Science/Medicine : Researchers Successfully Insert Gene Into Blood Cell : Scientists Hope Technique Could Be Used to Correct Potentially Fatal Anemia

- Share via

NEW YORK — A human gene inserted into mice has been shown to work almost exclusively in red blood cells, an important boost for prospects of curing human diseases by replacing defective genes, scientists say.

The study is the first demonstration that a gene inserted into an animal after its birth could be made to work significantly only in the proper bodily tissues, scientists said.

The gene in the study may someday be used to correct a potentially fatal anemia called beta thalassemia. Scientists now must see if genes affecting other diseases can perform in the mouse, said Elaine Dzierzak of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Mass.

But she stressed much more research is needed before the work can be applied to humans.

She reported the experiments in last week’s issue of the British journal Nature with Richard Mulligan of Whitehead and Thalia Papayannopoulou of the University of Washington in Seattle.

“This is a major step forward for gene therapy,” said W. French Anderson, chief of the molecular hematology laboratory at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

The regulatory system that turns the “beta globin” gene on or off in various tissues is complex, he said, and the new work “really moves the whole field forward” by showing the gene could be made to work significantly only in the proper tissues.

Gene therapy is being pursued as a way to correct some illnesses that stem from defective genes. Such genes can prevent production of important substances in the body, or make those substances faulty. The therapy would involve giving patients normal versions of the defective gene.

Scientists want the inserted genes to be active only in tissues where their substances are needed, because an active gene might cause serious harm in the wrong tissues.

Researchers have gotten genes to work only in the right tissues when they injected the genes into fertilized eggs. But the new study inserted the gene after birth, which is closer to the situation that gene therapy would face.

The beta globin gene lets red blood cells make part of the hemoglobin molecule, which in turn transports oxygen from lungs to the rest of the body. A defect in this gene leads to beta thalassemia.

About 100,000 cases of that disease are reported each year around the world, chiefly in Mediterranean areas. Treatment requires regular blood transfusions and other therapy throughout the victim’s life.

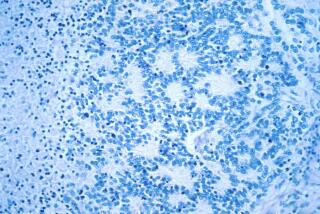

Researchers inserted the human beta globin gene into the genes of a virus, then let the virus infect bone marrow cells from mice. The infection added the beta globin gene to those of the marrow cells.

The cells were then injected in 108 mice. Later tests found evidence that 18 of the mice had the human gene in their marrow.

In eight mice selected for closer study, researchers found that red blood cells derived from the marrow cells were making the protein called for by the gene.

Other kinds of cells that came from the bone marrow did not make significant amounts of the protein, showing that the gene’s own “on-off” switches were enough to activate it in the proper cells.

The red cells were making protein four to nine months after the marrow cells were injected, showing the gene was working stably, said researcher Dzierzak.