2 Decades Later, ‘Gentleman Traitor’ Talks of Treachery in Controversial Interview

- Share via

LONDON — On four recent Sundays, the ghost of treachery joined Britons at the breakfast table.

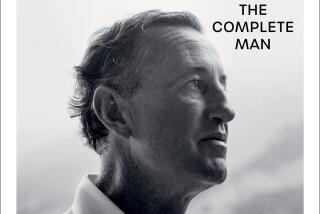

Harold (Kim) Philby, the gentleman traitor who spied for the Soviet Union, granted his first interview to a Western journalist since defecting to Moscow in 1963, and it appeared in the Sunday Times beginning in March.

Critics say publication of the four-part interview in the Times, with a circulation of 1.4 million, was a propaganda gift to the KGB. The Soviet secret police agency still employs Philby, now 76.

For journalist Phillip Knightley the evening of Jan. 19, when he entered Philby’s apartment in Moscow, climaxed 20 years in which he secretly corresponded with Philby but the master spy repeatedly refused to see him.

When he did agree to talk, Philby dropped no bombshells. But the myriad details reveal an English gentleman who despised his privileged background, espoused Soviet communism as a Cambridge University student in the 1930s and penetrated the highest levels of British intelligence in the Kremlin’s service.

Because of his high contacts in Washington, Philby was able to betray the whole Western alliance. He sent many Western agents to their deaths and was even able to head off the defection of a Soviet diplomat who threatened to expose him.

The most controversial point in the interview is Philby’s contention that British intelligence let him defect rather than face an embarrassing public trial.

Philby told Knightley that he suffered severe self-doubt after fleeing to Moscow and began drinking heavily.

“Doubt is a terrible thing,” he said. “Had I done the right thing? You see, I never swallowed everything (about Soviet communism). I never took it all in.”

Philby said he has found peace and a happy fourth marriage, to a Russian woman, feels at home in the Soviet Union and believes today’s England would be a foreign country to him.

“No faith? Come, come,” he said. “Only a fool would deny me my faith.”

He likes to keep in touch with British gossip, listens to the BBC, does the Times of London crossword and misses English mustard.

Ever the gentleman, he greeted Knightley at his door with a cheerful: “Come on through, dear chap.”

“I don’t like deceiving people, especially friends, and contrary to what some people believe I feel very badly about it,” he said in the interview. “But then, decent soldiers feel badly about the necessity of killing in wartime.”

The unmasking--after Philby had been under suspicion for 12 years--climaxed a nightmare episode for British intelligence.

It began in 1951 with the defection of top spies Guy Burgess and Donald McLean and reverberated into the 1980s with the revelation that Anthony Blunt, another upper-class Englishman, had been unmasked as a traitor secretly and went unpunished.

When Philby defected, Blunt was given immunity from prosecution in exchange for information. He later became art adviser to Queen Elizabeth II.

Blunt died in 1983, but the scandal continues to shake the intelligence establishment. There are allegations that the late Sir Roger Hollis, director of the MI5 intelligence service from 1956 to 1965, also worked for the KGB.

Some commentators feel things have gone too far.

“These treacheries marked the end of a certain idea which the British upper classes once entertained of themselves. But all that is over now. Its legacy, unfortunately, is increased cynicism and incipient paranoia,” Anthony Hartley wrote in The Sunday Telegraph.

Others ridiculed Philby’s notion that he was allowed to defect.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.