May Help Free 3 Hostages : British Mission Seeks to Thaw Iran Relations

- Share via

LONDON — Four members of Britain’s Parliament depart for Tehran today on a mission they hope may eventually lead to the release of three British hostages held captive in Beirut.

The mission, sponsored by the Church of England, aims to improve long-frigid relations between Britain and Iran, a move that the members of Parliament argue is essential to win the captives’ freedom. The church’s special envoy, Terry Waite, is among the hostages.

“It is a fact-finding mission to find ways to improve relations with Iran which could lead to the freeing of . . . Waite and the other British hostages,” said Eve Keatley, an assistant to Archbishop of Canterbury Robert A. K. Runcie.

Mood of Frustration

The trip unfolds amid a public mood of frustration with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s policy of refusing to initiate diplomatic action to free the British hostages. While the Foreign Office has made no attempt to block today’s trip, it clearly does not support it.

“This is not our show; our view to this is agnostic,” a Foreign Office spokesman said. “Everyone is well aware (that) the British government policy is no deals.”

Thatcher has consistently proclaimed her refusal to negotiate for the release of the British hostages, arguing that such a move would only reward the captors and encourage more hostage-taking.

The United States, West Germany and France have all successfully bargained for the release of at least some of their citizen hostages in recent years.

The British delegation includes two members of Thatcher’s Conservative Party and a Labor Party member, all from the House of Commons, and Lord Geoffrey Tordoff, a Social and Liberal Democrat from the House of Lords.

“Our principal objective is hopefully to contribute in some small but positive way to an improvement in the political climate and the relationship between Iran and the United Kingdom,” said Robert Hicks, a Tory member of Commons.

Public Sentiment Grows

Public sentiment to take action grew last month with the release of the three remaining French hostages after a controversial deal that included re-establishment of diplomatic relations between France and Iran.

The visibly poor physical and emotional state of the freed Frenchmen and their descriptions of the terrible conditions of their imprisonment also stimulated a sense of urgency to free the three Britons.

In recent months, friends of British hostage John McCarthy, a television journalist, have abandoned the low profile urged by the government and conducted a highly visible campaign to put pressure on the government to negotiate for his release.

Ex-Hostage Demonstrates

Last week, a recently freed French hostage, Jean-Paul Kaufmann, joined a group of McCarthy’s friends on a publicized boat trip along the Thames River near Parliament to draw attention to his plight.

McCarthy, now 31, was kidnaped two years ago as he drove to Beirut airport. Waite, 48, was taken prisoner in January, 1987, as he attempted to negotiate the release of the remaining American hostages. The third British hostage, 38-year-old university lecturer Brian Keenan, was kidnaped in April, 1986. Keenan also holds an Irish passport.

The three Britons are among 18 foreign hostages believed to be held by Muslim radicals with strong ties to Iran. Nine of the 18 are Americans.

State Department officials in Washington have denied reports that the United States recently made contact with Iran through diplomatic channels in Geneva in search of new ways to gain the release of the American hostages.

One of the Britons traveling to Tehran said that the mission was initiated by a personal invitation from Hashemi Rafsanjani, the influential Speaker of Iran’s Parliament, but the official Iranian news agency denied this Saturday, saying that Iran’s Foreign Ministry had simply responded to the Church of England’s request for the visit.

While the four members of Parliament received Foreign Office briefings last week, a Foreign Office spokesman stressed that this was a routine courtesy provided any member of Parliament traveling overseas.

“Our relations with Iran are at a fairly low ebb, but the ball is in the Iranian court,” the spokesman said. “They have to show that they can conduct their relations like a normal country.”

The main British diplomatic effort to secure the hostages’ release has been in Beirut, where members of the small British mission occasionally venture into West Beirut to follow up specific leads.

Anglo-Iranian ties deteriorated quickly after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, and last year a series of diplomatic expulsions and the beating of a British envoy in Tehran left the countries with only one representative in each other’s capital.

Earlier this month, however, the two countries conducted their first official-level talks in nearly two years, arriving at a formula for compensation of damages to the embassies of both countries.

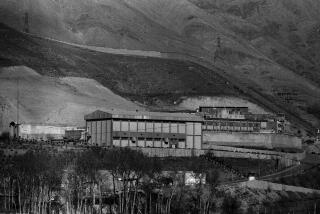

The British Embassy in Tehran was damaged during the political turmoil surrounding the revolution, while Iran’s Embassy in London was gutted in 1980 when British army troops stormed it to free hostages taken there by anti-Iranian terrorists.

Iran also recently issued a visa to the brother of a British national jailed in Tehran for the past two years.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.