Decision to Abort Can Be Made Sooner With Less Anguish : Need for Early Diagnosis Led to New Techniques

- Share via

The dilemmas fetal doctors now face daily rarely arose just 10 years ago.

The technique of amniocentesis dates back to the 19th Century, but doctors began using the procedure for prenatal diagnosis only in 1968, and even then it was restricted to a few isolated, experimental cases.

The purpose of drawing amniotic fluid is to obtain cells that have been generated by the fetus. The cells are extracted from the fluid, grown in a culture medium for about two weeks, then analyzed in a lab. Technicians can detect chromosomal disorders such as Down’s syndrome, biochemical disorders such as Tay-Sachs disease, blood hemoglobin abnormalities such as sickle-cell anemia, sex-linked disorders such as Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy, and neural tube defects such as spina bifida.

Risk of Fetal Damage

Amniocentesis involves some risk of infection, hemorrhage, fetal damage or abortion, miscarriage and embolism, but the latest studies place that risk at 0.2% or 0.3%, while calculating the accuracy of the diagnosis at more than 99.4%.

Until the late ‘60s, amniocentesis had been tried only during the third trimester of pregnancy, when a relatively high volume of amniotic fluid makes the procedure fairly safe. By then, however, it is too late for selective termination.

There was a need for earlier diagnosis, if the procedure was going to have a practical purpose. The first doctors to perform diagnoses on second trimester fetuses reported their findings in 1967. Amniocentesis now is done on fetuses as young as 15 or 16 weeks.

At first, only certain women were considered candidates for the procedure--those who had a family history or past pregnancies involving abnormalities, and those who were 35 years of age or older, where the likelihood of problems increases greatly.

More Young Women Tested

In recent years the use of amniocentesis among younger women has mushroomed. One study in New York state showed that the number of women under age 35 getting amniocentesis nearly tripled between 1979 and 1982.

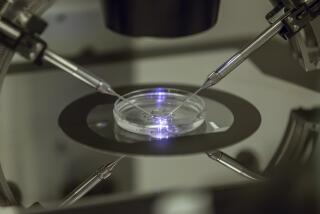

To do an amniocentesis, doctors such as Lawrence D. Platt, USC professor of obstetrics and gynecology, first study the fetus’s position in the womb on an ultrasound screen. They look for a pocket of amniotic fluid that provides a large enough target for their 3 1/2-inch, 20- or 22-gauge needle, safely distanced from the fetus.

Some doctors believe the risk begins at this stage, with the ultrasound. Some doctors discourage their patients from using the procedure, fearing ultrasound’s unknown long-term effects.

Cell changes have been observed in some animal studies, using much higher amplitudes and continuous long-term exposure. A National Institutes of Health study concluded that the vast majority of evidence does not indicate that ultrasound exposures at diagnostic levels are harmful. Yet the study also said, in essence, that more could be learned down the road. Ultrasound should not be used simply to determine sex or get a view of the fetus, the study concluded.

Some Feel Nothing

Once the doctor finds a safe pocket, he slowly guides the thin syringe through the abdomen, all the time looking on his ultrasound screen to see where it is entering the womb. The needle’s point, specially treated, shines fluorescently. Some women feel nothing, and some experience great discomfort. The doctor then withdraws enough amniotic fluid to fill three vials.

An experimental alternative to amniocentesis, now being tested under government regulation at several medical centers in the country, is a procedure called chorionic villi biopsy. A tissue sample is taken, by a tube passed through the cervix or the abdomen, from the outer membrane enveloping the fetus early in development. This sample is not an anatomical part of the fetus, but is considered identical to fetal tissue because it, too, arises from the fertilized egg.

CVB detects most of the same abnormalities amniocentesis does, except for neural tube defects. It is not as safe. Current studies suggest about a 5% risk of fetal demise, compared to a rate for amniocentesis of under 0.5%.

The great advantage CVB has over amniocentesis is timing. Amniocentesis cannot be done until the 16th week of pregnancy, and test results take two more weeks. By then, women can feel the fetus moving inside them, and they are visibly pregnant. CVB can be done in the ninth week, and test results are available almost immediately. Decisions to terminate pregnancies, when defects are found, can be made with less stress and anguish.

Amniocentesis results take two weeks because the fetal cells extracted from the fluid must be grown in a culture medium, dividing and redividing until there are enough to harvest and study.

This takes place at laboratories such as the one operated by the Genetics Institute in Alhambra. The system for analyzing the fluid is at once sophisticated and simple.

When technicians have enough fetal cells to study, they drop them on a plate. The cells break open, and the chromosomes are visible through a microscope. The technicians count them, hoping to find 23 matched pairs, 46 in all, the normal number. Then they photograph them.

Photographs Cut, Pasted

At the next station, a technician sits at a table with the photographs, cutting, pasting and arranging them into karyotypes--pictures of the 23 matched pairs of chromosomes, ordered in size from the largest (the No. 1 chromosome) to the smallest (the 22nd). The sex chromosomes, the X’s and Y’s, come at the end, as the 23rd.

Medical geneticists such as Robert Wassman, associate director of the Genetics Institute, spend much of their day studying these karyotypes. One in a hundred in Wassman’s lab is abnormal.

The ominous trisomies are easy to spot--an extra chromosome in a pair. A third 21st chromosome is Down’s syndrome, which results in mental retardation and some physical anomalies. A third 18th or 13th mean much more severe retardation.

Doctors rarely see the other trisomies, for they cause spontaneous abortions early in the pregnancy. Almost half of all miscarriages involve embryos with trisomy 16, or a missing sex chromosome, or triploidy, which is an extra of all 23 chromosomes.

‘Biggest Causes of Death’

“In all of human life, the biggest causes of death are these three,” Wassman said. “Not heart disease, not cancer. This is nature’s way of dealing with it. What we see and deal with are those that slip through nature’s net.”

Sex chromosome abnormalities pose some of the trickiest problems when deciding what to tell couples.

A female missing an X chromosome has Turner’s syndrome. A male with an extra X chromosome has Klinefelter’s syndrome. There may be extremely subtle structural abnormalities. Some studies suggest that there may be retardation, but there is debate over the researchers’ methodology. Women with Turner’s are short and sterile, men with Klinefelter’s tall and sterile.

Then there are those with an extra Y chromosome. Some years ago studies seemed to suggest that such men were unusually tall and overrepresented in jail populations. Some thought that a gene for criminality had been found. Later studies seemed to discount that notion, but it lingers.

Hard to Figure Out

Wassman also sees things that are simply hard to figure out.

He looks at chromosomes with a tiny spot on the top, or a minute gap in the middle. One chromosome may be curved oddly at one end, or flip-flopped on itself, an inversion.

“When you calculate how much DNA there is in the human gene, how long each protein is that the DNA codes for, you probably can put many thousands of genes on each one of those little bands on a chromosome,” Wassman said. “So if even a small part of it is missing or broken, a tiny spot, you may have a defect.”

What Wassman makes of an abnormality often depends on whether it is a familiar variation, well-described in scientific literature. He also wants to know whether one of the parents has the same variation and is healthy. He often turns to experts such as Larry Platt to do an ultrasound.

After all this, Wassman sometimes simply cannot reach an unequivocal judgment.

“It is hard to counsel couples on a 5% possibility of retardation,” he said. “I see some abort and we find afterward the fetus was normal. There are also some who don’t abort and there are malformations. I hold my breath waiting to see.”