Students Have Fun in Process of Learning : Math Humorist’s Teaching Adds Up to Giggles

- Share via

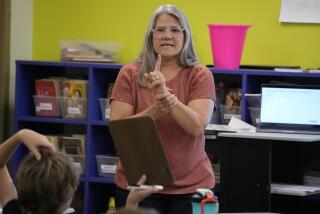

There was something strange about this particular mathematics lesson. The students were laughing and actually seemed to be enjoying themselves.

Over math?

Meet Paul Oliverio, math humorist.

Teacher, too. But Paul Oliverio has this notion that teaching--and learning--math can be fun, so he takes his math gig on the road and teaches math--specifically, geometry--on stage.

This particular day he was at the Christ the King Academy, a small, private nondenominational Christian school in Fallbrook, and he stood in front of 45 kids.

Plays the ‘Godfather’

He introduced himself with an exaggerated Italian accent as the “Godfather of the Parallelo family,” and selected three students to play his sons.

The names given them were Rectango, Squarini and Rhombo, and they were debating the size of their territory, the story line goes. Rectango wants his territory’s boundary to include a right angle--so he gets four. Squarini likes right angles, too, but he’s a product of a liberal arts education and believes in equal rights, so he argues for the sides of his territory to be of equal length. He gets it. Rhombo, the black sheep of the family who seems headed for a career as a diamond smuggler, gets his territory shaped like one, a rhombus.

There are a lot of one-liners thrown in along the way (“A right angle is 90 degrees? Wow, that’s hot. Four of them are 360 degrees? Wow, you can cook a pizza in that one!”) The kids giggle and laugh, and when Oliverio’s 15 minutes on stage is over, they applaud. And they probably will never forget the properties of a rectangle, square and rhombus.

School principal Pat Savas was delighted by the performance, however corny.

‘Make It Fun’

“So many of us see math as a great onus, so anything we can do to make it fun and enjoyable, versus a burden to get through, is great,” she said.

Oliverio may be more extreme than most math teachers in his approach, but he reflects a growing trend among educators to come up with new ways to teach math, and to focus not on rote memorizing of math rules and equations but on understanding the dynamics of math.

Two plus two is still four, but instead of looking at the numbers on a sheet of paper, kindergarteners are counting four buttons or four toothpicks or four building blocks.

Two times three is still six, but primary-grade students look at three people with two ears each, or two legs, or two eyes, to come up with the answer six.

Avoiding Rote Method

“We’re definitely trying to get away from rote memorization because it appears that hasn’t worked for the general population,” said Janet Trentacosta, mathematics coordinator for the San Diego Unified School District. “Now, we’re working more with manipulatives--actual concrete models (such as toothpicks, buttons, etc.) to show students the concept of what we’re trying to teach.

“Rather than having our students memorize the fact that four plus five is nine, we’re finding it’s far more beneficial to show them four objects and five objects and have them put them together and realize there are then nine objects. It’s concrete. They can see it.”

And they’ll remember it.

It’s a simple concept in teaching--trying to move from the abstract, which generates anxiety, to the concrete--but it has been a long time coming in math and the advancement is critical in helping young children get a better grasp of what may be America’s most feared classroom subject, experts say.

“We should always have been doing it this way,” Trentacosta said. “The days are gone when we sat there obediently in the classroom and memorized what the teacher said. Now, we have students living in the generation of TV and video; it’s a very exciting world, and kids don’t want to just memorize anymore.”

Must Understand Why

The new buzz phrase in math is “teaching for understanding,” she said. It’s no longer good enough for a student to know that two plus two is four; now he must understand why the answer is four.

To that point, the state Board of Education several months ago rejected virtually every mathematics book submitted for its approval, sending them back to the publishers with orders that they develop better concepts of understanding math versus the old-fashioned rote teaching of principles.

“Mathematics research has told us all along that we’ve needed to do this,” Trentacosta said. “What has finally really pushed us in this direction is all the studies that compare us to other countries (in math skills) which show us declining.

“We’ve just completed the back-to-basics movement, and we still aren’t any better at it. Our children need to better understand, not just know, the answers.”

For that reason, she said, calculators generally are now allowed at levels as early as sixth grade for tedious computational problems. “We are teaching students how to use the calculator, the power of the calculator, as part of the math curriculum,” she said, “because it’s more important to understand how to solve the problem than to come up with the right computation itself.”

‘Keep It Exciting’

The challenge in teaching math, Trentacosta said, “is to keep it fresh and exciting. Math won’t necessarily become easy for all students, but it certainly can be exciting and fun. And any teacher who tries to use more than just paper and pencil, and involves the other senses, to get students to learn is certainly on the right track.”

Enter Oliverio, who lives in Vista. A self-described math prodigy (“Instead of counting sheep at night, I counted factors of two up to eight digits”), Oliverio, 37, is a “math free-lancer.” He works occasionally as a substitute math teacher in San Diego and Orange counties but admits that he has little use for school administrations and would rather work directly with students and parents. Most of his work is as a tutor, and his road show on the “Parallelo family” is for hire.

He said students get off on the wrong foot when they are confronted with math “word problems.”

“Just the use of the word problems creates anxiety,” he said. His simple solution: Call them “math mysteries,” with the goal of finding a solution “for Mr. X.”

Students Understand

He takes a page from Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland” by suggesting that some algebraic equations be treated “through the looking glass.” If a student is asked to solve the equation, “X plus five equals nine,” consider the equal sign to be the looking glass which reverses everything; send the “plus five” through it, and the equation then becomes “X equals nine minus five.” It is then easier for the student to understand the problem and solve it, Oliverio contends.

Gimmicks like that, he said, “have to be done carefully and selectively. I’ve gone into math classrooms as a substitute and tried to teach them the ‘looking glass’ approach to solving algebra, and they couldn’t catch on because they had been taught a different way and I was confusing them, so I dropped it.”

But the goal of the teacher remains, he said, to make math less intimidating.

“Math concepts might be quite simple, actually. What we have to do is communicate those concepts without fear and anxiety, and that’s not always simple.”