Bhopal and the Export of Danger : THE BHOPAL SYNDROME <i> by David Weir (Sierra Club Books: $17.95; 224 pp.) </i>

- Share via

It’s been three years since the Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal, India, released deadly methyl isocynate (MIC) gas in the middle of the night. More than 2,500 people died in that disaster, and 17,000 were permanently disabled, according to David Weir. Since that event, the nuclear reactor in Chernobyl exposed millions of people to radiation. Closer to home, not a year has passed when a fire, a leak or a rail or traffic accident hasn’t exposed Americans in one community or another to dangerous poisons. Weir proposes that these, and many other threats to public health, are symptoms of a “Bhopal Syndrome.”

It’s conventional wisdom that industrial safety standards in the Third World are far below those of the West, that a Bhopal disaster would not happen in the United States because regulation and inspection would not have permitted such a dangerous condition to develop. Conversely, the developed world, through multinational corporations, has transferred dangerous production to nations that cannot afford to decline them and lack an effective means of enforcing safe conditions. As Weir observes dryly, some of the multinationals have larger budgets than their host countries. He provides several examples of “other Bhopals” in the making, including a DDT plant in Cicadas, Indonesia, that seems to make the locals sick, the Bayer industrial complex about 20 miles from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, sited along a river that no longer has fish, and Taiwan, where there are numerous pesticide plants directly adjacent to dense human populations.

The Third World issue is only part of Weir’s syndrome. In developed countries, industrial secrecy is used to deny information to neighbors about what materials their plant is producing and how it is stored, transported and protected. Governments themselves don’t tell the full story, to avoid unwarranted alarm or to avoid charges of complicity. Total security, says the industries, is impossible in a world so dependent on many exotic and hazardous materials.

The punch line of this polemic is fuzzy, but it suggests that people are not so dependent upon these dangerous materials as are the multinationals hooked on making them; and that with a more sophisticated assessment of risks and benefits, societies would elect to cut their use of agricultural pesticides--the key players in Weir’s book--and enforce greater restrictions on their manufacture and use.

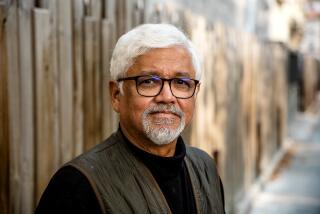

Weir is executive director of the Center for Investigative Reporting in San Francisco, author of another well-known book on pesticides, “Circle of Poison,” and has contributed to a number of national magazines. But there is nothing notably original or radical in his inquiry. The few potential Bhopals he describes are in themselves hardly evidence of a global threat, and Weir’s solutions are limited and vague. As an introduction to a real problem of enormous magnitude, “The Bhopal Syndrome” is palatable reading, but it is not a comprehensive treatment.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.