Book Review : Tortured Tale From the Vienna Woods

- Share via

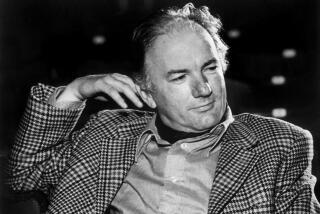

Woodcutters by Thomas Bernhard; translated from the German by David McClintock (Alfred A. Knopf: $15.95; 163 pages).

We surmise that the narrator of Thomas Bernhard’s obsessive dinner-table monologue had a candle once and that it went out. For 163 pages, he curses the darkness.

Mostly, our Western tradition has favored candle-lighting over darkness-cursing. Despair, though a theme, was rarely the leading theme. Along the frontiers of our inveterately hopeful culture, things have been different. In Haiti, for example, a Creole proverb advises us: “If you can’t eat from a plate of soup, you can always spit in it.”

Bernhard, one of Austria’s leading writers, has made a kind of Haiti out of the extinguished pride and display of what was once the heart of the Holy Roman Empire. His Vienna is not merely the end of the West’s road, its cul-de-sac, but a kind of final pit where the denizens, like trapped rats, chew at each other.

“Woodcutters” is Bernhard’s latest chewing bout. The narrator, a writer who has returned to Vienna after living abroad, goes to a dinner at the home of former friends who ran and still run a kind of artistic salon. His monologue, spanning the entire evening, is a diatribe--unspoken except to us--against the city, its intellectual life, his friends and even the dinner, which is “revolting.”

None of the almost non-existent events of the evening and none of the people present are referred to or described without an avalanche of abuse. “Ridiculous,” “contemptible,” “vile,” “stupid,” “vicious” are repeated over and over. The narrator’s voice is a skewed bagpipe, the chanter almost entirely drowned out by the drone.

Intermittently, the narrator gives us a sketchy idea of his life. Coming to Vienna from the country as a young man, he was taken in by a woman writer who became his lover and who introduced him into the city’s artistic circles. The woman, older and now a literary rival, is at the dinner; the narrator reviles her relentlessly.

The narrator’s voice simulates a shrill and bitter energy. He seems to crow as he tells us that Vienna and the friends he once believed in are dead--morally, spiritually and aesthetically. His escape abroad saved him for what he calls--without ever defining it--greatness. To stay in Vienna’s ingrown, backbiting artistic community is to be a failure.

But the voice betrays him. Incessantly, he repeats phrases. As many as five times on a single page, he locates himself sitting apart from the company, silent and in his “wing chair.” Far from being the sole free and critical spirit, he is the most inert of any of them; the most hopelessly caught in the stagnation he decries.

There are hints of this throughout. In the middle of his tirade, he will suddenly praise his host as an extraordinary musician and in the next breath call him a mediocrity. He will evoke flashes of bygone beauty and pleasure, immediately interring them in a new flood of abuse. And bit by bit, he springs his trap upon himself. He says goodby to his hosts, and we realize that, until that point, we have heard him communing only with himself. And what does he now pronounce? A series of effusive compliments, the kind he has been mocking all along. His bitter aloofness is an illusion; he is one of the company.

There is no irony in it. He speaks with enthusiasm, even with ardor. It is an abrupt reversal, and startlingly effective.

Unfortunately, we have had to wait to get to it. And the voice we have attended to all along is so monotonous, so leaden, that it becomes a perpetual chastisement of the reader. The existential monologue, used so well by Albert Camus, can work only if it seems, in its solitude, to question us.

Bernhard’s narrator is isolated past questioning. It is not that he speaks of the world around him as a dream; it is also a dream in Camus’ “The Fall.” But here the dream seems to rise out of sour wine and a heavy meal, and the breath stinks.