Mexico grapples with drug addiction

- Share via

HUITZILA, MEXICO — When the dope thugs beat him with a pistol, Rodrigo Sonck decided enough was enough.

He cleaned the gashes on his face and went to his father to plead for help: The cocaine life was killing him.

A month and a half later, Sonck was cloistered in a treatment clinic in the central state of Hidalgo, relating a tale of addiction that is increasingly familiar as growing numbers of Mexicans sample the drugs that once flowed through their country untouched.

For Sonck, a 28-year-old father of two, cocaine turned from an occasional party complement into an all-consuming, $700-a-week obsession. He sold his taxicab abruptly one night to get high. He had a chicken stand that met the same fate. The pistol-whipping came in August, after he raced off with his dealer’s merchandise.

Sonck had veered over the edge.

“It started as a game, and ended as a terrible disease,” he said.

The rest of Mexico is starting to feel much the same way. Once mainly a smuggling corridor for drugs heading to the United States, Mexico is grappling with the effects of a fast-rising addiction rate as relatively cheap versions of cocaine and methamphetamine find a market south of the border. Experts say the supply has increased as U.S. enforcement on the border has made it more difficult to move illegal drugs north.

A recent government survey of drug use shows Mexicans are trying drugs, and getting hooked, earlier in life and more frequently. The number of people who said they had tried drugs rose by more than a fourth, to 4.5 million, since the last survey in 2002. More than 460,000 Mexicans are addicted to drugs, a 51% jump from six years ago, according to preliminary results of the survey released last month.

Those tallies are undoubtedly too low. Officials said safety considerations prevented them from querying residents in two key drug-trafficking states, Sinaloa and Baja California, and hindered data collection in three others.

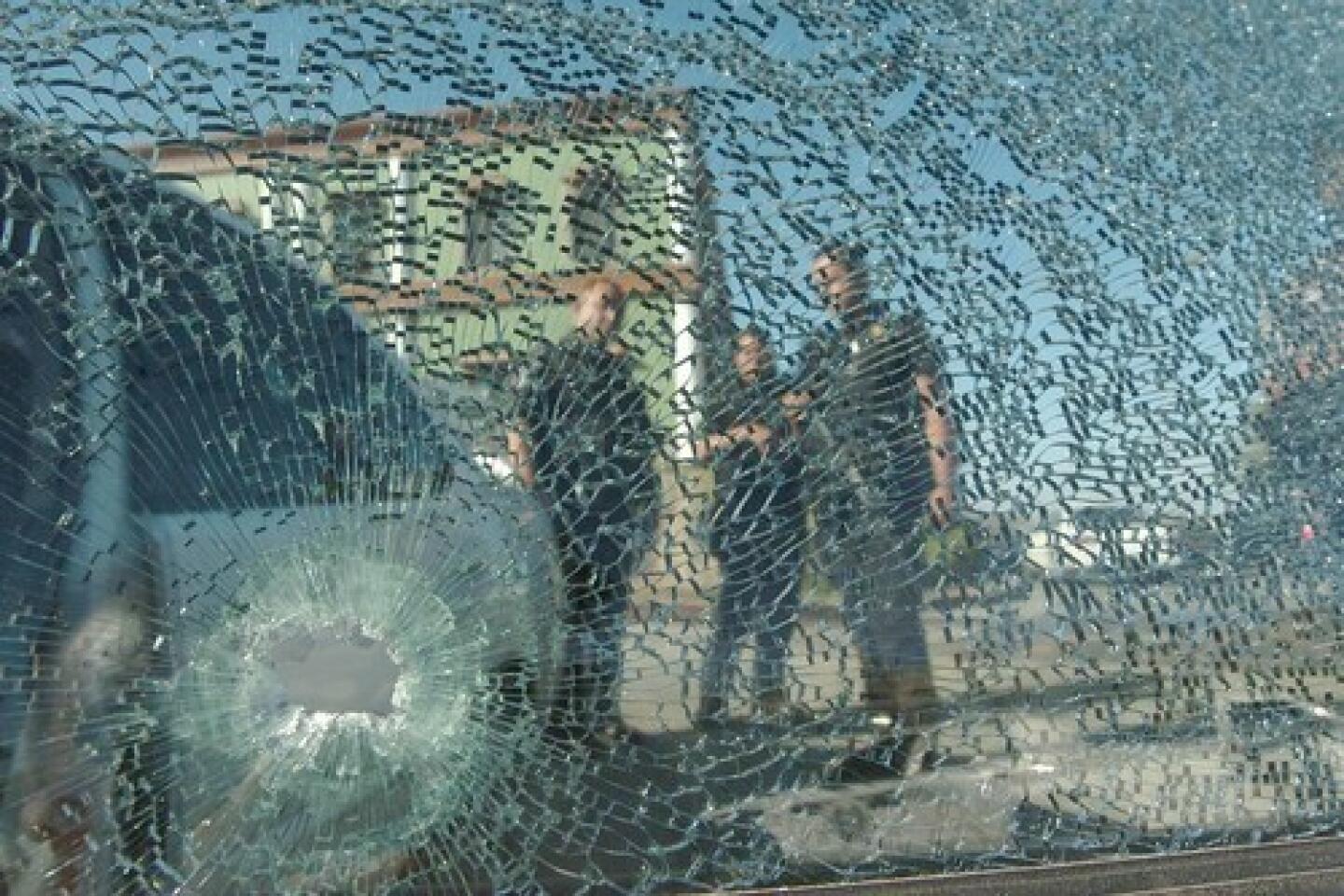

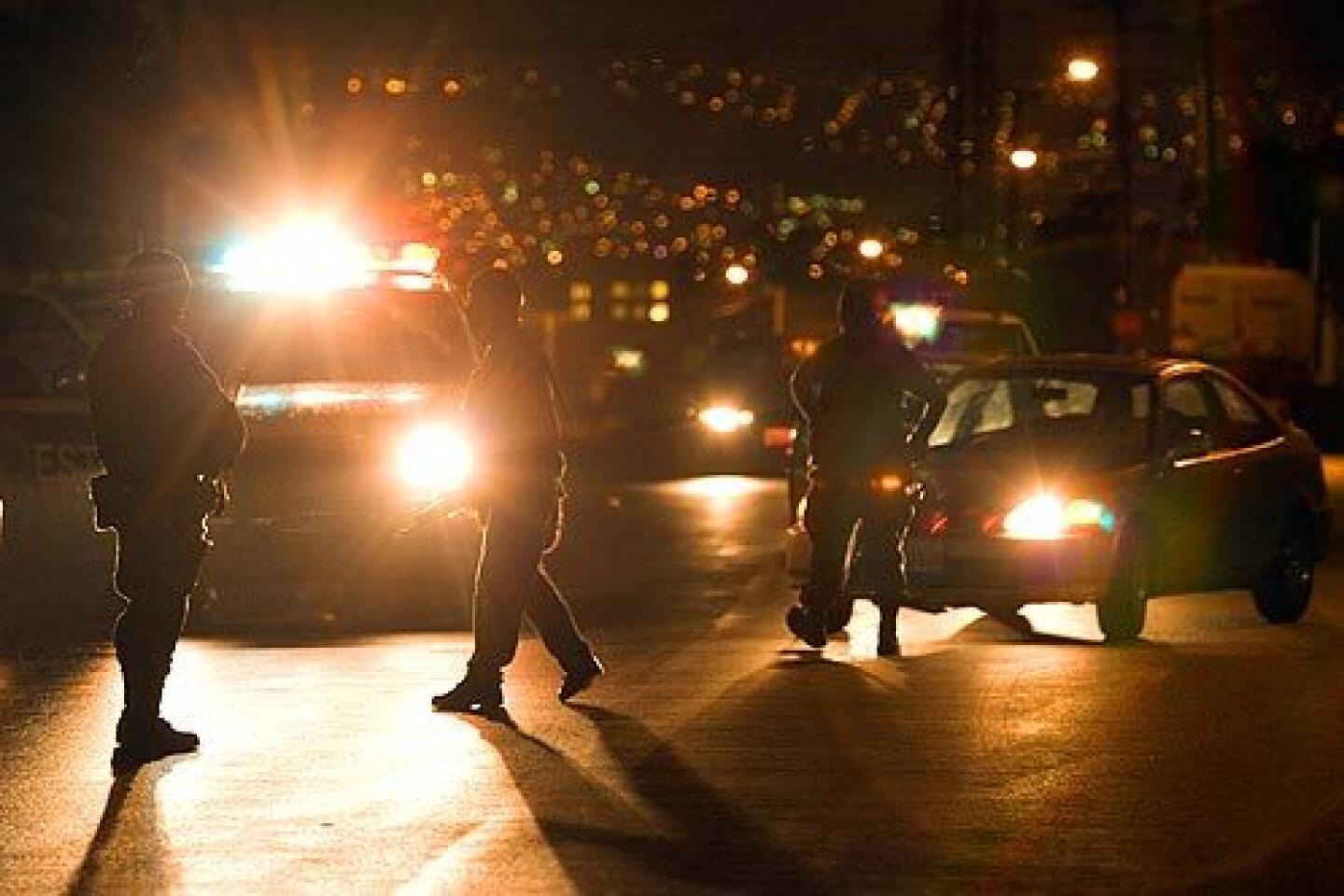

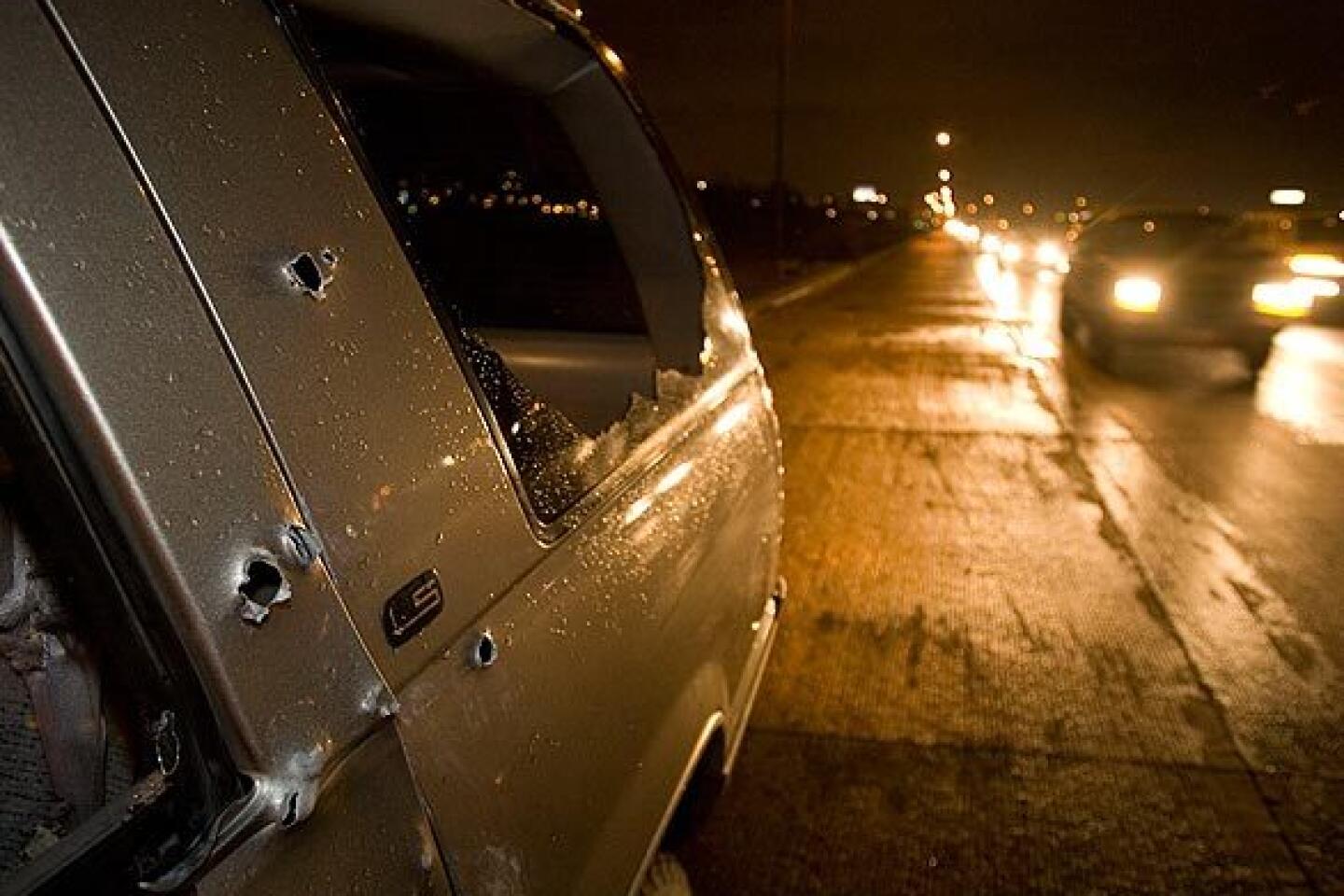

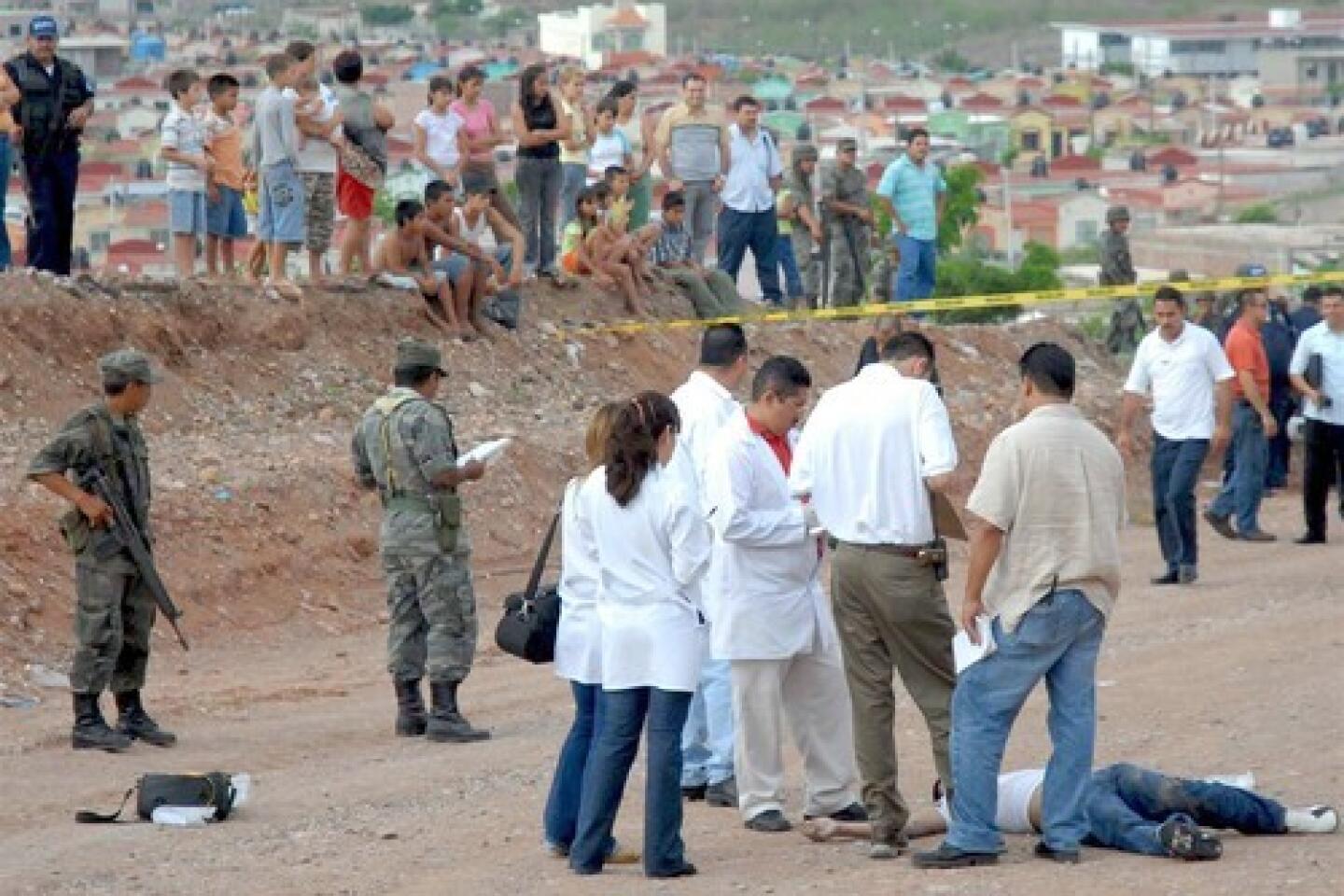

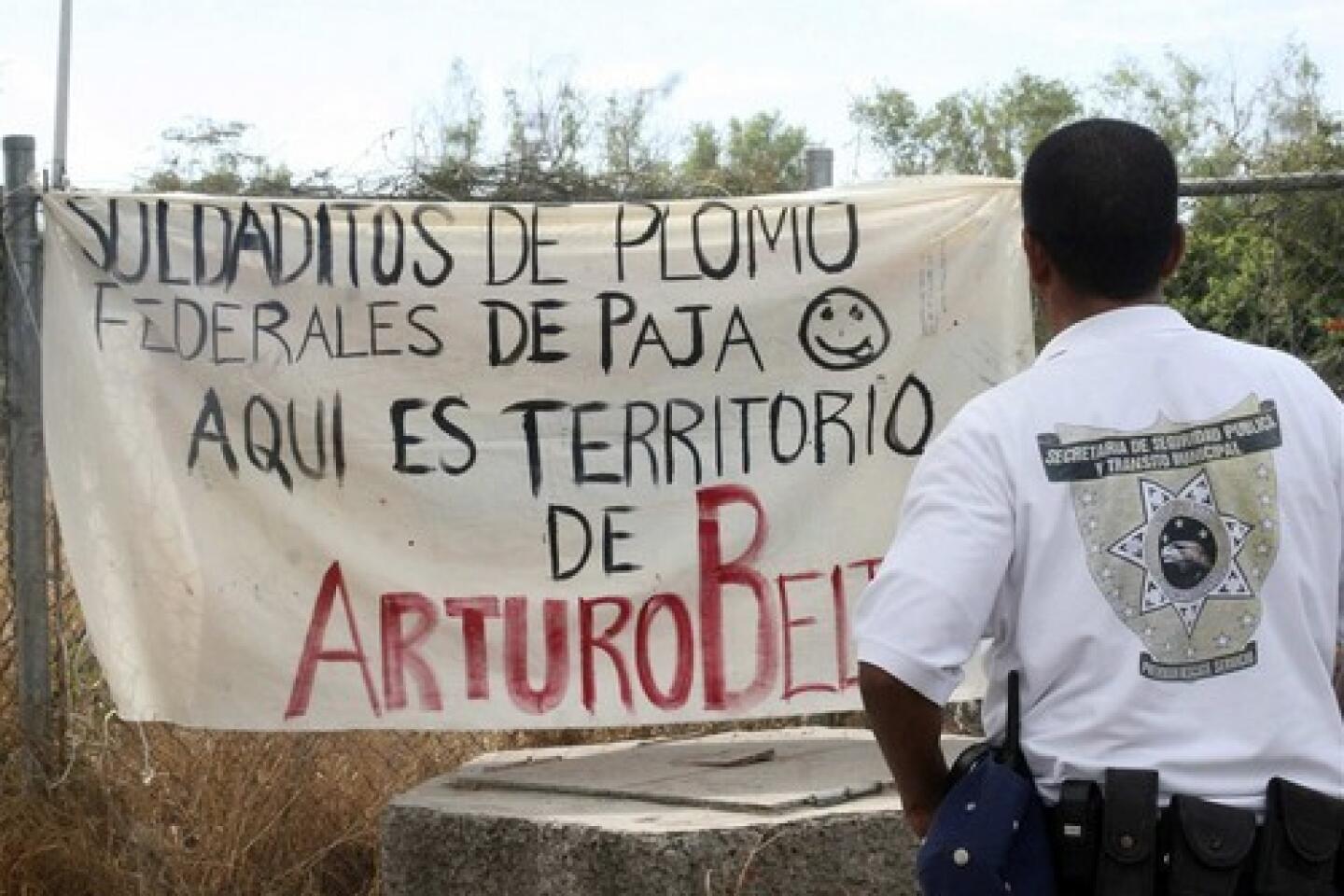

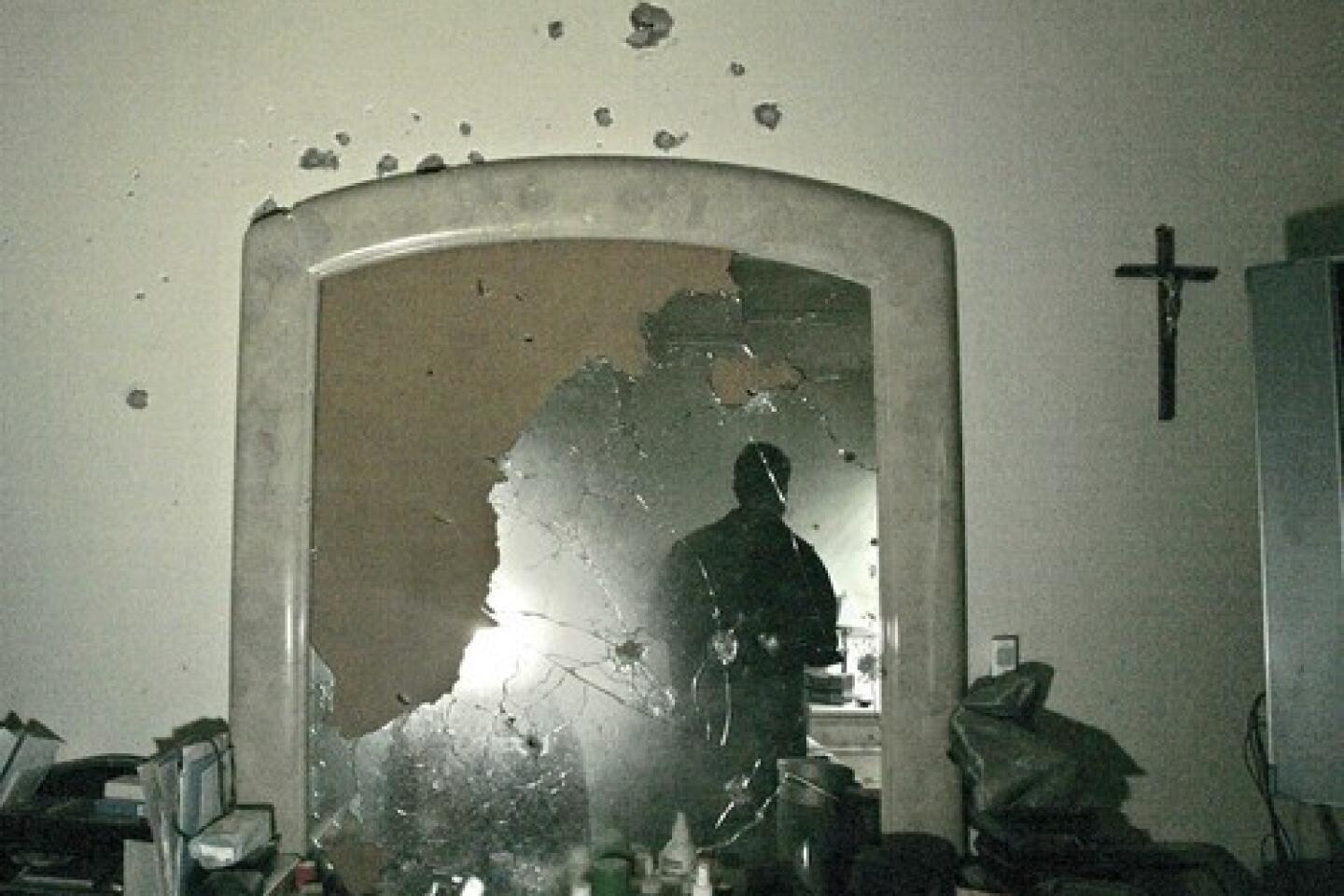

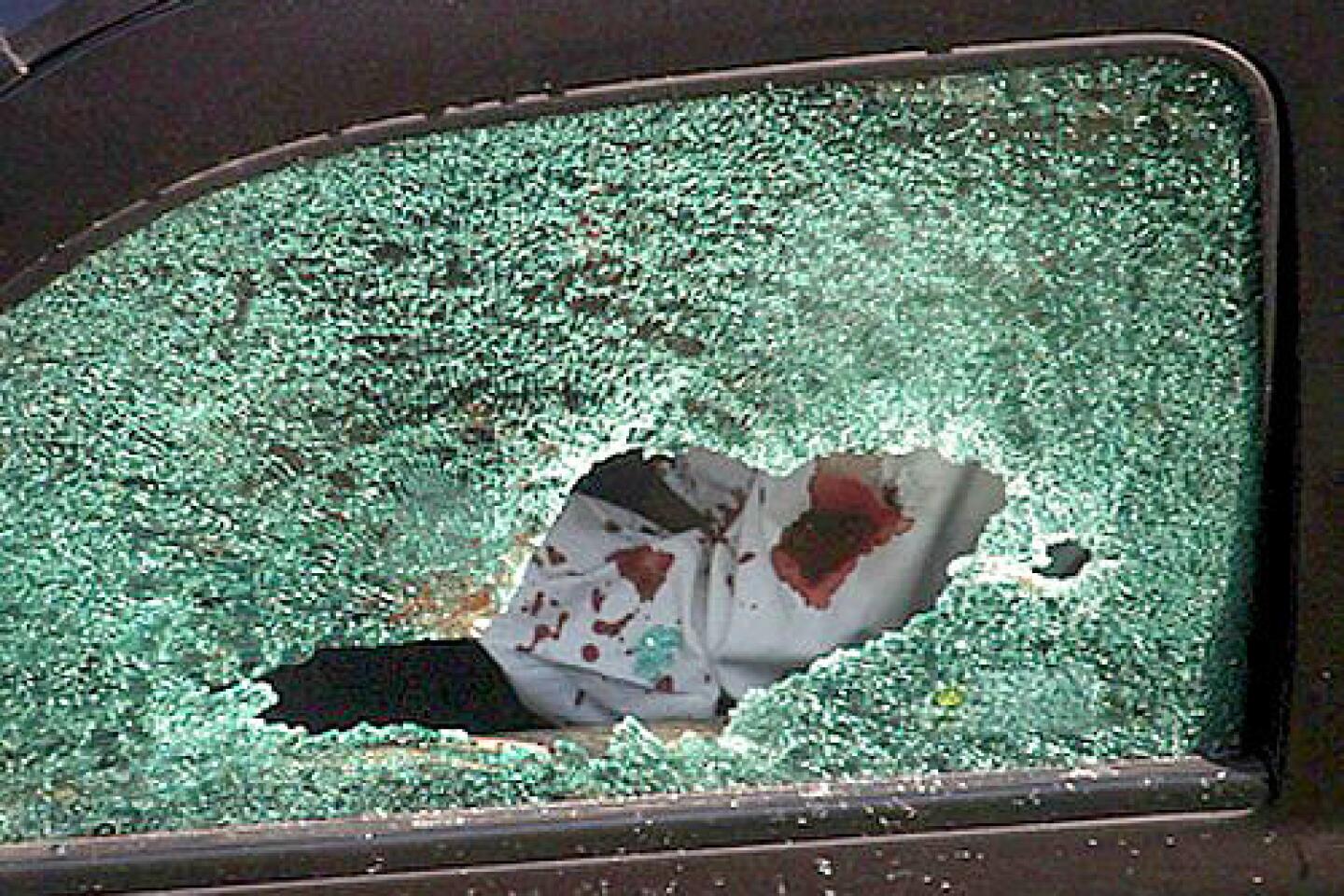

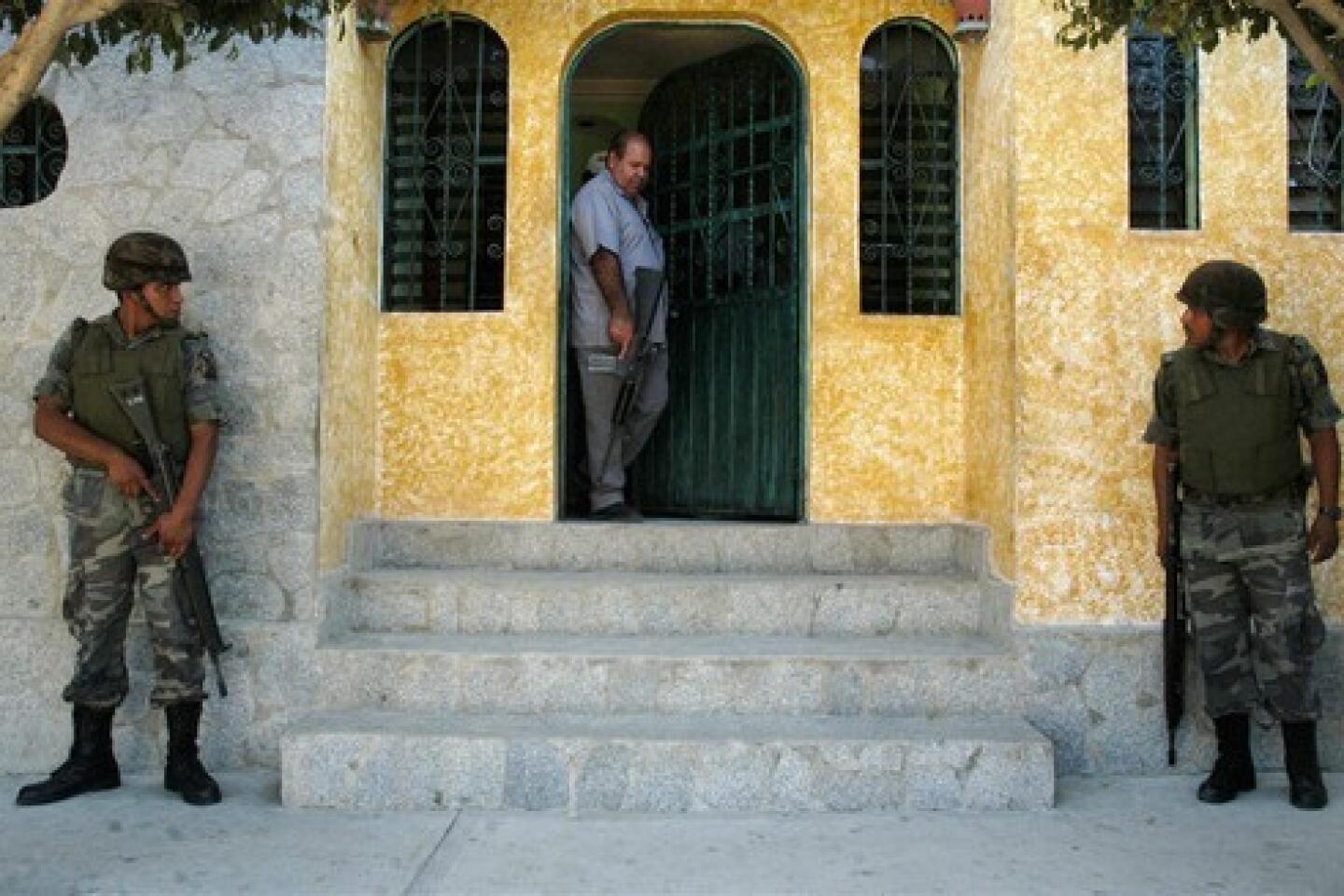

Growing consumption here presents a difficult new front in President Felipe Calderon’s war on drug traffickers, declared in December 2006. There are signs that the street trade, known as narcomenudeo, is adding to overall drug violence that has killed more than 3,000 people nationwide this year. Analysts say the well-armed gangs that have fought each other for control of key international drug-smuggling routes are battling over the market in Mexico as well.

The slaying of the mayor of a resort town outside Mexico City this month was in part linked to his resistance to local drug sales, authorities said. Media reports said 12 men whose headless bodies turned up in the Yucatan peninsula in August may have been killed as part of a narcomenudeo turf war.

Mexican leaders, who for many years have pointed an accusing finger toward the United States when talking about drug use, now acknowledge their nation’s own problem.

“It is clear to everyone that our nation has stopped being a transit country for drugs going to the United States and become an important market as well,” Atty. Gen. Eduardo Medina Mora said recently. “We are experiencing a phenomenon of greater drug supplies in the streets, at relatively accessible prices.”

Addiction is reaching all corners of a nation that is poorly equipped to cope. Some rural Mexican communities have watched drug use rise after migrant workers returned from the United States with a new appetite for cocaine and other addictive substances.

Experts say potent drugs, such as cocaine, have become affordable for Mexicans of modest means. Prices have fallen as domestic supplies have risen, in part because of U.S. efforts to tighten border security since the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

“They’ve gotten cheaper, basically, because there is more availability,” said Carmen Fernandez, who runs a nationwide network of 110 drug clinics, known as Juvenile Integration Centers, that are largely supported by government funds. “A lot of these drugs stayed in Mexico.”

Methamphetamine, a synthetic drug, is manufactured in Mexico and widely available. Officials in the northern border state of Sonora say consumption of crystal methamphetamine has quadrupled since 2002. They label drug use their biggest public-health threat.

In interviews, addicts confirm that illegal drugs are readily available and often less expensive than a six-pack of beer. Crack cocaine, known in Spanish as piedra, or rock, sells for as little as $3 a hit. Powder cocaine, folded into a stamp-sized paper bundle known as a grapa, is diluted with aspirin or other chemicals and sold for $5 or less.

In Mexico City’s poorest neighborhoods, such as the Iztapalapa and Tepito sections, dealers work from mom-and-pop stores, grimy housing projects and street corners.

“It’s like a plague that is invading us,” complained Ulises Ocampo, a neighborhood activist in the Tlalpan section of southern Mexico City.

Sonck said he had 25 spots to buy cocaine near his home in northern Mexico City. “It used to be something that was not very common,” he said. “Now everybody is involved.”

Calderon has proposed giving arrestees who are addicts or those caught with small amounts of drugs a choice of treatment rather than prison. The measure would also give local police a bigger role in trying to erase small-time drug dealing, at a time when federal forces are strained.

Administration officials insist the proposal won’t mean decriminalizing small amounts of cocaine and other drugs. The proposal wins qualified praise from critics who say the government has given short shrift to prevention and treatment in favor of a U.S.-style approach heavy on enforcement.

“There are not enough good treatment centers. There is not enough good prevention of relapses,” said Haydee Rosovsky, a drug scholar who formerly headed the government’s commission on addiction. “All the money is put in helicopters and soldiers and firearms.”

The Calderon administration has begun building 310 centers to improve outpatient treatment by helping specialists spot addictions sooner.

Janai Ramos needed help long before she got it.

Ramos, a 22-year-old addict in Mexico City, smoked crack through a glass pipe for the first time four years ago. “This is for me,” she recalled thinking.

The drugs were within easy reach: Ramos could buy from any of four nearby houses, side by side. She sank into long benders, emerging filthy and dehydrated after consuming nothing but crack smoke for four days at a time.

Ramos was soon smoking 15 hits a day, at $5 each. She made money selling fake-gold bracelets, but started stealing cellphones, hubcaps and truck mirrors to pay for more piedra.

Eventually she traded her body, selling sex up to five times a day to men she didn’t know.

“The truth is very ugly and degrading and humiliating as a woman,” Ramos said. Her round eyes were bright, but her voice seemed to come from a thousand miles away.

Ramos sought help several times, but relapsed. In late August, she checked into a clinic in Iztapalapa. She and three other women share a dorm-style room, spare but with a few paper flowers.

The men’s section has 24 people. All but two are coke addicts. They are up at 7 a.m. and fill the day with workshops, therapy sessions and household chores before lights go out at 10 p.m.

On the tough streets outside, an easy supply of drugs beckons, a fact of life in this new Mexico.

Cecilia Sánchez of The Times’ Mexico City Bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.