Scholars Doubt Apocalyptic View of Jesus

- Share via

SOUTH BEND, Ind. — The view of Jesus as apocalyptic preacher, which has dominated biblical scholarship for nearly a century, appears to be facing its doom in mainstream studies.

The once unshakable consensus that the Gospels accurately reported Jesus predicting the cataclysmic end of the world is breaking down, according to most participants of an ongoing seminar of U.S. New Testament specialists.

During a three-day meeting that ended Tuesday at the University of Notre Dame here, the so-called Jesus Seminar polled participants on the question and found that only nine of 39 of its members believe that Jesus thought the end would come within his generation.

The majority of another group of Gospel specialists, a special seminar of the Society of Biblical Literature, also indicated in a mail survey earlier that evidence favors a non-apocalyptic Jesus.

The findings came unexpectedly for many professors here. They said that most popularly written biblical commentaries still show the influence of Albert Schweitzer’s 1906 book “The Quest for the Historical Jesus.” Schweitzer, who later earned world acclaim as a medical missionary in Africa, argued that Jesus’ primary message was apocalyptic and that all his teachings should be read in that light.

“I was frankly surprised at the shift,” said Robert Funk of Bonner, Mont., organizer of the Jesus Seminar, a group of more than 100 scholars engaged in a new quest for the historical Jesus.

Although the Jesus Seminar has drawn criticism for its unprecedented vote-taking on the validity of each saying of Jesus, its methods of historical-critical analysis, which tries to separate authentic sayings from words put into Jesus’ mouth by the Gospel writers, are standard for mainstream Protestant and Roman Catholic biblical scholarship.

Seminar members are typically professors of religion or Bible studies at major seminaries, religious colleges and state universities. Their involvement in the project is on an individual, academic basis, and not as representatives of church denominations.

Helmut Koester of the Harvard Divinity School and Bruce Chilton of Yale’s Divinity School--not members of the Jesus Seminar--told a Times reporter recently that they also do not see Jesus’ teaching as apocalyptic. Koester said he has never believed that Gospel sayings referring to the “coming Son of man” go back to Jesus. Chilton said he thinks scholars are nearly unanimous in believing that a series of apocalyptic predictions in the Gospel of Mark, Chapter 13, “didn’t come from Jesus.”

The newly perceived shift of opinion in these academic circles is not expected to affect fundamentalist and conservative evangelical scholars, who tend to denounce critical analysis as damaging to faith. All biblical words attributed to Jesus, regardless of their variety in content, must be considered true, conservative scholars say. These scholars have not shown any interest in joining the Jesus seminar proceedings.

Believers Shocked

“Many believers have been understandably shocked by the well-publicized statements of this Jesus Seminar group,” wrote the Rev. M. H. Reynolds of Los Osos, Calif., in a recent issue of the magazine published by his Fundamental Evangelistic Assn. Reynolds charged that “most of the theological students (in America) of our day sit under teachers holding similar or identical heretic views.”

The view of a non-apocalyptic Jesus is potentially good news for mainline churches, some scholars here said.

“This might give pastors the academic underpinning to return more confidently to the social gospel, which was undermined around the turn of the century by the apocalyptic interpretations,” seminar member Karen King of Occidental College said in an interview.

King was referring to preaching that focuses on Jesus as a model for social justice and service to others.

Bernard Brandon Scott of St. Meinrad (Ind.) Catholic Seminary added: “ ‘The new view’ definitely undercuts the picture of Jesus who will come as the Son of man to rescue the world from its failures.”

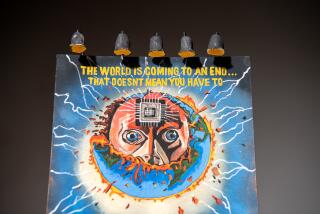

Scott suggested that Jesus’ image as an apocalyptic preacher and future world-saver has contributed to the feeling by many American Christians that the nuclear arms race is a part of the inevitable Armageddon but that believers will be saved for the coming kingdom of God on Earth.

But seminar members here deemed inauthentic, by close to a 2-1 margin, a saying attributed to Jesus in the Gospel of Mark (9:1): “Truly, I say to you, there are some standing here who will not taste death before they see that the kingdom of God has come with power.”

Similar sayings in Mark, Matthew and Luke have increasingly been under suspicion in the ranks of mainline scholars as products of apocalyptic expectations in 1st Century churches, decades after Jesus’ crucifixion.

Vernon Robbins of the Methodist-related Emory University in Atlanta said here that the swing away from an apocalyptic Jesus began mainly in the last 15 years among scholars who concentrated on the parables of Jesus, which are widely considered to be the most reliable examples of his teaching.

“The parables are trying to identify the activity of God where people are,” Robbins said. “They are not interested in talking about the angels and God in heaven and what a particular age will bring.”

Sayings in which Jesus appears to predict that widespread destruction will occur as a new age dawns actually make Jesus appear to be wrong--because it did not happen in his generation. But modern-day Christian apocalypticists who insist that neither the Bible nor Jesus, the Son of God, can be mistaken, have usually interpreted the sayings to mean that Jesus was not referring to his own period but to present time. Today’s wars and immorality are depicted as signs of the impending “last days.”

“How long can you play that game before you realize something is wrong with it?” one scholar asked.

Some Jesus Seminar participants are not ready to abandon the apocalyptic Jesus. Adela Yarbro Collins of Notre Dame said she does not consider every doom-sayer sentence attributed to Jesus to be historically reliable. “But I still think Jesus expected God to intervene in history, that he was influenced by Jewish apocalyptic views of his day,” Collins said. “It doesn’t bother me that things didn’t work out as he thought.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.