Book Review : U.S. History as Progression of Corporate Technology

- Share via

American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm 1870-1970 by Thomas P. Hughes (Viking: $24.95; 349 pages)

The central thesis of Thomas P. Hughes’ “American Genesis” is simple and compelling. The most distinctive, impressive and important achievement in American history is not our political system, he says, but our technology.

We are a nation of builders. We have created modern technology and the culture that supports it. “Inventors, industrial scientists, engineers, and system builders have been the makers of modern America,” Hughes writes. “The values of order, system, and control that they embedded in machines, devices, processes, and systems have become the values of modern technological culture.”

Hughes argues that the modern world is the product of a hundred years of invention from 1870 to 1970. It was started by a stellar group of independent inventors--Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, Lee De Forest and Orville and Wilbur Wright, among others--who inexplicably emerged in the same place and at the same moment in history.

In short order, these rugged individuals gave way to scientists at research laboratories sponsored by General Electric, AT&T; and other industrial giants. It was a subtle but important change. Big companies tend to favor conformity over originality, improvements in existing products over boldly innovative new ones.

Research Organizations

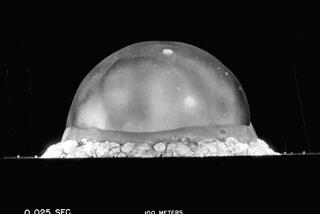

The next stage saw the development of system builders, people like Henry Ford and Frederick W. Taylor, the creator of scientific management, who organized technologies into units of control. Electric power grids resulted, Hughes notes, and so, ultimately, did the Manhattan Project, which created the atomic bomb.

“America’s creating, building, and systematizing genius reached its zenith in a nuclear enterprise, or technological system, that was a culmination of almost a century of ever-expanding invention, industrial research, and system building that extended from Pearl Street, Edison’s first lighting station in New York, to . . . Los Alamos.”

No one can gainsay the material benefits that the century of invention has bestowed on us. But there was a less-obvious Faustian bargain in the process.

The early shift from independent inventor to industrial scientist presaged the loss of individuality that order, organization and control would eventually impose on everyone. Most of us today are cogs in the great economic machine.

Japanese Implications

Hughes doesn’t say it, but he might have noted that Japan’s ability to beat us at our own game stems in large measure from the greater willingness of Japanese people to be those cogs.

In the 1960s, writers like Lewis Mumford and Jacques Ellul began to call attention to the downside of progress.

“Instead of seeing and sentimentalizing the United States as essentially a nation of democratic politics and free-enterprise economics, the writers and philosophers of a counterculture probed the depth and extent of the mechanization and systematization of America,” Hughes writes.

“They asked what problems arose from the man-made characteristics of built America, from--as Frederick W. Taylor said--no longer putting man first, but putting the system first.”

Hughes, a historian of science at the University of Pennsylvania, writes with sweep and detail. He links diverse phenomena like the military-industrial complex and modern art and architecture with his overall vision that order and control were the inevitable result of technological progress. His is an epic tale told with a rhythm and cadence that match it.

The subtheme of the individual versus the world recurs throughout the story. Though it was individuals who kicked off the century of invention, they were quickly supplanted by company men, who have remained in the driver’s seat ever since.

Death of an Inventor

Particularly poignant is Hughes’ retelling of the life of Edwin Armstrong, the visionary engineer who invented FM radio, only to be fought by RCA and other entrenched interests, who did not want their substantial investment in AM radio disturbed. After years of legal battles, Armstrong died a suicide in 1954. Hughes takes his story as symbolic of the era.

But in the end, he does not abandon hope for a change of direction that will bring new values to the fore while retaining the benefits that mass technology has bestowed.

Hughes recognizes that the current system and the forces behind it have tremendous momentum going for them. But, he insists, “Technology can be created and can be deployed that would heighten the quality of life, not simply the quantity of goods.”

Maybe so. But Hughes’ haunting book makes a better case for the problem than it does for the solution.