Takes Up Plight of Infected Bar Girls Who Cater to U.S. Forces : Philippine Mayor in Front Lines of AIDS War

- Share via

OLONGAPO, Philippines — The 18-year-old bar girl said she wanted to kill herself, so Richard Gordon, the mayor of this city outside the U.S. naval base, produced his 9-millimeter automatic, placed it in front of her and said, “OK, go ahead.”

The girl, one of 26 AIDS victims in Olongapo, studied the gun for a moment and then broke down. She and the mayor ended the session in a tearful embrace. But Gordon knew he had not gotten through to her.

That was 30 days ago. Finally, on Tuesday morning, Gordon reached her.

Tough Veneer Melts Away

After another hour of emotional dialogue with the 18-year-old and a dozen other AIDS-infected “hospitality girls,” the tough veneer she had built up during four years in the go-go bars outside the giant Subic Bay Naval Base seemed to melt away.

She realized she was going to die. She realized she could kill. And she agreed to quit the bars and work in the mayor’s City Health Center.

So did eight of the other young women, all of whom had been working in the bars that cater to U.S. sailors and Marines even though Navy doctors had examined them and found they tested positive for the HIV virus associated with acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

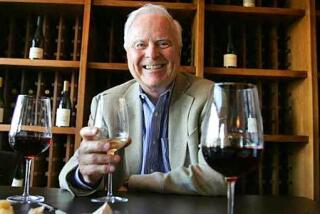

Gordon, 42, is trying to stem a budding AIDS epidemic in this city, which has 6,000 prostitutes and a red-light district of 285 clubs that cater to thousands of American personnel.

The mayor has pledged to meet every month with the 26 AIDS victims, identified by means of an intensive, Navy-financed screening program at clubs and massage parlors throughout the country.

Dual Problem for Navy

At Olongapo and at Angeles City, site of Clark Air Base, the infected women pose a dual problem for the U.S. government. There will be negotiations this year on extending the agreement on the bases, and sure to come up are allegations by Filipino nationalists and leftists that the bases are responsible for introducing AIDS into the Philippines.

In the short term, the men of every U.S. Navy ship that visits the base at Subic Bay--the aircraft carrier Midway is in this week, together with its support ships--is exposed to known AIDS victims working in Olongapo’s bars.

For the city of Olongapo, AIDS poses the problem of caring for dozens of patients--and the city is broke.

On the first Tuesday of every month, Gordon sees as many of the infected girls as will come to the health center, where, under city law, about 500 young women are tested every day for AIDS and venereal diseases. Gordon listens to what they have to say, he preaches a bit, he cries with them. More important, he tries to get them out of the bars and into jobs that will make it possible for health workers to keep track of them.

On this Tuesday, the nine young women accept Gordon’s offer of clerical work at the clinic. They will be paid 700 pesos a month--about $35--a tenth of what they make in the bars when there are ships in port.

“Yes, money is important,” he told the women Tuesday, as many of them shook their heads over the prospect of such low pay. “But you can’t buy self-respect. Once you lose your dignity, you have lost everything. The only way you’re going to solve your problems is by helping others with theirs.”

“You know, I blame poverty for all of this,” Gordon said to a reporter afterward. “It’s not the U.S. bases. It’s the inability of our national government to solve the basic poverty of our people. So the object of this exercise is to get these girls off the street and to restore their dignity.”

Tough Stance With Navy

Nonetheless, Gordon is getting tough with the Navy, too. At a meeting of a recently formed AIDS committee that includes Navy representative and local residents, he told two Navy public health workers, “It’s time to shake the tree, gents, and I’m shaking it.”

He told the Americans that he needs money to pay the young women in their new jobs and a van and surplus Navy trailers to house all the unlicensed and untested streetwalkers who invade the red-light district when ships come in. He said he also needs the help of naval intelligence in identifying the source of illicit drugs used by the bar girls.

“Lieutenant,” Gordon asked the chief public health officer at the base, “how long are you going to be stationed here?

“I leave in August, mayor,” the officer answered.

“Lieutenant,” Gordon went on, “you will leave, but the problem will stay here. Soon these girls are going to start getting sick. They’ll need medical care. Gentlemen, we’ve got a helluva problem, and I’m asking for your help.”

Asks for Trust

The Americans promised to do what they could.

In his sessions with the young women, Gordon asks for even more. He asks for their trust, for he is trying to establish personal relationships that will allow health workers to keep track of them. They cannot, under the law, be quarantined.

The 18-year-old was the most difficult. At Gordon’s first session, a month ago, he had challenged her. He said that most of the infected girls “have an almost childlike naivete about what is going to happen to them, because they don’t feel sick yet.” But the 18-year-old knew she was going to die.

When he handed her his pistol, he said, she cried, but only because she lacked the courage to use it.

Not until a week ago, the teen-ager told Gordon on Tuesday, did she begin to trust him. She had overheard him talking on the radio about the city’s AIDS problem, about an anonymous young woman and his gun. During the broadcast, he wept.

“I heard that, mayor,” she told him Tuesday. “I heard you cry for me.”

Pour Out Stories

As she spoke, many of the other young women at the clinic wept, too. And along with their tears, they poured out their stories.

One told of returning to her home province in January to deliver a baby, and of her doctor placing a sign over her hospital bed that read, “This Girl Has AIDS.”

Another said that after her neighbors learned she had AIDS, they told her to hang herself. When she refused, she said, they told her to move away.

“Why don’t you girls get a house or an apartment and share it, help each other?” the mayor suggested.

“Hey, good idea,” several agreed.

When the session ended, Gordon--obviously drained by the experience--said:

“It’s a start. But, you know, I keep looking for someone to blame, and I realize everybody is partly to blame. I just wish everyone would try to solve it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.