Book Review : On the Domestication of Mass Belief

- Share via

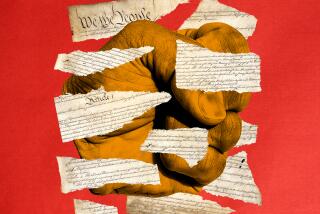

The Captive Public: How Mass Opinion Promotes State Power by Benjamin Ginsberg (Basic Books: $18.95)

According to Benjamin Ginsberg, the balance of political power in the United States today is shifting toward the right.

And this is happening not so much because of a realignment of party loyalties from Democratic to Republican but more because organized parties themselves are being displaced by new ways of mobilizing public opinion.

Not only that, but Prof. Ginsberg says we can no longer assume that governments in the West, which up to now have been more or less responsive to the will of the people, will endure. He thinks that a two-centuries-long window of opportunity for democracy may now be closing.

Briefly, Ginsberg says that authoritarian Western regimes have been forced by social disorder, external threats, civil rivalries or expansionist aspirations to extend suffrage to the bourgeoisie.

As a result of these concessions, governments began to attract popular support and were able to impose higher taxes, sustain standing armies and develop internal security forces. Moreover, the state discovered it could create a mass market for benefits and services, drawing to itself even more authority in the process.

At the same time, the people, although normally suspicious of the state, were nonetheless persuaded to surrender powers in the belief that government remained under their control.

Role of Public Opinion

Public opinion, of course, played a central role in this process. What Ginsberg calls the “domestication of mass belief” was engineered by governmental support for several key public institutions, one of which he identifies as the marketplace of ideas.

This market was promoted by state-supported education, mass literacy, a common language, speech freedoms, communications subsidies, judicial protection against censorship, libel suits, copyright encroachments, et cetera.

The result was that the wealthier, better-educated and more powerful producers of ideas (or those who hoped to increase their market share) began to promote their hegemony at the expense of the lower classes who, more and more, found themselves the objective of mass communications--on the receiving end--rather than the source of public opinion.

The suffrage is also a governmental device designed to domesticate public opinion. For Ginsberg, elections institutionalize opposition, they set the agenda, the scope, the frequency and the intensity of public opinion and channel public dissatisfaction away from more dangerous modes of expression.

If there had been an election in 1776, he says, the American colonies would no doubt have remained part of the British Empire.

In the Ginsberg scheme of things, public opinion polls are yet another important domesticating institution. Polls subsidize opinions, transforming them from voluntary and active expressions to effortless activities. They fragment political action from mass activity into uncoordinated responses.

They toss intense convictions overboard into a sea of apathy. They write the questions and, in most cases, write the answer choices, too.

Clues to Opinion Managing

The upshot of all this is that polls provide government with a way of finding out what the people are thinking before they can do anything about the situation and, when necessary, they supply the state with a better understanding of how to manage public opinion.

Public opinion polls also bear a heavy responsibility for the decline of political parties today and for the ascendancy of the right. A new battery of techniques for mobilizing mass consent (computers, phone banks, the broadcast media--especially TV--direct mail, public relations and, of course, polls) have shifted control over the levers of power from the left, with its superior organization and proximity to the people, to the right, with its vastly superior capital resources. And because these new mobilizing techniques are enormously expensive, political control is likely to remain with the right for a long time to come.

I hope you can tell from the above exposition that “The Captive Public” is tightly reasoned and thought-provoking; perhaps you can even tell that it is sometimes one-sided and polemical.

What I have spared you is Ginsberg’s tendency toward repetition--in fact, much of what appears here seems to be a reworking of his 1982 book, “The Consequences of Consent.” Even if you are not a pollster, you will perhaps be exasperated by this book, at times. But there is much here that is valuable.

What I find missing in this book is the lack of anything like a serious discussion of the role of the press in public opinion formation. There can be little doubt that governments make great efforts to manage mass attitudes.

But we tend to forget that the media increasingly control the means of production of ideas. Especially in the United States and in other nations that enjoy a large measure of press freedom, the fourth estate has assumed an interposing role with regard to governmental efforts at opinion management, and has become increasingly a representative of the public and an adversary of the state in their behalf.