Research Promising : Use of Fetal Tissue Stirs Hot Debate

- Share via

When diabetic Rich Shultz received a transplant of pancreatic cells taken from an aborted human fetus two years ago, the Santa Barbara man became a participant in a fast-growing but controversial field of experimental therapy.

Many biomedical researchers believe that fetal tissues and cells have enormous potential for helping hundreds of thousands of people with hormone-deficiency disorders such as Parkinson’s, Huntington’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, as well as diabetes. But these experiments are raising a host of ethical, medical and legal concerns, including the fear that this technique might prompt women to become pregnant simply to generate fetuses whose cells and tissues could be sold.

Government Acts

Such questions prompted the Reagan Administration to ban all human experiments at the National Institutes of Health that use tissue from aborted fetuses. In announcing the action, Dr. Robert E. Windom, assistant secretary of health at the Department of Health and Human Services, also directed the NIH to form “one or more” outside advisory committees to “examine comprehensively” the far-reaching implications of this fast-growing field.

Windom’s decision, revealed on Thursday, came in response to a proposal from an NIH researcher to implant fetal brain tissue into a patient with Parkinson’s disease.

In an interview Friday, Windom said the ban will not affect similar research by university scientists, who have done the bulk of the pioneering work in the field.

Still, the ban is raising concern among academic scientists who fear that it may have a spillover effect. “The restrictions will hurt all biomedical research. The NIH is supposed to be the research leader. This is a precedent that is very difficult to accept,” said Dr. Bernard Leibel, a University of Toronto diabetes expert.

Shultz, a 28-year-old researcher for a defense contractor, is among about 150 people who in recent years have received fetal cells to experimentally treat diseases brought on by the death of hormone-secreting cells. Scientists believe that transplants of adult or fetal cells that secrete the same hormones might reverse the course of such diseases.

Scientists are concentrating, for the most part, on fetal rather than adult cells because fetal cells are less likely to be rejected after implantation.

But fetal cells are in very short supply. Many researchers now are looking for ways to induce such cells to proliferate in the laboratory, which has for the most part proven to be an an elusive goal. So far, only one commercial firm has reported that it has found the formula to do so, but it is keeping it confidential.

Until the supply problem can be overcome, researchers have established little-known arrangements with some abortion clinics and hospitals to supply fetuses, an expanding network that few are willing to talk about for fear of losing their sources.

Fetal cell transplants “represent very significant therapeutic possibilities for many people,” said bioethicist Mary Mahowald of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. “But there are very complicated and controversial questions that come with it, so we need to proceed with as much care as possible.”

Since the 19th Century, scientists have been dissecting fetuses obtained at different stages of gestation to study the complex, mysterious mechanism by which a fertilized egg develops into a human being. But it has only been since the 1940s that researchers have studied the biochemical mechanisms by which fetal tissues function as a way to find new treatments for diseases.

More recently, such research has accelerated with the apparent success in treating Parkinson’s disease and diabetes with the use of transplanted cells.

Today, such research represents only a fraction of U.S. biomedical research.

In 1987, about 118 U.S. research groups received $11.8 million--about 2% of NIH’s total budget--for research involving fetal cells, according to Charles R. McCarthy, director of the NIH Office of Protection From Research Risks.

Most researchers use fetal cells to obtain clues about how various types of cells function.

At Ohio State University, for example, radiologist Altaf A. Wani is looking for new ways to prevent cancer. He does so by growing fetal skin and nerve cells in the laboratory and exposing them to cancer-causing chemicals or radiation. How those cells might repair themselves could lead to new cancer drugs. Adult tissues cannot be used, he said, because they do not grow as well in the laboratory.

Studies Cells

At the University of Texas in Dallas, endocrinologist Bruce Carr is studying heart disease and looking for new drugs to reduce cholesterol. In the laboratory, he exposes fetal liver tissues to hormones and other drugs, and then studies how the chemicals alter the cells’ ability to produce cholesterol.

“Such studies are a critical factor in research in virtually every major disease category,” McCarthy noted in an interview before the NIH ban was announced.

Only a “handful” of researchers are studying the potential use of fetal cells in human therapy, primarily for diabetes and Parkinson’s, he added.

Three U.S. research groups have implanted fetal pancreatic cells in 48 diabetics, and one of the teams, Alameda-based Hana Biologics Inc., plans to implant laboratory-grown fetal pancreatic cells in another 120 diabetics in the fall. As many as 100 diabetics in China have also been treated with fetal pancreas cells, according to endocrinologist John A. Colwell, president of the American Diabetes Assn. The Chinese have not yet announced their results.

McCarthy and other experts predict that U.S. researchers will soon begin using fetal brain cells as an experimental therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Within the last year, more than 100 U.S. Parkinson’s victims have had at least some of their characteristic tremors and limb rigidity alleviated after surgeons grafted part of their own adrenal glands into the brain, where the adrenal tissues secrete a hormone crucial to brain functioning.

But experiments on animals suggest that fetal brain cells may be much more effective than adrenal cells in reversing Parkinson’s. Surgeons in Mexico, Cuba and Sweden have in the last four months implanted such cells in five victims of Parkinson’s, although no results have been reported yet.

(There are no federal regulations governing such human experiments, but academic researchers must obtain approval from their own institutions before embarking on the experiments. And it is not inconceivable that such institutional review boards now would take into account the NIH ban.)

If the diabetes and Parkinson’s trials are promising, experts said, the bulk of the 1.5 million Parkinson’s victims and the 500,000 insulin-dependent diabetics in the United States might become candidates for fetal cell therapy.

For now, most researchers believe that diabetes may be the disease most amenable to experimental therapy with the use of fetal cells because it is caused by the death of only one type of cell--and a highly specialized one at that.

The disease is the third leading cause of death in the United States, after heart disease and cancer. It typically develops before the age of 20, triggered by the death of insulin-secreting cells, leaving other cells in the body unable to assimilate sugars. When body cells use fats for energy instead of sugars, they produce toxic chemicals that can cause coma and death.

Injected insulin allows the body to use sugars and prevents immediate death. But wide swings in blood sugar concentrations occur between insulin injections. Many physicians believe that these swings are responsible for the long-term complications of diabetes.

Immune Response

Such complications might be avoided if insulin was released into the blood only when needed, according to immunologist Bent Formby of the Sansum Medical Research Foundation in Santa Barbara. A pancreas transplant might achieve this goal, but transplanted pancreases normally provoke a strong immune response, making this organ even more likely to be rejected than a heart or kidney.

Moreover, only small clusters of pancreatic cells, called islets, actually secrete insulin. The rest of the pancreas, which is about the size and shape of a fillet of sole, produces only digestive enzymes and plays no role in diabetes.

It is very difficult to separate adult islets from the pancreas for transplants, Formby said. But islets develop earlier than the enzyme-producing cells and, at about the 14th week of gestation, can be separated readily from the aspirin-sized fetal pancreas.

Shultz was one of seven diabetics who have had such islets implanted at Sansum, a small diabetes research institute founded in 1944 by Dr. William D. Sansum, who was the first American to use insulin to treat diabetes.

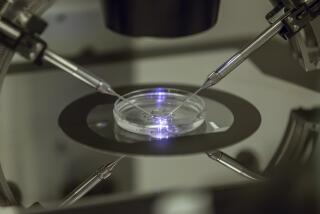

To perform an implant, Sansum technicians slice fetal pancreases into small pieces and treat the pieces with enzymes to free the islets. About 25 fetal pancreases would be necessary to provide sufficient daily insulin for an adult--for as long as the cells live. But Formby said he has never been able to obtain more than 14 in his weekly shipments.

The ability to keep such cells alive varies greatly among laboratories, ranging from days to months, according to researchers in the field.

In the actual transplants, Sansum physicians implant the islet cells between the skin and muscle of the patient’s lower abdomen in a 30-minute operation performed under a local anesthetic. Once in place, the cells immediately begin to secrete insulin in response to increased concentrations of sugar in the blood stream.

What happened to Schultz was typical of the experience at Sansum, where five principal researchers have a yearly budget of $4.5 million provided by private donors and diabetes foundations.

Within a week after his operation, the fetal cells were producing enough insulin to allow Schultz to reduce his daily insulin dosage by half.

But in the course of the first year, his insulin requirements gradually rose because about half of the implanted cells died--probably because they were rejected, Formby said.

However, the surviving cells are continuing to produce about 20% of Shultz’s daily insulin requirement--enough to smooth out the sharp swings in blood sugar levels and make his disease more manageable.

Before the operation, he said, a milkshake or chocolate bar would cause his blood sugar to rise sharply, making him lethargic. Now, the effects of such sweets are much less severe, he said.

The first scientist to transplant fetal islet cells in humans was immunologist Kevin Lafferty of the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver, in 1985.

Lafferty refused a request for an interview, but Bobbie Barrow, a university spokeswoman, said in a prepared statement that Lafferty has transplanted cultured cells in 17 insulin-dependent diabetics who had already received kidney transplants because high sugar levels had damaged small blood vessels in their own kidneys. Such patients were already receiving drugs to suppress rejection of the kidney, and were thus less likely to reject the pancreas cells.

Five of seven patients given “large amounts” of the cells required fewer insulin injections after the surgery, Barrow said, some for as long as 1 1/2 years. The treatment provided no benefit for patients who received fewer cells, she added.

The third U.S. group involved in experimental fetal cell transplant is Hana, which has spent the last five years developing ways to grow fetal pancreas cells in the laboratory, according to Craig McMullen, Hana’s president.

Using specially developed nutrients and growth enhancers, he said, the company is now able to grow enough cells from one fetal pancreas to treat 20 adult diabetics.

Much More Efficient

With this technique, instead of needing 25 fetal pancreases to treat one adult, Hana can obtain enough islets from one fetal pancreas to treat 20 patients--making its technique 500 times more efficient than Formby’s.

To test the safety of those cells--a standard medical practice--surgeons at four medical centers have, since last August, implanted the fetal cells in 24 diabetics, McMullen said. By this September, Hana hopes to expand the trials to 120 patients at 12 medical centers to test the cells’ efficacy. McMullen would not reveal the names of the centers because, he said, “we are afraid the centers would be swamped by diabetics demanding treatment.”

(Although the implants are not covered by any federal regulations, Hana nevertheless is testing the cells’ safety in case the U.S. Food and Drug Administration ultimately were to classify such cells as a drug.)

Hana hopes to be able to provide cells for 15,000 transplants per year by 1991, McMullen said.

The company has also been developing similar techniques to grow fetal brain cells for the treatment of Parkinson’s and are now testing them in animals. McMullen said it will be at least 18 months before human trials can begin.

Obtained Fetal Tissues

Initially, Sansum, Lafferty and Hana all obtained fetal tissues from the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI), a nonprofit, NIH-funded foundation created in 1980.

The Philadelphia-based interchange serves as a clearinghouse primarily for organs and tissues removed during autopsies and surgeries. Such materials are useful in many types of research, and NDRI has provided 32,000 organs to about 350 researchers throughout the country.

Volunteers at NDRI’s network of Eastern hospitals obtain informed consent from tissue donors or the mothers of fetuses and notify NDRI of an organ’s availability. The agency then notifies researchers who need that tissue, and may help arrange transportation.

But early last year, said Lee Ducat, NDRI president, the foundation’s volunteers became reluctant to collect fetal tissues because of a growing fear of pressure from right-to-life groups.

Ducat could not identify any event that precipitated the change in attitude, but said: “We haven’t collected any fetal tissue at all since last June. . . . It’s very frustrating . . . because we know that the tissue is being . . . thrown away.”

Many researchers who received fetal tissues from NDRI are now obtaining them from the even more obscure International Institute for the Advancement of Medicine, a nonprofit foundation established in 1986 by a former NDRI staff member in Havertown, Pa. The institute differs from NDRI in that it rents space in hospitals and clinics and hires its own technicians to process and forward tissues.

In 1987, the institute supplied about 1,800 tissues to researchers, said director Jim Bardsley. So far this year, it has been processing 500 specimens per month--about 60% of them fetal tissues. The institute is now working with 44 research groups that need fetal tissues, he said.

Bardsley would not divulge the names of participating hospitals and clinics because, he said, “We don’t want to motivate any aggression.”

Like the experimental use of fetal cells, the collection and distribution of the tissues also are not regulated by either the states or the federal government. But activist Jeremy Rifkin of the Foundation on Economic Trends in Washington, has accused both NDRI and Hana of buying and selling fetal tissues, and he has petitioned the Department of Health and Human Services to ban the sale of fetal tissues.