An iceberg the size of Delaware just broke off of Antarctica

A 1.12-trillion-ton iceberg twice the size of Lake Erie broke off Antarctica. (July 12, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

- Share via

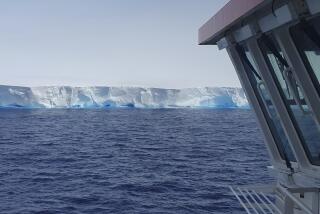

Sometime in the last few days, a block of ice the size of Delaware broke away from Antarctica and is now floating freely in the Weddell Sea.

The iceberg, which at around 1 trillion tons is one of the largest on record, poses no immediate threat to sea levels. But scientists say the break may have altered the profile of the continent’s western peninsula for decades to come and offers a preview of what global warming might do to marine ice shelves.

Scientists at Project Midas, a research team from Swansea University and Aberystwyth University in Britain, first confirmed the break Wednesday using data from NASA satellites.

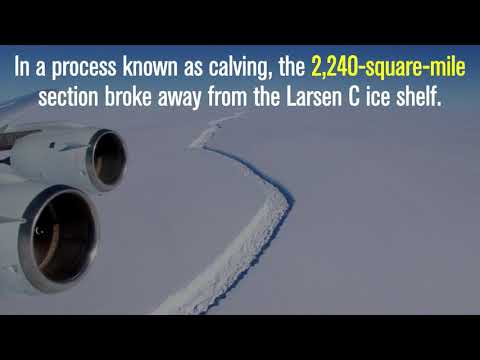

They said they had been monitoring a rift in an ice shelf called Larsen C for years before it started to grow rapidly in January, increasing in length to about 120 miles and leaving the iceberg hanging by a thread of ice less than 3 miles wide.

“We have been anticipating this event for months, and have been surprised how long it took for the rift to break through the final few kilometers of ice,” said Adrian Luckman of Swansea University, the project’s lead investigator.

What happens next to the iceberg is difficult to predict. “It may remain in one piece but is more likely to break into fragments,” Luckman said in a statement. “Some of the ice may remain in the area for decades, while parts of the iceberg may drift north into warmer waters.”

There is debate about whether man-made climate change played a role. For most of the second half of the 20th century, the Antarctic Peninsula was one of the fastest warming places on the planet, though that warming has slowed and may have reversed slightly in recent years.

Martin O’Leary, a glaciologist at Project Midas, said icebergs break away naturally in a process known as calving. “We’re not aware of any link to human-induced climate change” in this case, he said.

Even if that is so, scientists say the event will serve as a proxy to help them study how ice shelves fracture, providing a rare opportunity to gain a better understanding of how rising ocean and air temperatures could affect the region.

This particular calving reduced Larsen C by more than 12%, which some worry could have a destabilizing effect on the remainder of the shelf, among Antarctica’s largest.

These shelves — thick platforms of ice that float on the surface of the ocean at the edge of the Antarctic Peninsula -- are holding back glaciers that feed into them.

“When they break up, you just open the flood gates,” said Eric Rignot, a UC Irvine glaciologist and research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Named for the man who discovered it in 1893, the Norwegian explorer Carl Anton Larsen, the Larsen Ice Shelf is actually a series of many floating chunks of ice. Larsen C, the largest, was first photographed in the 1960s. Even then, the fateful crack was already visible, according to NASA.

Ice shelves form as ice sheets — large accumulations of snow on top of a land mass — flow downhill to the ocean. The shelves naturally shed weight in the form of icebergs — the process called calving — or through melting on the bottom.

“That’s just the way Antarctica works,” said Helen Fricker, a glaciologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego who studies ice shelves.

One way to know if a sheet is healthy is to see if it’s gaining as much ice as it is losing. Ice sheets grow as snow accumulates and freezes on the surface, and lose ice through melting and calving of their shelves. If a large enough iceberg calves off, an ice shelf could collapse.

That’s what happened to Larsen C’s neighbors, Larsen A and Larsen B, in 1995 and 2002 respectively.

More bergs will detach; it will become weaker and eventually fall apart in a domino effect.

— Eric Rignot, UC Irvine glaciologist and research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

A collapse of Larsen C is probably decades away, Rignot said. But the ice shelf has now retreated farther back than it has in the last 125 years.

“More bergs will detach; it will become weaker and eventually fall apart in a domino effect,” he said.

Larsen A and Larsen B held back relatively little glacial ice. But if all the ice behind Larsen C melted away, it would be equivalent to almost half an inch of sea level rise, Rignot said.

“As climate warming advances farther south, it will affect larger and larger ice shelves that currently hold back bigger and bigger glaciers, so their collapse will contribute more to sea level rise,” he said.

The George VI ice shelf, for example, holds back the equivalent of 11 inches of sea rise.

Twitter: @alexzavis

Twitter: @seangreene89

ALSO

Trump’s environmental rollbacks are hitting major roadblocks

Human chain of 80 saves family from drowning off Florida beach

California’s wildfire season has begun and you know the drill — or do you?

UPDATES:

6:50 p.m.: Updated with background on warming temperatures in the reason.

4:00 p.m.: Updated throughout with staff reporting.

6:01 a.m.: Updated with additional background

This story was originally posted at 5:10 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.