Strategic Arms Reduction Talks

- Share via

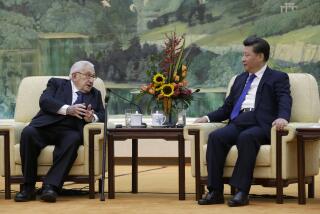

Henry Kissinger concludes his analysis of the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks, or START, by stating, “START should not proceed further until the American people and our allies have been told where this process is leading” (Opinion, April 24). I agree, because the fact is that most people are totally unaware of what START really means in terms of arms control and strategic stability.

As presently configured, START will only eliminate 30-35% of existing strategic forces, rather than the 50% figure claimed by the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The reason for this discrepancy has to do with the way in which weapons carried on bombers are counted. Far more important, however, is the fact that START is not a freeze; it will do nothing to halt most of the U.S. and Soviet weapons modernization programs currently under way.

Under the SALT II Treaty (which the U.S. ceased to comply with in 1986) both sides were permitted to develop only one new type of ICBM. This, coupled with a ceiling on total numbers of launchers, placed some limits on force modernization. START provides no such restrictions. This raises the possibility that Kissinger finds so ominous--that U.S. (and Soviet) forces will be more vulnerable after the implementation of a START agreement than they are at present because older, less accurate weapons will be replaced with newer, more accurate weapons.

The SALT I Interim Agreement of 1972 essentially froze at existing levels the number of U.S. and Soviet ballistic missiles. At that time the U.S. was developing and deploying MIRVs--multiple independently targeted reentry vehicles--to penetrate a Soviet ABM system and to provide increased target coverage. The Nixon Administration, with Kissinger as national security adviser, refused to negotiate a ban on MIRVs hoping instead to use the technology to remain superior to the Soviets.

Predictably, MIRVs decreased stability because once the Soviets mastered the technology they were able to threaten the destruction of U.S. land-based forces with a first strike, eventually opening up the infamous “window of vulnerability.” Today, with large numbers of MIRVs, both sides can for the first time seriously consider fighting a nuclear war.

For all these reasons, Kissinger stated only a few years ago that not seeking a ban on MIRVs was the biggest mistake he ever made. Unfortunately, he seems not to have learned anything from this mistake.

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ

Associate Director

Council on Nuclear Affairs

Santa Monica

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.