Government Pressured to Ease Restrictions : Czech Religious Drive Gains Force

- Share via

PRAGUE, Czechoslovakia — A religious revival that in recent years has been spreading slowly but steadily through Czechoslovakia seems to be gathering force and putting increased pressure on the authorities to ease their longstanding repression of the Roman Catholic Church.

A team of Vatican negotiators has been meeting with government officials here this week in an effort to end a 15-year impasse over the appointment of bishops. There are 13 bishoprics in the country, and 11 of them are vacant. The last appointments were in 1973.

There is no separation of church and state in Czechoslovakia. Under law, the state has the authority to approve or reject the appointment of leading church officials and even to license priests.

Under this arrangement, religious orders have been banned, a seminary has been closed and enrollment at the two remaining institutions strictly controlled. Priests who are considered too active, or whose activities are considered undesirable, are required to surrender their licenses and are forbidden to conduct public services.

Religious Education Limits

There are strict limitations on religious education for children. The formation of lay organizations within the church and the development of an independent religious press have been prevented.

Despite these strictures--because of them, in the view of some church figures--church enrollment has been growing. Underground religious activity seems to be on the upswing as well. There are 9.9 million Roman Catholics in Czechoslovakia, about 60% of the population.

In recent weeks a militantly worded 31-point petition demanding an end to the state’s strict control of the church has been signed by at least 75,000 people. The petition has won the unprecedented endorsement of Cardinal Frantisek Tomasek, the 88-year-old Czechoslovak primate and archbishop of Prague, a step that some church figures suggest is a sign of stiffened will on the part of the church.

Tomasek’s endorsement, read at church services, said there is nothing illegal or unconstitutional about the petition and added that “cowardice and fear are undignified to true Christians.”

In addition to what some describe as a renewal of interest by Catholics, Protestant churches are also experiencing a steady increase in enrollment. Pentecostal and charismatic churches, religious figures say, are attracting new followers in large numbers.

Government Nervousness

Observers of both the political and religious scene say it may be a growing nervousness on the part of the government that has led to a renewal of talks between the state and the Vatican delegation, which is headed by Archbishop Francesco Colasuonno, the special papal envoy for Vatican relations with East European countries.

The talks this week mark the third round of discussions between Vatican officials and the state in the last three months. They began in November, after the funeral of Bishop Julius Gabris, when Archbishop Achille Silvestrini, the Pope’s “foreign minister,” met with the Czechoslovak deputy foreign minister, Jaromir Johanes. It was the first high-level meeting between the two sides in more than two years.

A second round of meetings, with Colasuonno leading the Vatican delegation, was held in December. Spokesmen for both sides have remained tight-lipped about the negotiations.

Although the central point in the negotiations is believed to be the appointment of bishops or auxiliary bishops to the vacant posts, a whole range of issues, especially religious education and the declining number of priests in the country, may be on the table as well.

Some activist priests say they regard this period as especially crucial. They say they are concerned that a compromise by the church on several of its demands could lead to another long period of state domination in return for the appointment of a few bishops, perhaps as few as three.

‘Underground Church’

On the other hand, the growing militancy of the “underground church,” as some human rights activists call it, may suggest to the Czechoslovak government that some strengthening of the traditional church hierarchy may be preferable to a sub rosa church that could turn out to be far more difficult to control and monitor.

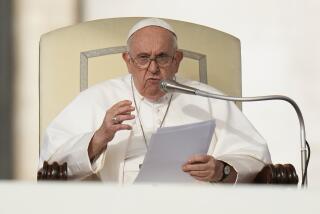

Observers here believe that Cardinal Tomasek, who was jailed in the 1950s and has been regarded generally as a cautious church leader, may have been given encouragement for a tougher stand by Pope John Paul II, who as a former Archbishop of Krakow in Poland is familiar with the struggle of the church in Soviet Bloc countries.

When four Czechoslovak bishops and a layman were denied permission to attend a synod of bishops at the Vatican in October, the Pope said it was a commentary on the “sad state” of the church in Czechoslovakia. The absence of the churchmen, the Pope said, “offers an eloquent indication of the conditions in which the church exists in your regions.”

The director of the State Secretariat for Church Affairs, Vladimir Janku, denied the accusation. He said the bishops did not attend the synod because they were ill.

Another sore point between the church and the state involves the group called Pacem in Terris, an organization of clerics formed by the state to encourage government support from within the church. After a 1982 Vatican declaration against political activities by priests, Cardinal Tomasek pointedly asked the Vatican if the ban applied to Pacem in Terris. The Vatican’s answer was yes.

Dwindling Membership

At one time about a third of Czechoslovakia’s 3,400 priests were enrolled in the organization. Active members now are believed to have dwindled to about 500.

While Pacem in Terris has faded, the activities of the underground church have spread. Samizdat (underground) publications on religion have appeared with more frequency. Banned priests conduct services in private homes. Religion classes for children are secretly organized, combatting what church activists say is discrimination against parents who press school authorities for religious instruction in schools.

Vaclav Maly, a banned, or unlicensed, priest and a signer of the Charter 77 human rights manifesto, believes that the revival of religious interest in Czechoslovakia has clear roots.

“The state,” Maly said, “is in a difficult position. It must officially recognize the existence of the church and yet control it as tightly as possible. There is a paradox here, because as the church becomes more attractive, especially to young people, the more the state opposes it. But this is a small part of it.

“Our society preaches that it has built a society where no one is alone, no one is left behind, no one is left out. But the reverse is true. Society is atomized and so oriented to its private life and private needs that there is no sense of community consciousness or common will. Isolation is the rule, and young people are looking instead for a community, a community without hypocrisy and with values, and this is what brings them to the churches.”

Seek Sense of Belonging

Several other priests and two Protestant ministers, who asked to remain anonymous, agreed with Maly’s assessment.

“People are looking for a sense of spiritual belonging,” one of the Protestants said, adding that membership at his church had tripled in 18 months. “It is a natural impulse,” he went on, “a hunger to search for meaning, and there is no sense of meaning in the propaganda of the state.”

The state, meanwhile, maintains that there is “complete freedom of religion in Czechoslovakia.” Dusan Rovensky, the spokesman for the Foreign Ministry, said:

“Regarding the Vatican, we have an interest in the Vatican not interfering with our internal matters and respecting the fact that there is no separation of church and state in Czechoslovakia. We cannot accept the fact that the Vatican does not agree with our views concerning who is assigned to certain positions.’

Rovensky said the Czechoslovak government would like to see its relations with the Vatican as “part of a broader international dialogue; we will not accept a dialogue that infringes on our internal affairs.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.