Last Echo of a Voice Gone Still

- Share via

With all the other things and services they offer, newspapers and magazines provide voices, individuals identifiable by name and attitude.

Starting his news magazines, Henry Luce thought otherwise, and established in our century the idea of group journalism, with a collective, unsigned voice that was unique, corporate and, above all, authoritative. The joke was that Time-style was the way God would write if He had all the facts.

It served Luce well for years, although Time’s sister publication, Life, always had a few signed pieces amid the generally anonymous text. But Time gradually added signatures to many of its stories, identifying writers, reporters and critics. Now I see that it has gone to bylines. (“Inevitable, if we’re to be competitive,” the editor of Time, Henry Muller, remarked at a cocktail party a few days ago.)

The then-editor of Life had the same perception some years ago and assigned one of his staff writers to do a personal column called “The View From Here.” The viewer was a tall, gentle, rumpled man named Loudon Wainwright, and he wrote the column for 24 years until he died on Monday from cancer at the age of 63.

The column was always a pleasing paradox, a self-revealing and even confessional voice, thoughtful, concerned and unpretentious, amid the collective grandeurs of photo-journalism.

Loudon had come to the magazine in 1949, taking over the trainee job I’d held for six impatient months in the magazine’s picture bureau. (The official obituary said he’d begun as an office boy and I suppose that’s what we were, but we thought of ourselves as trainees, bound for whatever glories we could devise.)

He was from the start a figure of awe among us, because had already had a short story published in the New Yorker. It was called “The Gentle Bounce,” and was drawn from his days at the University of North Carolina.

Later we both wrote news stories for the magazine, he in sports, I in politics and other disasters. We endured the late-hour closings on airless, sticky summer Saturday nights in the old, non-air-conditioned Time-Life Building in Rockefeller Center.

One night, unable to get a headline the editor liked (they were 17 1/2 typewriter characters wide and miserable to concoct), Loudon printed and tacked above his typewriter a little sign that said, “How Can He Be So Sure What He Wants and Not Know What It Is?”

He was, more than most of us, a free spirit who occasionally wandered off from cocktail parties and, answering some primal instinct, got on a train and rode back to his old prep school, as if for renewal and reassurance.

He played guitar and wrote songs, one a melancholy anthem called “Man Is Just a Handful of Dust,” which he did for us on request, often. Those talents passed to his son, Loudon Wainwright III, who has achieved some fame as a folk singer and of whom his father was proud and, I suspect, more than a little envious.

Loudon worked as the Life bureau chief in Southern California for a time and was said to have been arrested one larky night for tossing lighted firecrackers from a car. The Beverly Hills police have a limited sense of fun.

In the columns he was frank about his foolishnesses. Writing about Billy Martin, he admitted a kinship because he had been found “equally unacceptable by the owners of occasional saloons.”

The success and strength of “The View From Here” is that Loudon took the reader so effortlessly from the private particulars to a more general truth. The gift of finding the sublime in the ridiculous was one he shared, I think, with E. B. White.

He found Billy Martin’s later antics unattractive and saw in them Martin’s sad refusal to accept the passing of his own myth as a boy-hero. Loudon understood, if Martin didn’t, that for all baseball’s timeless qualities, things never stay the same.

Ross Macdonald once wrote about writers dropping personal clues, like burglars who want to be caught: “our fingerprints on the broken locks . . . our footprints in the wet concrete and the blowing sand.”

Loudon left his own clues, particularly in the last months he was writing. The reference to his troubles with saloons was followed a few issues later by a reference to an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting that seemed clearly the view from within.

Still later, musing on the awful, televised confessions extracted by Phil Donahue and other hosts, he quoted a reaction to the phenomenon from his oncologist, on whom he had dropped in, he said offhandedly, for some chemotherapy--the first clue for his readers, I believe, that he was ill.

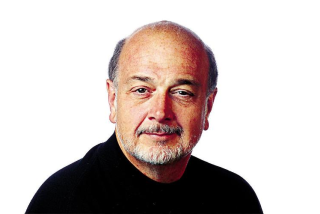

Over the years he had come to look less like an amiable ex-jock than an Old Testament prophet, with a great mane of hair and a full grizzled beard.

In addition to his columns, he had written his magnum opus, “The Great American Magazine,” a history of Life that combined massive research and personal experience, graceful writing and a sharp candor that acknowledged both the bright and dark sides of life at Life. It had taken him a decade and represented among other things a triumph over a writer’s block of skyscraper size.

The last column to appear, in Life’s current issue, is a celebration of his lifelong love of maps, maps for their own sake and as a metaphor for his love of travel and exploration.

“Maps, of course, are just excuses for the journeys they set us on,” Loudon wrote. He talked lovingly of following fog-shrouded lanes down to the Maine shores and pursuing back roads in Upstate New York and on the mesas of New Mexico between Sante Fe and Taos.

He was already planning his next column, he told me on the phone a couple of weeks ago. But in the piece about maps he had given his steady readers an obliquely stated clue that it might not be.

“Much as I’d like to plan for some good coastal trips, I’m not really up for them,” Loudon wrote. “The possibility of other trips--more engulfing--intrudes, and I am unsettled by possible destinations. As much as I think I’m ready for anything. . . . I’m not ready to see where all roads come to an end.”

The final view from where he was, like everything else he wrote, was honest, eloquent, civilized and very affecting, and I mourn that the roads have ended and the voice gone still.