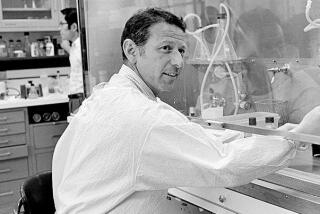

Noted British Essayist and Lecturer : Sir Peter Medawar; Nobelist in Medicine

- Share via

Sir Peter B. Medawar, a British scientist and essayist who shared the Nobel Prize for medicine for his research on the body’s rejection of tissue transplants, is dead.

The British news media reported over the weekend that Medawar had died Friday night in London’s Royal Free Hospital. He was 72 and the Press Assn., the domestic British news agency, said he had suffered a series of strokes and had been in a coma for several days.

In addition to his scientific achievements, Medawar was also known as a pithy lecturer and writer who maintained that it was science and not religion that had given modern man a realistic feeling of the sanctity of human life.

There are no wicked scientists, he would tell audiences--delighting in their discomfort which soon turned to amusement--but there are “plenty of wicked philosophers, wicked priests and wicked politicians.” And, he would add, any evil science might do came only from its desire to do good.

In his written works, such as “The Limits of Science,” published in 1984, Medawar said that “quite ordinary people can be good at science” and “to say this is not to depreciate science but to appreciate ordinary people.”

In his autobiography, “Memoir of a Thinking Radish,” published last year, Medawar discussed his early, often esoteric research and argued that scientists who perform experiments may be “unhappy, strangely mixed up or comic, but not in ways that tell us anything special about the nature or direction of their work.”

Defending those experiments, which seldom led anywhere, he said, “I don’t regard my own messings-about as any more discreditable than those of a writer who, before writing the novel or play which makes his reputation, spends his time on potboilers and half-finished manuscripts.”

Efforts Led to Nobel Prize

The “novel” that established Medawar’s pre-eminence came in conjunction with the labors of Sir Frank MacFarlane Burnet of Melbourne University in Australia.

Their efforts, which were to lead to the 1960 Nobel Prize, established that a human form, since the day of its conception, develops the ability to recognize its own tissues. But if foreign tissues are introduced during the embryonic stage, the body will be able to recognize and tolerate them later in life.

That breakthrough came after Medawar had been asked by Britain’s Medical Research Council to determine why badly burned World War II casualties were rejecting skin grafts.

Burnet had begun the research in 1949 and developed the theory of rejection while Medawar’s work confirmed his findings.

After Medawar’s findings were published it was established that tolerance to donor grafts could be developed.

The two men also proved that newborn animals could accept material injected into them from other animals immediately after birth and before the immune system had time to mature.

Medawar, born in Rio de Janeiro where his parents were in business, attended Marlborough College, where he said a biology instructor first interested him in science, and then earned a degree in zoology from Oxford. After the war he taught at the University of Birmingham and University College, London, and from 1962 to 1971 headed the National Institute of Medical Research.

Despite his teaching and research, he found time for writing and his books ranged from “Advice to a Young Scientist” to “Aristotle to Zoos, a Philosophical Dictionary of Biology.”

In the late 1950s and early ‘60s he became moderately famous for a series of lectures on “The Future of Man.”

He was knighted in 1965 and in 1981 received the Order of Merit, the most prestigious of all royal honors. The order is a small, select group which the reigning British monarch chooses personally.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.