Honduras in Turmoil : The Puzzling Life, Death of Gen. Alvarez

- Share via

TEGUCIGALPA, Honduras — The day he died, Gustavo Alvarez Martinez awoke before dawn, entered his study and opened a Bible. Spreading his hands over a map of Honduras, he prayed for his people: “Blessed is the nation whose God is Jehovah.”

As military commander in chief from 1982 to 1984, Gen. Alvarez was a powerful U.S. ally who battled communism by force of arms. He waged a fierce counterinsurgency campaign at home, helped launch the war by U.S.-backed Contras against Nicaragua’s Sandinista government and plotted to seize part of Nicaragua.

Notorious, Visionary

But after being ousted by fellow officers, Alvarez found Christ, gave up his pistol and repented. Rejecting bodyguards, he returned after four years in exile to tour Honduras on an equally zealous mission: to convert the souls of his countrymen and make them God’s “chosen people.”

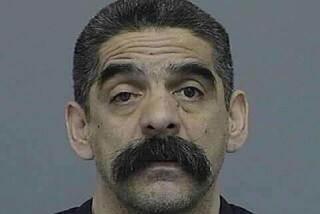

On Jan. 25 after breakfast, the 51-year-old Alvarez left his neocolonial home to pick up a Hebrew-Spanish Bible, a gift from the Israeli consul. Along the way, seven men wearing the white hard hats and blue uniforms of the Honduran telephone company ambushed his Toyota pickup with Uzi submachine guns, killing one of the most notorious and visionary figures of Central America’s bloody history.

To many Hondurans, the general’s controversial life and unsolved murder symbolize this poor, sleepy country’s precipitous slide into violence. Coming amid a surge of killings, bombings and death threats, the assassination has heightened the sense of insecurity in Honduras over the consequences of the Contras’ apparent defeat.

“Alvarez took refuge in religion, perhaps to justify himself, perhaps to save the country from the violence he helped inaugurate,” said Manuel Acosta Bonilla, a respected lawyer, politician and critic of the armed forces. “But he became a victim. He reaped what he sowed.”

Labyrinth of Forces

Who killed Gustavo Alvarez Martinez is a mystery that leads into a labyrinth of forces that entwine in Honduras. Without a war of its own, the country has played host since the early 1980s to an uneasy mix of Contras, Sandinista spies, U.S. troops, Salvadoran refugees, CIA agents and cocaine smugglers.

Hours after his death, news media received a typewritten message allegedly from the Cinchoneros, a home-grown leftist band thought to have been wiped out by Alvarez’s forces. The message said a Cinchonero squad executed “this psychopathic general” for waging “dirty war” in Honduras and trying “to mock popular justice by masquerading as a gentle and repentant Christian.”

Police and army investigators give credence to this claim, without any arrests or additional evidence to back it. But many Hondurans, including some in the Alvarez family, say the general had powerful enemies in the military and might have been killed to keep him from staining them with his public confessions.

There is also speculation that the case is somehow tied to the earlier gang-style killings of Manuel Adan Rugama, a Contra commander, and Carlos Diaz Lorenzana, the Honduran lawyer of accused narcotics kingpin Ramon Matta Ballesteros. All three murders were committed with Uzis on the streets of this capital over a 19-day period.

Death Threats, Bombs

Since then, the Anti-Communist Action Alliance, a secret group, has issued death threats against five leftist political leaders. Bombs have hit Tegucigalpa City Hall, the Interior Ministry, the Standard Fruit Co., Peace Corps headquarters and a bus carrying U.S. soldiers, wounding 15 people.

Political violence on this scale has not visited Honduras since the early 1980s, when Alvarez took command of the military and launched two crusades: an open one against leftists at home and a secret one against Nicaragua’s Marxist-oriented government.

Alvarez was the only one of nine siblings to follow his father into the army. A rebellious child, he once sawed the legs off a table at home to turn it into a “tank” for war games. Defying his father’s wishes, he went to Argentina and entered the military academy, borrowing money from an older brother.

A student of military history, he so admired Erwin Rommel, the World War II commander of German forces in North Africa, that he named one of his own sons Erwin and another Manfred, after Rommel’s son. But Alvarez’s guiding anti-communist creed was more a product of infantry training at Ft. Benning, Ga., in the late 1960s, according to his brothers.

Critics charge that Alvarez also brought home the death-squad methods used by his Argentine mentors against leftists in their country in the 1970s. According to human rights groups, at least 120 leftists seized by Alvarez’s security forces disappeared in Honduras.

In the anti-Sandinista campaign, Alvarez was out in front of the Reagan Administration, giving sanctuary and ferrying arms to the rebels before the CIA took charge. “Everything you do to destroy a Marxist regime is moral,” he once was quoted as saying.

After accepting a growing presence of U.S. troops here, he tried to press on Washington a scheme to have the Contras seize a “liberated zone” in Nicaragua and thus provoke a military confrontation between the Sandinistas and the United States.

“To the extent that any one person had provided a guiding vision and strategy for the Contras, Alvarez had been it,” Roy Gutman, a historian of the conflict, wrote in his book “Banana Diplomacy.”

Alvarez’s downfall occurred after Washington balked at his scheme, prompting fellow officers to question his all-out support for the Contras as too risky. In an army traditionally run by high-level consensus, his Prussian style did not help. At a meeting of the high command, he threatened to remove several officers for “inefficient” performance, and he tried to change promotion rules without consulting his colleagues.

In March, 1984, Alvarez was arrested, handcuffed and flown out of Honduras. He was accused of corruption--pocketing other officers’ Christmas bonuses and taking kickbacks from a company that sold cars to the army--but the charges were eventually dropped.

‘Sin of Pride’

Alvarez later called that moment the start of his religious conversion. “They treated me like the worst delinquent,” he said. “I was tremendously humiliated. Because I had committed the sin of pride, the Lord made me bite the dust.”

During his exile in Miami and after his return to Honduras last spring, Alvarez gave several interviews to Honduran news media and scores of testimonials to religious congregations, some of which were taped.

Those accounts, and interviews with his widow, two of his brothers and two of his children, portray a dramatically changed man who quickly put his military career behind him to become an evangelical missionary.

Never again did he wear a uniform or a side arm. He forgave his enemies and, years later, embraced the officer who had held him at gunpoint during his arrest.

He publicly confessed marital infidelity and became a model family man, converting his wife and five children with him from Roman Catholicism to an interdenominational Protestant creed. He sold one home and took out mortgages on the two others to devote himself to full-time preaching.

“He traded Rommel for Jesus Christ,” said Gustavo Alvarez Jr., 20, his oldest son, who often joined him in pre-dawn prayer.

The climax of his transformation appears to have come in August, 1985, when Alvarez dozed off in a swivel chair while reading the Bible at home in Miami and, by his account, relived his life in a vivid dream.

“I woke up, and my mouth couldn’t stop confessing,” he said. “I got up, shut myself in my bedroom and kept crying, asking pardon for everything. From that moment, I have been at peace.”

Some who knew Alvarez and shared his beliefs say his conversion was so extreme that it clouded common sense. The family was troubled by his decision to return to Honduras, where he had thousands of enemies, and to travel unarmed through the countryside spreading the Gospel.

“He had such a strong personality that he could have achieved greatness, had he learned to keep things in perspective,” Leonel Solis, a childhood classmate, said.

The sign that Alvarez was awaiting to beckon him home came last April. It was a videotaped message from a Guatemalan minister who had visited Honduras. “God has your enemies under control,” the message said. “You can return, but stay out of politics.”

Alvarez’s older brothers, Arturo and Armando, warned him to stay in Miami. Honduras was in turmoil. The army was racked with tension over charges that some officers were involved in drug trafficking. Leftist students, abetted by the police, had rioted and burned a U.S. Embassy building to protest Matta’s illegal extradition to the United States on drug charges.

“The country may be falling to pieces, but if God wants me to go back, I will go,” Alvarez replied.

Soon, he became “Brother Alvarez” of the Interdenominational Missionary Church. With the minister, Gloria Ordonez, he devised a plan to join forces with other evangelical groups. The aim of the crusade was to convert 90% of this predominantly Roman Catholic nation within two years.

“He was going to conquer one province at a time,” explained Rene Gallo, a fellow missionary, sweeping his hand counterclockwise over a map of Honduras in the church’s tiny office.

Some critics of Alvarez were skeptical of his motives.

“He might have been trying to become the spiritual father for a new generation or trying to use religion to move back toward the center of political power,” said Joseph Eldridge, an American Methodist missionary who worked in Honduras for 2 1/2 years.

Gustavo Jr., who joined in the missionary work, insisted his father had no political ambitions and said:

“He always had a revolutionary impulse to change things for the better, but once he found Christ he rejected politics and took up a more powerful weapon--the Gospel. He had a clear vision: that Honduras would become the second Israel, that through belief in Christ it would prosper in all ways.”

Crowds formed wherever Alvarez gave his personal testimony and spoke of his vision. At each stop, there were usually a few converts.

One convert was Modesto Amador, Alvarez’s bodyguard and chauffeur for 15 years. Three months before his death, Alvarez persuaded Amador to give up his pistol. The two men carried Bibles as their only defense.

Friends in the army, worried by what they called a Cinchonero threat against Alvarez, repeatedly offered to provide free protection, his brothers said, but the answer was always no.

“The day I accept a bodyguard, I am doubting the Lord’s protection,” Armando Alvarez said his brother told him.

Alvarez’s assassins waited for his truck at a stop sign three blocks from his home. Alberto Abreu, a Miami native engaged to Alvarez’s older daughter, rode in the back seat and survived the attack. He told the family that the attackers shot out the tires, then sprayed the windshield with submachine-gun fire, wounding Alvarez and Amador.

Second Burst of Gunfire

Shot 18 times, Alvarez was apparently killed in a second burst of gunfire as he slumped protectively over his dying driver.

Meanwhile, there is evidence that the Cinchoneros indeed survived Alvarez’s “dirty war” and are making a comeback. In an interview in Nicaragua last August, a spokesman for the group, Alonso Martinez, told the Financial Times of London: “We are rebuilding. . . . Soon we will be ready to go on the offensive.”

But Ordonez, the minister who often traveled with Alvarez, said he told her weeks before his death, “Sister, the Cinchoneros don’t exist anymore.”

Many Hondurans who share that belief say that the Honduran army, which argues publicly that the Contras’ defeat could increase Sandinista-sponsored subversion here, may itself be fomenting some of the recent violence to jar the United States into increasing its military aid. Before his own death, Diaz, the drug dealer’s lawyer, told a reporter he was ready to testify that the army had killed Rugama, the Contra leader.

Other skeptics note that Alvarez’s public repentances skirted the issue of his own guilt in the “dirty war” and sought to blame others in the army. Two days before his death, he insisted in a radio interview that he had fought “within the law.” But he added: “When you send your people into the streets, what they do is their responsibility. How can you control them?”

“My brother was shocked by how much things had deteriorated since he left,” Arturo Alvarez said. “He thought Honduras was in a state of terror. The enemies of democracy, not just those on the left, were creating a climate of intimidation. He saw no political or military way out. The only way he saw was to change men’s hearts through God.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.