Joint Oil Venture Sought to Recoup $30 Million : A Teetering Shah Led to Bogus Billings

- Share via

DUESSELDORF, W. Germany — For Wilfried Tillmann, an ambitious, 40-year-old middle-manager at Europe’s largest steelmaker, the assignment handed to him in the autumn of 1978 seemed beneath his station: order a simple rubber stamp. But the $2.50 purchase would be one of the most significant and frightening experiences of his career.

Tillmann’s employer, the respected German industrial giant Thyssen Rheinstahl Technik GMBH, had been building a $1.2-billion oil refinery for the Shah of Iran in partnership with an American giant, the Irvine-based Fluor Corp. And, by late 1978, with the shah’s regime beginning to teeter, Thyssen-Fluor executives feared that the revolution would erupt before they got paid.

That is why Tillmann waited nervously to buy the rubber stamp and worried that “someone might call police.” The stamp, bearing the name of a Japanese businessman he had never met, was phony--part of a hastily concocted scheme to extract $30 million from Iran using scores of fake invoices that Tillmann had ordered from a local print shop, he now says.

Tillmann’s unusual enterprise, which he insists was done at the behest of higher-ups in the Thyssen-Fluor joint venture, provides an extraordinary glimpse of the pressures that can develop when major corporations have invested hundreds of millions of dollars in an overseas venture--only to see it threatened by political upheaval.

The case also raises questions about the ethical and other responsibilities of senior corporate executives for monitoring and controlling the actions of lower-level managers. And, in this case, years before the Iranian arms-and-hostages scandal, it is Iran that claims to be the victim.

Thyssen, which refused to allow its top executives in Germany to be interviewed, acknowledged in a written statement that bogus billings had taken place. But the West German firm contended that no harm was done, because it was merely obtaining money legitimately owed it under terms of a fixed price contract.

Fluor officials, expressing shock over Thyssen’s admissions about contrived invoices, claim no knowledge of such a scheme. Fluor executives insist that the American company had no part in processing any false bills, despite a claim by Tillmann that Fluor’s top man on the refinery project, James C. Dixon, helped concoct the phony bills. Dixon also denies creating false invoices.

Details of the financial drama behind the oil refinery project--to be built in the Iranian city of Esfahan--emerged from interviews with Tillmann and other corporate sources and from confidential company documents and private investigative reports only recently made available to The Times.

The documents describe a “hectic atmosphere” in the fall of 1978 in which German accountants, allegedly with help from an American project engineer and inside sources at the Iranian oil company, processed $30 million in phony invoices in only two weeks.

False Japanese Invoice

Among the recently discovered telltale documents are a false Japanese Steel Works invoice for $776,412 supposedly authorized by a deputy general manager who had left the company a year before the invoice was dated, and a contrived invoice for 7.6 million French francs drafted under the name of a French construction company whose own books showed that its legitimate invoice of the same number was for only 2,257 francs on an unrelated project.

A former director of the government-controlled National Iranian Oil Co. told The Times that the company, which maintained an account in a Duesseldorf bank to pay Thyssen and Fluor for their services, would not have paid the fake invoices were it not for the chaos of the revolution.

“If the project had been finished before the revolution . . . one of our internal auditors would have caught up with it,” said Majid Diba, a top National Iranian Oil Co. official when the shah was deposed. Because of spreading political unrest, he said, “there was no possibility” of detecting the false documents at the time.

The refinery, which Fluor said was 99.2% complete when the Iranian revolution forced Thyssen and Fluor to abandon it, is now processing oil--reportedly 280,000 barrels a day--for the government of the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

‘Grossly Misleading’

Thyssen’s contention that the bogus billings did no harm because they merely procured funds legitimately owed by the Iranians was labeled “manifestly and grossly misleading” by a three-judge panel in the Hamburg Regional Court, which recently dismissed a libel action brought by Thyssen against the German magazine Der Spiegel. The publication characterized the participants as “a gang of forgers” from highly respected international companies “plundering the treasury of a foreign state.”

Blames Thyssen

Dixon, Fluor’s chief official on the refinery project, laid all the blame for the bogus billings on Thyssen. “These (Thyssen) guys probably did a lot of monkey business,” he said in an interview. “But I was not involved.”

And David S. Tappan Jr., Dixon’s boss as Fluor’s chairman and chief executive officer, said: “I would be absolutely stunned if he did that.”

A Fluor spokesman said that the company is looking into the matter. “At this time,” he said, “we’ve uncovered no wrongdoing by any Fluor employee.”

Tappan said during an interview in Irvine that Iran still owes the company more than $250 million associated with the Esfahan project. But in complex litigation still pending before the Iran-United States Claims Tribune at The Hague, Iran insists that it owes considerably less, in part because of fraudulent billings.

Although Tillmann and his colleagues carried out their scheme more than eight years ago, its aftereffects continue to haunt the participants--straining relations between the corporate giants, ruining careers and jeopardizing long-standing financial claims. Last October a German special prosecutor was assigned to investigate the affair, which one German newspaper called “probably the greatest violation of normal practice in post-war German economic history.”

The Esfahan project began at the height of the world oil crisis in 1975. Iran was undertaking a major industrial development program requiring increased supplies of products that the new refinery would produce, including gasoline, jet fuel, diesel fuel, kerosene, solvents and asphalt.

Although Fluor and Thyssen had been partners on two other successful refinery projects in Tehran for the National Iranian Oil Co., internal Thyssen memoranda say that the Esfahan project encountered problems from the outset. There was, for example, a shortage of skilled workers at Esfahan, which is more than 300 miles from Tehran. And historically high worldwide inflation made cost projections extremely risky.

Meanwhile, opposition to the shah’s regime was growing bolder and more strident.

By the summer of 1978, all those factors were combining to make the Esfahan refinery project one tremendous management pressure-cooker.

Flawed Inflation Data

And the partners faced a still greater problem--the Iranian government’s failure to keep current inflation statistics. Payments in Iranian rials were supposed to be adjusted to reflect the changing value of the currency, but the contractors complained that those adjustments were insufficient because the national economic indicators were chronically out-of-date.

A high-level delegation of Fluor and Thyssen officials--among them Tappan and Tillmann--finally flew to Tehran to negotiate adjustments in the “rial escalation” clause of the refinery contract. It was too late.

“It was obvious things were deteriorating,” Tappan recalled. “What we were trying to do is get the job finished and get our money before the roof caved in.”

He said the shah decided: “There was not going to be any more escalation, so the way to prevent it was to stop issuing the (inflation) index.”

Even while the Fluor-Thyssen delegation was meeting with top officials of the National Iranian Oil Co., the streets outside contained scenes of increasing violence and confrontation. U.S. Embassy officials warned the delegation to leave as soon as possible.

Fluor’s corporate jet was ready to leave before dawn on the morning of Sept. 8, 1978, which became known as “Bloody Friday” because it was the day troops loyal to the shah fired on demonstrators, killing scores of them. But because of an airport curfew, the plane had to wait until 6 a.m.

“I can tell you we were rolling at 6 a.m.,” Tappan recalled. “At 7 a.m. they shut down the city.”

In a pre-dawn taxi ride to the airport that morning, Tillmann and his boss, Heiko Vogler, discussed the unsuccessful negotiations and the political climate that forced their hasty departure.

“Mr. Vogler told me something would have to be done,” Tillmann said.

Furthermore, according to an internal Thyssen report, there was an offer of help from an Iranian oil company insider. The memorandum noted: “Since someone from (the Iranian oil company) agreed to intercept (handle) the unusual invoices, quick acting had become necessary.”

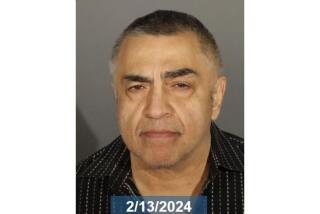

Tillmann, whose 48 years show in his receding, gray-black hair, was a Thyssen accountant on the Esfahan project, an expert on the contract clauses designed to protect the builders from radical inflation swings.

During two days of interviews at a Duesseldorf hotel, practically in the shadow of Thyssen’s gleaming steel skyscraper headquarters, Tillmann said that the strategy adopted in the aftermath of Bloody Friday involved use of the bogus invoices. It was Vogler, Tillmann asserted, who told him that Tillmann’s job depended on his success.

Vogler, like others involved in the scheme, is no longer with Thyssen and declined to discuss his role.

“I’ve been not discussing the subject so far,” Vogler said. “I don’t see much sense in talking about this old story. For me, it’s an uninteresting subject. I cannot be of any help. Neither could I deny or confirm what you have.”

Prepared Confidential Memos

Much of Tillmann’s recollection of the events in September, 1978, was included in extensive confidential memos he was ordered to prepare during an internal investigation by Thyssen executives in 1980. As a consequence, Vogler and Helmut Gschwend, one of the company’s top executives on the refinery project, were forced out of the firm, although Gschwend reportedly still does consulting work for Thyssen.

Tillmann, too, was ultimately discharged in 1983 and said he was now willing to disclose his copies of the internal documents out of anger over that dismissal and a severance settlement that he considers inadequate. He said he also waited to allow the local statute of limitations to expire so that he would not face any legal penalties for his role in the scheme, a fear he said has haunted him since 1978.

“I was living for years on a bomb, really,” Tillmann said. “I feared the whole time that I might go to jail, and that’s the absolute end for a person’s career--for life.”

According to the Tillmann interviews and his reports to Thyssen executives, the bogus invoices were created soon after the Fluor-Thyssen delegation returned from Tehran. Tillmann went through the refinery project ledgers to find the names of suppliers who had submitted substantial bills in the past. Then, during nights and weekends, when Thyssen project offices were virtually deserted, Tillmann typed up the phony bills.

“I was in a position where I could not say no,” Tillmann said. “If I had not done this, there was not the slightest chance to stay” with the firm.

One of those who “personally helped,” Tillmann advised his superiors in 1980, was Dixon, Fluor’s refinery project manager. Tillmann told The Times that the project manager’s help was critical because Tillmann lacked the technical expertise and facility with English to draw up invoices that would pass muster at the bank.

Changed Typewriter Balls

Tillmann said Dixon wrote 10 to 15 “texts” for the invoices that Tillmann later copied on an IBM electric typewriter from Dixon’s handwritten notes. “Just so not to have the same typing,” Tillmann said, he bought six different type-face balls and changed them from one document to the next.

Dixon said he did not assist Tillmann in drawing up invoices.

The 64-year-old Dixon, who has scaled back his duties to part-time consulting work for Fluor, said in an interview outside his Newport Beach home that he had met with Thyssen officials, but not Tillmann, during that time. He also remembered “brainstorming ways to get the (joint venture’s) money out” with them.

“Thyssen people were trying to screw people out of money,” Dixon said in the first of two interviews. He cited what he said were efforts by Thyssen to avoid paying German and Iranian taxes on some proceeds from the refinery project.

A handwriting expert consulted by The Times concluded, based on limited handwriting samples, that the drafts of the invoices appeared to be drawn in Dixon’s hand. The expert reached his conclusion by comparing the handwriting on the drafts with Dixon’s signature and wording on his Orange County voter registration form.

However, when given copies of the invoice drafts attributed to him by Tillmann, Dixon said they “look contrived . . . to the discerning eye.” He suggested that someone at Thyssen may have done “some creative things with a Xerox machine.”

“Thyssen has a lot of my handwriting samples. I did a lot of work for them,” Dixon said. “I did not write those.”

Dixon also said it would have been unlikely for him to deal with a Thyssen official of such modest rank as Tillmann. He confirmed, however, that Tillmann had been a guest in his home while the Esfahan project was under way.

“Frankly, Fluor tried to stay as lily-white as we could,” Dixon added. “We insisted on staying that way--and we did.”

Indeed, Thyssen’s own internal investigative documents note that “Fluor repeatedly voiced that any actions outside the law cannot be expected from American employees,” thus putting Thyssen “more and more on the spot.”

Regardless of who prepared them, the fake invoices were designed to look very similar to bills being submitted routinely to Duesseldorf’s Deutsche Bank, which administered $30 million remaining under a letter of credit authorized by the National Iranian Oil Co. On receipt of invoices for services and supplies, the bank would transfer funds from the oil company account to the Fluor-Thyssen joint venture account managed by Thyssen.

Fluor received some payments from the account in compensation for its engineering and construction work. The exact amount is not known.

According to Tillmann’s 1980 report to Thyssen management, bank officials expressed some concern about the sudden increase in costly billings between late September and the middle of October, but took no action to verify the documents.

“A customer as highly esteemed as Thyssen would not be doubted,” a German bank official who asked not to be identified told The Times. “We would never have believed they would have forged documents.”

Some of the counterfeit invoices include:

--A Japan Steel Works Ltd. invoice asking for payment of $776,412 for overtime premium “recently approved by Fluor Thyssen representatives in Duesseldorf.” The invoice, dated Sept. 28, 1978, was signed by Toshiyuki Okubo, deputy general manager in the sales administration department of the Japanese firm.

Earlier Retirement Cited

However, in a telex last summer, the Japanese steel firm advised the National Iranian Oil Co. that Okubo had retired on Sept. 23, 1977, a year before the phony invoice was issued. “Invoices prepared by us during Aug.-Sep./1978 are impossible to have Mr. Okubo’s signature because of his retirement,” the telex said.

--Invoice No. 68621, ostensibly from Constructions Metalliques de Provence, a French construction company, seeking payment of 7.6 million francs for “early delivery of plates and accoutrements required for the early construction of tankage.” Dated Oct. 11, 1978, it noted in English that the bill was “for the Fluor Thyssen Joint Venture Isfahan (sic) Project.”

However, the French company’s records show that the real invoice No. 68621 “concerns an affair totally different.” The real invoice, unrelated to the refinery project, was for only 2,257 francs and was submitted to a French chemical company on Oct. 19, 1978.

Although Thyssen declined to meet with Times reporters in Germany, the company provided a two-page response to the request saying that its “method of providing invoices” had not been challenged by the National Iranian Oil Co. Thyssen said the funds realized through the billing process were used to pay 2,000 Iranian workers on the project.

Nevertheless, Thyssen executive Peter Wiede said in the written response: “Soon after the Thyssen management became aware of the methods of invoicing, the responsible employees left the company.”

‘Embarrassing as Hell’

Fluor’s Tappan admitted that reports about phony invoices were “embarrassing as hell” but said he was certain that if such tactics were used, it would have been with the “full cooperation” of the Iranians. He also said that his company knew nothing about the invoices and was never informed about the internal Thyssen probe.

“I would say that this is not something that was our direct responsibility, or even indirectly,” Tappan said. “(But) it’s certainly uninspiring to have this develop for whatever fact or fiction is involved in it.”

He insisted that Fluor aggressively enforces ethical standards of business conduct. “Any unethical activity that anybody did would be stomped on,” he added, “I can tell you that.”

While denying that the bogus bills were the determining factor, he said he doubted that Fluor would enter into any more joint ventures with Thyssen.

A key whistle-blower in the allegations of fraudulent invoices has been Abolfath Mahvi. He is a wealthy Iranian businessman who says Thyssen and Fluor have failed to pay him the money he contends he was promised for convincing the shah and the National Iranian Oil Co. that the joint venture should build the refinery.

Lawyers for Mahvi, who has been involved in litigation with Thyssen and Fluor, helped gather documents that supported the allegations. Fluor contends Mahvi, who now lives in Geneva, has “set out to embarrass” the company. The two companies contend they do not owe Mahvi the percentage he insists is due him.

Dixon provided a dramatic example of the importance the refinery builders attached to recovering their funds from revolution-torn Iran, a recollection of risking his life in a futile effort.

Flew Back to Tehran

In March, 1980, three months after Iran’s new regime began holding 52 American hostages, Dixon flew back to Tehran to resolve the funding disputes that had suspended refinery construction. The effort failed, and Dixon went to Tehran’s airport, hoping to board a westbound plane.

At the airport, Iranian officials separated him from other travelers and began to question his passport and authority to travel.

An Iranian woman, being held in a detention area with Dixon, realized he was an American and asked, as Dixon recalled: “Are you crazy?”

Only when he quietly arranged with a Thyssen executive who also was at the airport to create a disturbance was Dixon able to get by a distracted emigration official and escape the country.

Recalled Tappan: “I remember the trip and I remember holding our breath.” He called Dixon “extremely courageous” and said: “I’m sure his life was in jeopardy throughout that visit.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.