunt of the disaster’s impact on AIDS research, Marlink said. Around 100 people aboard Flight 17 are thought to have been traveling to the AIDS meeting. In all, 189 of the 298 passengers and crew hailed from the Netherlands, the airline reported Friday.

Lange’s partner and colleague, Jacqueline van Tongeren, also died on the flight.

This is not the first time a high-profile aviation disaster has touched the far-flung but tight community of AIDS researchers, who criss-cross the globe regularly to attend conferences, and supervise and advocate for research.

In 1988, Irving S. Sigal, a molecular biologist who helped develop early drugs used to treat HIV, died when Pan Am Flight 103 exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland. A decade later, prominent researchers Jonathan Mann and Mary Lou Clements-Mann died on Swissair Flight 111, after it crashed into the ocean off Nova Scotia.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.