Doctors See Hope in Boy’s Battle With Rare Disease

- Share via

UCLA researchers who three years ago transplanted bone marrow into an 11-month-old boy with a rare, often fatal disease say that the transplant has been responsible for a significant improvement in the child’s neurological development.

“We now have evidence that we can change the course of this disease,” said Dr. Stephen A. Feig, chief of pediatric hematology-oncology. The doctor cautioned, however, that damage produced by the disease before the transplant may be irreversible.

The disease, called infantile metachromatic leukodystrophy, or MLD, causes degeneration of the brain and spinal cord because the individual lacks an enzyme necessary for the breakdown of a product that gradually destroys the central nervous system.

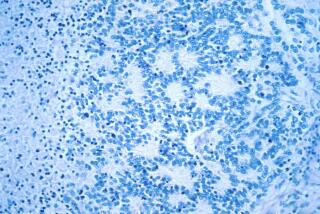

The UCLA team sought to provide the child with the enzyme by means of a bone marrow transplant containing white blood cells from his sister. The white cells served as a source of the missing enzyme.

Feig said the child’s parents had had two previous children with the same disease who had died at 3 1/2 years and 5 years of age. While both of those children had very serious neurological impairments, the third child has progressively improved since the transplant.

“We see no evidence that the progressive neurological development is slowing. But, of course, we have no long-term experience in follow-ups of patients like this,” the physician said.

As evidence that the transplant is the cause of the improvement, Feig said the medical team has been able to show that the white blood cells cultured from the boy’s spinal fluid are all female and, therefore, of donor origin. The finding is published in the Aug. 31 issue of the Lancet, a British medical journal.

Feig said that this is the first demonstration that cells from a bone marrow transplant are able to get into the central nervous system. Previously, he said, it was believed that the so-called blood-brain barrier would prevent white blood cells from entering spinal fluid.

The researcher said doctors also noted in the spinal fluid a decreased amount of the compound that destroys nerve cells when the enzyme is lacking, as well as an indication that the compound is being converted into a more harmless chemical.

According to Feig, the case opens the possibility that bone marrow transplantation may be effective in treating other disorders of the central nervous system that also involve missing enzymes in white blood cells.