Study Is Said to Confirm Fears of Damage From Ozone ‘Hole’

- Share via

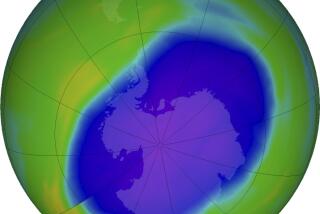

Results of new experiments conducted in the Antarctic last October during the austral spring appear to confirm fears that the large “hole” in the ozone layer caused by man-made chlorofluorocarbons may produce permanent damage to the fragile ecosystem, the National Science Foundation said in a statement to be released today.

The first accurate measurements of biologically damaging ultraviolet radiation at the Earth’s surface in Antarctica showed that levels were twice as high as is normal in the springtime.

Calculations based on the new measurements also suggested that levels of the damaging radiation were higher still--about five times normal--in October, 1987, when ozone depletion over the Antarctic was the greatest ever recorded, according to geophysicist John E. Frederick of the University of Chicago.

In a separate study also released by the foundation, oceanographer Osmund Helm-Hansen of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography found that photosynthetic activity of microscopic plants called phytoplankton was reduced by about 25% in the upper three feet of the Antarctic Ocean in October as a result of the increased radiation.

“Phytoplankton, by virtue of photosynthesis, furnish all the food materials which supply the needs of all the animals in the Antarctic Ocean,” Helm-Hansen said. “So if the rate of photosynthesis is significantly affected, it would affect the amount of food available for krill, fish, penguins and other animals.”

Ted DeLaca, head of polar programs at the National Science Foundation, called Helm-Hansen’s results “provocative,” but cautioned that the biological impact of ultraviolet radiation is very complex and will require a great deal of further study.

The two experiments are part of a continuing probe of the biological effects of increased ultraviolet radiation in the Antarctic sponsored by the foundation. Scientists hope the research will shed light on the eventual effects of increased ultraviolet radiation throughout the world caused by degradation of the ozone layer, which shields the Earth from most of the sun’s ultraviolet radiation.

Scientists believe that the Earth’s ozone layer has already been depleted by an average of about 2.3% worldwide, and some project that the depletion will exceed 10% early in the next century.

The Antarctic ozone hole, which covers an area the size of the United States, is caused by the accumulation of chlorofluorocarbons in polar stratospheric clouds during the long, dark Antarctic night. When the sun comes back above the horizon in October, it triggers a massive destruction of ozone by the chemicals.

The hole normally disappears in November or December, when it is dispersed by winds.

Normally, ultraviolet radiation in the Antarctic begins at a low level in spring and doubles in intensity in succeeding months, reaching a peak at the summer solstice when the sun’s rays shine most directly onto the Earth’s surface. Frederick and graduate student Dan Lubin found, however, that total ultraviolet radiation in 1988 reached the summer level almost immediately after the sun appeared in early October.

“It’s like the summertime radiation levels come early,” Frederick said. Based on their new measurements, he added, the researchers calculated that the spring radiation level in 1987 was about 2 1/2 times as large as the summer peak.

Helm-Hansen and his colleagues collected phytoplankton at different depths of the ocean, enclosed them in sealed bottles with radioactive carbon dioxide, and lowered the bottles on tethers to the depth at which they were collected. They recovered the bottles later and measured the amount of radioactive carbon dioxide taken up by the phytoplankton, a direct measure of their photosynthetic activity.

Some of the jars allowed all the sun’s radiation to reach the enclosed phytoplankton. Others blocked out all the damaging ultraviolet radiation, while permitting entry of the visible light necessary for photosynthesis.

They found that phytoplankton exposed to the ultraviolet radiation in the top three feet of the ocean carried out only 75% as much photosynthesis as those shielded from it by the jars. Photosynthesis occurred at near normal rates at greater depths because the water absorbed most of the ultraviolet radiation.

A decrease in photosynthetic rate means that the phytoplankton do not grow as rapidly as normal, so that fewer of them are present to serve as food for organisms higher in the food chain.

Both researchers will repeat their experiments in October, 1989, when the ozone hole, which seems to operate on a two-year cycle governed by weather conditions, is again expected to be severe.