Greatness Obscured

- Share via

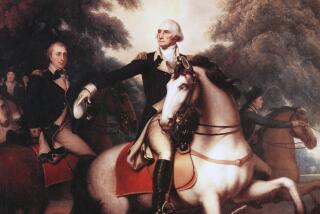

Stop for a moment on this generic Presidents’ Day and consider the man whom America should be honoring in singular fashion, George Washington. Schoolchildren know Washington because supposedly he chopped down a cherry tree and then confessed, threw a silver dollar across a river (the Rappahannock), suffered through Valley Forge, had a stern visage and wooden teeth, and was our first President.

Washington is our greatest national hero, yet the person is strangely shrouded in mystery and trivial legends. Speak of the 1787 Constitutional Convention during this bicentennial year, and James Madison comes to mind. But Washington’s presence as president of the convention was the force that held the group together when it threatened more than once to dissolve in dispute.

There might have been no convention at all had not Washington early on perceived the weakness of the Articles of Confederation and pressed for a strong national government with a vigorous executive. Many delegates were willing to grant the presidency unparalleled powers only because they knew that the office would be filled by Washington. He was so revered by his contemporaries that he was elected the first President unanimously.

Washington earlier wrote: “We are a young nation, and have a character to establish. It behooves us, therefore, to set out right, for first impressions will be lasting--indeed are all in all.” Once in office, he infused it with energy and set precedents that define our government and our national character to this day.

What was it that made this austere man unique? Historian Edmund S. Morgan wrote that Washington was not a man of many talents. He contributed little to the political thought of the day. He seemed aloof because of his native dignity and inborn reserve. But his remoteness should not be confused with arrogance, Morgan said.

Washington’s genius lay in his understanding and exercise of power--the gift of command. This gift worked in many ways. At the conclusion of the Revolution, many wanted Washington to seize power as a military dictator. Instead, he resigned his commission with great ceremony and symbolism, thus establishing the American tradition of civil control over the military.

Samuel Eliot Morison and Henry Steele Commager wrote of Washington: “He had the power of inspiring trust, but not the gift of popularity; fortitude rather than flexibility; the power to think things through, not quick perception; dignity, but none of that brisk assertiveness which has often given inferior men political influence.”

But beneath the cool exterior “there glowed a fire that under provocation would burst forth in immoderate laughter, astounding oaths or Olympian anger,” they said. Despite his reserve, he was known for many kindly acts.

Washington was eulogized in 1799 as “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” Two centuries later, the remarkable record and contribution of this complex and little-understood man yields to none. The real Washington Monument is the American Republic itself.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.