Archeologists Gain New Respect for Ancient Bolivians

- Share via

LUQURMATA, Bolivia — U.S. archeologists are unearthing evidence that Bolivia’s ancient, enigmatic Tiwanaku culture was a powerful empire that supported tens of thousands of people in its central city and immediate suburbs.

Digs in this peasant village on the swampy edge of Lake Titicaca are turning up an extensive network of terraced, stone-walled houses and courtyards dotted with tombs, some containing elaborately crafted ceramic bowls and figurines dating back more than 1,000 years.

“Almost every time we’ve put a hole in a two-kilometer-square area, we’ve hit a house,” said Charles (Chip) Stanish, an anthropologist at the University of Chicago. “We not only hit one house, we hit a lot of them.

“It’s becoming clear we’re looking at massive population sites.”

To Bolivians the discovery is not that surprising. For decades they have maintained that the Tiwanakus were once the Americas’ finest and most powerful empire, providing the inspiration for the better-known and relatively modern Incas of Peru.

But the digs are destroying a notion long held in international archeological circles that the culture was little more than a loosely knit confederation of fiefdoms struggling to survive in the thin air, harsh climate and infertile soil of the Bolivian altiplano (high plains), about 13,000 feet above sea level.

“It’s now being considered a powerful, integrated state,” said Alan Kolata, an anthropologist from the University of Illinois who is co-directing the excavations with Bolivian archeologist Osvaldo Rivera. They are the first major foreign digs in Bolivia since the 1930s.

Emerging shortly before the time of Christ, the Tiwanakus flourished for scores of generations and reached their technological and artistic peak in the years AD 600 to AD 800, before the culture collapsed and disappeared about 400 years later. Their influence extended north and west across Lake Titicaca well into Peru, east into the rain forests of the Amazon Basin and south into Chile and Argentina.

Their central temple stood at what is now the potato farming village of Tiwanaku, 10 miles from Luqurmata, which apparently was a vital suburb. Still standing are a haunting collection of massive stone ruins, including an accurate calendar and an elaborately carved Gateway to the Sun.

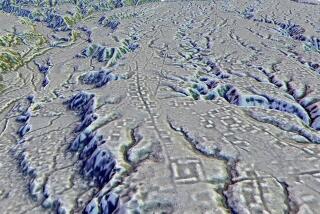

Also left behind, at points all around the lake and even hundreds of miles from it, are a now-disintegrating network of raised fields that provide the basis for arguments that the Tiwanakus had the resources for a concentrated population and wide-ranging political control.

Excavations have shown that the fields, divided by long irrigation canals, were sophisticated and highly productive. A base of cobblestone was topped by gravel and then impermeable clay, which kept salt from the lake’s brackish waters from seeping into the topsoil above.

Recent studies across the lake in Peru by Clark Erickson, also of the University of Illinois, indicate that productivity was as much as 800% that of current farming practices.

Kolata holds a more conservative estimate of 300% to 400%, but nonetheless believes that the fields could easily have supported 40,000 to 120,000 people alone in the 32-square-mile Tiwanaku valley. “That’s a substantial population, by any standard,” he said.

Both he and Erickson are engaged in projects to put the raised-field technique back into practice. A few experimental fields have been started with enthusiastic support from local authorities, who see this “applied archeology” as a means to improve the standard of living for the area’s poor farmers.

“It’s a rescue of lost technology, and of the values of the past,” said Rivera, planning chief of Bolivia’s Institute of Archeology.

Few details of the Tiwanakus’ life and religious practices are known, in large part because few modern excavations have been conducted since the American Wendell Bennett in the mid-1930s. Angered by the loss of invaluable artifacts, carried off to museums or private collections in the United States and Europe, Bolivian authorities barred foreigners from any major excavations for half a century and had little money to conduct their own investigations.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.