Must Reads: ‘Killed me little by little.’ Family detention left lasting scars for one mother and son

- Share via

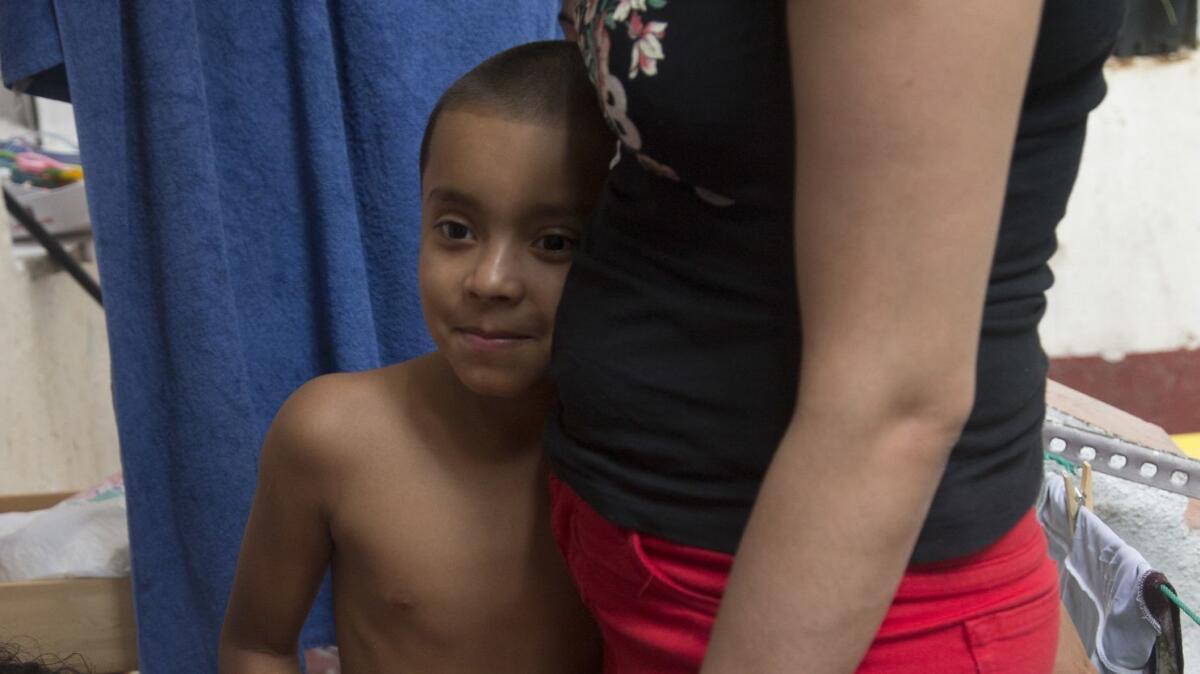

Reporting from Barcelona, Spain — For a long time, Lilian Oliva Bardales worried about how her young son, Cristhian, was adjusting to their new life in Barcelona.

He squeezed her every time he saw a police officer. He got scared when people he didn’t know talked to him. Teachers told her he played violently at school, making dolls fight and pretending to be an officer placing other children in handcuffs.

They asked if he had suffered trauma. As Oliva saw it, he had.

Before coming to Spain, Oliva and Cristhian had sought asylum in the United States and spent eight months in the Karnes County Residential Center near San Antonio, one of three family detention centers run by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Unlike hundreds of families taken into custody at the border in recent months under the Trump administration’s zero tolerance policy, Oliva and Cristhian were not separated.

Under fire for separating families, the administration has pushed to expand the use of family detention and loosen legal standards for facilities in order to keep migrant parents and children in custody. Administration officials and Republican leaders argue that facilities like Karnes are more humane than the alternative of family separation.

But to Oliva, 22, her son’s anxiety and aggressiveness were lingering effects of his time at Karnes.

“I wouldn’t want another child to suffer what my son suffered,” she said. “A detention center is not a place for a child or a mother.”

Family detention predates the Trump administration. It began in 2001 under the Bush administration and increased significantly under the Obama administration. Oliva and Cristhian, then 3 years old, were taken into custody in late 2014.

ICE officials recently issued a notice that they may seek up to 15,000 beds to detain families, though funding would be subject to approval by Congress. The three existing family detention centers — two in Texas and one in Pennsylvania — have space for about 3,500 parents and children.

Katie Shepherd, national advocacy counsel for the Immigration Justice Campaign, said the Trump administration is presenting a false choice by suggesting family detention is the only alternative to the policy of family separation. Some immigrants are released from detention with ankle monitors and telephone checkups. A study published Thursday by the American Immigration Council, an advocacy group, found that from 2001 to 2016, 96% of asylum seekers released from detention showed up at all of their court hearings.

While critics of family separation say splitting parents and children can traumatize children, Shepherd said children also can suffer when kept with their parents.

Shepherd represented families like Oliva and Cristhian who were detained in Texas under the Obama administration. She saw children regressing behaviorally, crying a lot, becoming listless, fighting more and lashing out.

She said children frequently got sick — the result of stress, eating unfamiliar food, and being held in what migrants call la hielera, or the icebox, because of the cool temperatures. She remembers some children passing out in their mothers’ arms and at least two being airlifted to San Antonio for medical care.

ICE officials challenge such characterizations. At a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing this month, Matthew Albence, the agency’s head of enforcement and removal operations, described family detention centers as being “more like a summer camp.”

“These individuals have access to 24/7 food and water,” he said. “They have educational opportunities. They have recreational opportunities, both structured as well as unstructured.”

For Oliva, the road to family detention began in spring 2014. That May she was caught attempting to cross the Texas border by herself. She had traveled solo because her abusive ex-boyfriend had threatened to kill her family if she fled with their son.

Four months after she was deported back to Honduras, she fled again, this time with Cristhian because the boyfriend was then in Mexico, working for a drug cartel.

This time, Oliva and her son turned themselves in to immigration authorities at the border in Hidalgo, Texas. But she said that because of her previous deportation, she was told she wasn’t eligible for bond.

Oliva and Cristhian’s days in detention were slow and monotonous. They shared a room with two other families and lined up in the mornings for guards to count them — the first of three daily headcounts. They’d watch TV or play bingo.

She said she was written up three times for bad behavior: once for playing soccer and leaving her son in the care of the other mothers, once for wearing sandals instead of the canvas shoes issued to her, and another time for allowing Cristhian to play with the other children unsupervised.

Cristhian turned 4 in detention. He made friends with the other kids, but noticed that they began leaving while he and his mother stayed behind. He also took note of other things — the tall walls around the courtyard, the fact that they hadn’t seen any cars in months.

Oliva noticed things too. Some guards called immigrants stupid and told her that should ask her own government for help.

“Why are we here?” Cristhian asked her one day. “This is a jail.”

“I told him, ‘We’ll be here a while and then we’ll get out,’ ” she recalled. “After five months, I couldn’t tell him that anymore.”

Department of Homeland Security spokeswoman Katie Waldman said the agency maintains the highest standards of care for people in its custody. “DHS take our responsibilities extremely seriously and perform them professionally and humanely,” she said.

In June 2015, Oliva reached a breaking point. She had received a letter from immigration authorities informing her that her petition for asylum had been denied and that she would be deported.

Oliva scrawled a two-page letter on ruled paper, signing it with her full name and her “alien number,” which ICE gives to all immigrants in custody.

“I write you this letter so you know how it feels to be in this damned place for eight months,” she wrote. “I do this because only God and I know what I suffered in my country. I come here so this country can help me but here you’ve killed me little by little with punishments and lies in prison when I haven’t committed any crime.”

When the 4 p.m. headcount came, Oliva locked herself in the bathroom. Guards found her bleeding from her wrist.

Oliva was bandaged and, she said, locked in a room alone for three days.

A few days later, she and Cristhian were back in Honduras.

Immigration officials said Oliva was treated for a “surface-level abrasion” to her wrist that was minor and not life-threatening, according to a McClatchy report in 2015.

That year Oliva and Cristhian fled to Spain, their flight paid for by Oliva’s pro-bono lawyer, Bryan Johnson. Spain doesn’t require a visa for Honduran tourists.

She initially planned to stay only until she could successfully appeal her asylum case in the U.S. An immigration judge ruled in 2016 that she had not received adequate legal counsel and could return to the U.S. But when Trump won the presidency, Johnson advised her to stay put. She applied for asylum in Spain.

Spain is increasingly becoming a destination for desperate Hondurans. Last year, Honduras was among the top countries of origin from which migrants sought protective status in Spain, according to figures released by the country’s interior ministry. Nearly 1,000 Hondurans sought protection that year, a more than twofold increase over the previous year.

Oliva was glad to learn that she wouldn’t be detained when she applied for asylum. Instead, officials offered her education courses through a center for mothers. Gradually, Cristhian began to put detention behind him, but it took time.

In June 2017, after Oliva and Cristhian received their first temporary residency cards and social security numbers, he started telling anyone who would listen that they had legal status. One day, as they were crossing the street near their apartment, he spotted a police officer.

“Hey, officer!” he called out. “You know, I have my Spanish papers now. And so does my mom.”

She doesn’t talk to him about their time in detention. “Now he’s better,” she said. “He’s starting to forget.”

On a recent humid afternoon, she watched as Cristhian and a cousin played on the terrace. She had purchased a blow-up pool but the water hose had broken, so the pool was empty. Still, the boys found a way to play, tossing stuffed animals into the pool.

“I’m a cowboy!” Cristhian giggled as he swung the broken hose over his head like a lariat.

“We’re always playing, all day,” the cousin said.

But for Oliva, it’s still hard to leave detention to the past. She recently dreamed about Karnes. It was unlike the nightmares she had the first few months after being deported, in which she’d wake up in a haste to line up for headcount.

In the new dream, Oliva had returned to Karnes as a Spanish citizen to observe the conditions and hear from detainees. She met mothers and fathers with their children from all over Latin America.

She asked the families when they expected to get out. They told her they were still waiting to find out.

Twitter: @andreamcastillo

Staff writer Castillo reported from Los Angeles and special correspondent Bernhard from Barcelona.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.