New Lessons at Stanford

- Share via

Last week a bucolic corner of the Stanford University campus produced one rather commonplace lesson: Never throw anything away just because it is not absolutely up to date. From that, though, will flow cosmic lessons almost beyond the imagining of ordinary folk, let alone their comprehension. As Burton Richter, director of Stanford’s Linear Accelerator Center, puts it, what comes next will help scientists who are “trying to understand what’s in the mind of God.”

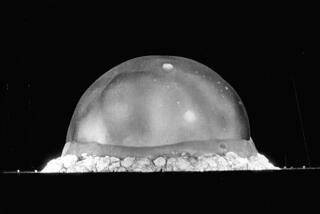

The something not quite up to date is the 20-year-old accelerator, which Richter and a team of scientists modified for $115 million--peanuts in the big-science business where people think in billions--by adding a loop to the end of an existing 2-mile-long tunnel through which sub-atomic particles ride waves of electric power. The accelerator now sends positrons into the loop in one direction and electrons in the other so that they collide at nearly the speed of light. The nuclear debris from what used to be called atom-smashing is scattered into a big concrete pillbox packed with instruments that sort out and identify the bits and pieces.

The cosmic aspect stems from the fact that after two anxious years of trying to calibrate the modified atom-smasher, Stanford’s instruments detected a Z particle in the debris Wednesday.

The Z particle is what Richter and his colleagues had been looking for. With the tricky business of calibration apparently solved, according to spokesman Michael Riordan, Stanford may become the world’s largest supplier of Z particles by the end of summer.

What makes the Z particles important to physicists is that they existed naturally for about one-trillionth of a second after the Big Bang that scientific theory says created the universe, and then they decayed. By creating Zs in a collider and observing the artificial particles decay, physicists can add one more level to what they know about how and why our galaxy and other galaxies arranged themselves as they did.

It also is a crucial step toward what Sidney Drell, co-director of the accelerator center, calls the Holy Grail of physics, a grand unifying theory that would explain the relationship between gravity and electromagnetism.

Stanford’s Z is not the first ever trapped in an atom-smasher. The first was detected six years ago in the collider of the European Center for Nuclear Research near Geneva by a team of researchers who were awarded the Nobel prize for physics for their effort.

But Stanford may become the first mass producer of the heaviest sub-atomic particle now known to exist, the one that may hold the key to understanding how, in a trillionth of a second, the pattern was set for everything that exists billions of years later. It is good to see California again on the cutting edge of science. But the real cause for celebration is one more lesson wrung from science, one more lesson that compels us to ponder once more the wonders of physical discovery, discovery with the power to make the mind both wince and dance.