Retrained for Air-Conditioning Job : New Work Clothes Suit Ex-Steelworker Fine

- Share via

ST. PETERSBURG, Fla. — “I got him!”

C. Norman Morrow III slams the door shut on his jet-black Camaro, wipes the thick Florida summer sweat from his forehead, peels out of the sand-covered construction site and finally smiles for the first time in an hour.

“You know how I could tell? He started using my line. He started saying he didn’t want to put Volkswagen engines in Cadillac bodies. That’s my line that I developed. When he started saying my line back to me, I had him won over.”

He exhales. “The hard life of a salesman. Eh? What do you think?”

It has indeed been a tough morning in the life of this salesman. Morrow, a pale, thin redhead only a year removed from the very different life of a steel mill hand in Clairton, Pa., has spent the last hour struggling through the thick sand and brutal heat of a suburban construction site, worried that he may be on the verge of a major setback with his first big customer.

“I’ve lost him, I can tell,” he said quietly early in the morning. “This is what you call a crisis before lunch.”

Behind Schedule

Installation of the air-conditioning system Morrow designed and sold to the builder for one of the 120 homes in this development is behind schedule, holding up work on the house; a laborer for Morrow’s firm has quit without notice. The delay may mean that Morrow will get shut out from bidding on the rest.

But Morrow takes the offensive. He trails through the remnants of the piney woods where $200,000 houses are rapidly going up. He cajoles the contractor, letting him know that he cannot get better equipment or service from his other air-conditioning supplier. With his rapid-fire banter switched onto automatic, he successfully changes the subject from the construction delay, points out the drawbacks of the system being installed by a competitor in a neighboring house in the develop ment and gets the builder talking in his terms.

Finally comes the grabber. You’ve got Cadillac homes, he tells his client, so don’t put Volkswagen air-conditioning systems in them.

“I think I worked my way out of that one,” he says as he drives back to the office. “You notice how I talked real fast?” He laughs. “You can’t let them get a word in. . . . My friends in school used to tell me I could sell anything.”

Talking your way out of tight spots. Wearing a tie. And above all, keeping your hands clean at work. For a man who has spent his entire adult life up to this point either in a “rust belt” steel mill or on layoff from one, a niche in the Sun Belt service economy--designing and selling air-conditioning systems for new homes--is heaven.

Rich Potential

In fact, it seems that 30-year-old Norman Morrow, a newly minted sales engineer making $32,000 a year at Airtron Inc., has finally found his rightful place in the world, tapping into the rich vein of salesmanship potential that was undoubtedly lurking underneath his blue collar during all those years at United States Steel Corp.

“In the mill, I worked eight hours, and I did the same thing day after day after day. I stood on top of coke ovens that were so hot we had to wear wooden shoes. I always knew what I was going to do, and how much I was going to get paid for eight hours’ work. Two years after I started, I was doing the highest paid production job in the mill. That was as far as I could go, and I was already there in two years.

“But here, the only one holding me back is me. Back in the mill, we used to joke we were going to do eight hours’ work for eight hours’ pay. That was a joke to us. We wouldn’t work that hard. But here, they didn’t get the joke.”

Uncertain Future

But even with his quick mind and quicker tongue, it’s still hard for Morrow to grasp how rapidly his life has changed, how he has suddenly been thrust into the middle of a huge out-migration from the industrial heartland, an exodus from America’s economic and social past to an uncertain future.

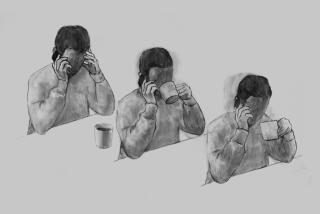

“I’d just like to sit down and take a deep breath one time.”

Over the past year, Morrow has been rudely thrown out of his job at U.S. Steel, and has been forced, in effect, to recycle himself. He has had to adjust to an office environment for the first time in his life, to clean up his mill-hand language (although his occasional double negatives still betray his roots) and to act like a professional.

He and his wife, Kathiann, have left family and friends behind. They are still making payments on a house they cannot sell in one of the tiny steel towns that dot western Pennsylvania’s desperate Monongahela Valley. And Kathiann Morrow is expecting their first child any minute. (Soon after this workday, their son, Justin Andrew Morrow, will be born.)

Used His Wits

Norman Morrow is coping, probably better than most of the hundreds of thousands of other rust belt workers displaced by imports. He has used his wits.

But it was not too long ago that he seemed on the verge of becoming yet another depressingly familiar economic statistic. When he graduated from Elizabeth/Forward High School in Elizabeth Township, Pa., in 1975, Morrow did what generations of “Mon Valley” men had done before him--he followed his dad into the mill. Soon, as a laborer at U.S. Steel’s Clairton coke plant, he was working alongside his father--who had unsuccessfully urged him to get an education--and was making more money at 19 than the teachers he had just left behind in high school.

“My first year in the mill in 1975, I made $25,000. That’s why I didn’t go to college.”

At 21, he was married, had a house and two cars and had become a full-fledged member of America’s blue-collar elite.

Doors Shut Tight

But he was the last. The doors into the mill shut tight behind him. As the steel industry slid into oblivion in the late 1970s and early 1980s, his three younger brothers found that they could not get hired. They have since been forced to scrounge for maintenance and construction work, or seasonal jobs with lawn-care companies. “We were at the end of the boom years. Guys in my class were the last to go right from school into the mill.”

Finally, as foreign steel poured in and the domestic steel industry nose-dived into a depression, Morrow found himself out on the street too. He was laid off in January, 1982, and would not get back into the mill for four dark years.

He never thought it would last so long, so he partied for months, took it easy with his unemployed friends, stayed out late. He was living off his wife’s income--she had a data processing job--and his marriage was foundering.

“My wife put up with a lot from me,” he acknowledges.

“I don’t actually think it was close enough to think about it (divorce) seriously,” Kathiann Morrow says. “But as the time wore on he got more depressed. It has something to do with you not working and your wife supporting you.

“We did a lot of fighting, and I maybe threw it (divorce) up once in a while.”

Retraining Program

A friend saved him. He told Morrow about a new retraining program for displaced steelworkers that offered to pay his tuition at a local community college. When Morrow said he was not interested, his friend came around to pick him up for the start of school anyway. “I thank him every day,” Morrow says.

Convinced, Morrow took technical courses in energy management and air-conditioning systems and emerged 2 1/2 years later with an associate degree and new ambitions.

Still, he could not break completely with his past. Even after he graduated, when the mill called early last year, he jumped.

But when he did go back, after college and four years away from steel, Morrow no longer felt like a mill hand. For the first time, he looked at his future, and he did not like it. He could not stand the thought of 30 years as a “lidman” on top of a coke oven.

Finally, U.S. Steel (since renamed USX Corp.) made up his mind for him. Just four months after he was recalled to work, Morrow was laid off again, and this time he could read the handwriting on the steel mill wall.

‘Employee No. 11644’

“Realism set in,” he says. “When I went back, I knew that was not the job for me anymore. I looked at people different that time. I thought I was better, better than I was before; I felt more intelligent. I didn’t want to go back into that repetitive feel again. I didn’t want to be just employee No. 11644 again. So getting laid off again was the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

Last June, with the help of a company-funded job assistance center for laid-off steelworkers, he found work and left for Florida for good. He made some false starts in the Tampa Bay area--he quit his first job when his struggling employer failed to pay him, and later failed at an attempt to start his own business. But last February, Morrow hooked up with the suburban Clearwater office of Airtron, a large air-conditioning retailer.

Although he still misses the rest of his family, Morrow is finally settling down: selling and designing air-conditioning systems by day, going to technical school at night. His wife, who has wanted children since their marriage nine years ago, is happy and “loves Florida.” And, although his father has told Morrow that he is likely to be called back to the mill again by December, this time he is going to refuse.

Not Steelworker Anymore

Norman Morrow is not a steelworker anymore.

“He acts different now,” Kathiann Morrow says. “I think it’s because of the people he’s around. He acts more professional. His conversations are different. Before, he just went to work. Now he works towards a goal. He has more of a positive attitude.”

After lunch, Norman Morrow is back on the road again, his morning mini-crisis almost forgotten. “Cold calls” are the order of the afternoon--a new salesman just learning his territory has to put in plenty of legwork.

Morrow does not find it tedious; it gives him a freedom on the job that he has never before experienced. “And it’s not like I have to put in long days on the road. I just do short jaunts, pull over and talk to a builder. So I never get lonely.”

Driving around a subdivision full of mansions under construction on some of Tampa Bay’s most exclusive waterfront property, Morrow studies the newest projects to see if air-conditioning contracts have been awarded by the builders. He checks in with one potential customer who is already studying his bid. He will find out the next day that he has won the work on at least two more houses. Morrow’s bosses are quietly impressed.

‘He’ll Be Fine’

“He’s surprised me,” says Roger Rawleigh, vice president and manager of Airtron’s Clearwater office. “It usually takes five or six months before we expect a salesman to be productive, but he’s ahead of that pace. As long as he maintains his attitude, he’ll be fine. Desire’s the only thing it takes in sales.”

Back at his desk and drafting table late in the afternoon, Morrow seems intent on making it. He knows he has been given a rare second chance to get out of a blue-collar life, and he plans to make the most of it.

And, although he is still only earning about as much as he did in the mill, Morrow is positive that he will hit it big once he goes off straight salary and starts getting sales commissions.

“It’s very possible here to sell a million dollars’ worth of equipment a year,” Morrow notes in wonder as he sits at his drafting board, modifying blueprints and pricing estimates to satisfy a customer.

Morrow repeats one of his favorite lines: “I’m the only one holding me back.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.