NEWS ANALYSIS : Rigid Regime Paved Way for National Chaos

- Share via

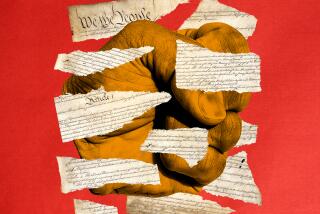

WASHINGTON — China’s sudden plunge into turmoil, with the government retreating into impotence and a divided army arrayed as if to wage civil war, has left stunned observers grappling for an explanation: How could the order of a powerful nation turn so quickly to chaos?

Paradoxically, experienced China analysts say, it was China’s very rigidity of leadership--the virtually unlimited authority wielded by its leaders, and their willingness to use it--that led to today’s slide toward anarchy.

What gave the appearance of command and control at China’s helm, they say, was in fact an inflexibility so brittle that, when the leadership was confronted with pent-up opposition, it apparently snapped.

Analysts readily agree that they did not foresee what would happen in China, and now they are groping for reasons for the startling turn of events.

From all appearances, “it was the rapidity of change together with the inability to compromise that produced this resort to violence,” said John K. Fairbank, a history professor at Harvard University.

A one-party system of Communist rule that by nature made change difficult contributed to the eventual rupture, U.S. experts say. But, they argue, the reasons for the government’s striking fragility may have less to do with communism than with the now-aged men who brought that ideology to power more than 40 years ago and have clung doggedly to power ever since.

Provoking the rupture were pro-democracy protesters whose appetite for change was fueled by unhappy memories of the tumultuous Cultural Revolution and the struggle of recent economic reforms.

Those students and workers, analysts note, are products of a society that is respectful toward well-exercised autocracy but mutinous toward leaders who violate their trust.

‘Mandate of Heaven’

The Confucians called that concept a “mandate of heaven;” and references to it could be seen until a few days ago on the banners across Tian An Men Square. But the government’s claim to that moral authority was lost when it answered the pleas for change with tanks and bullets.

What is left now is an astounding void, what analysts call a “crisis of confidence” so profound that many express doubts that the shattered authority might ever be made whole.

“The damage done to confidence in the system is going to take many years to undo,” says China scholar Harry Harding. “The legitimacy not only of the current leadership but of the entire political system in China is at stake.”

The fact that turmoil has been unloosed in China, of all places, still appears particularly remarkable, experts acknowledge. Here was an authoritarian government uncontested by formal opposition, ruling over a society that has been governed by autocracy for 2,000 years.

Chaos in the Past

At times in the past, chaos had overwhelmed China’s entrenched leadership. In the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976, 14-year-old Red Guards chased out party officials four times their age.

But that decade of near-anarchy was wrought by Mao Tse-tung and his confederates, who exhorted the youthful cadres. What is now unfolding in Beijing, experts note, is the product of the Communist regime’s first taste of the kind of turmoil that bubbles up from the bottom of the political order.

Eerie scenes from the Chinese capital symbolize the extent to which normal life has now been eclipsed, as wary cyclists pedal past bloodstains and smoldering tanks. Still-stunned experts, however, emphasize that what has befallen China in recent days was by no means inevitable.

The mass student demonstrations in mid-April might easily have been damped through minor concessions, they said. What propelled it into a standoff and ultimately a bloody clash, they argue, was an extraordinary cycle of intractability that let tensions escalate out of control.

“The crisis got more and more vicious as the days passed,” said China scholar Anthony Kane of the New York-based Asia Society. “Ultimately, the leadership really just cracked.”

Under other circumstances, the necessary concessions should have been possible. But in the one-party system overseen by the elderly leaders, no institutionalized opposition waits in the wings to respond to the public will. Power struggles within the party remain far removed from popular aspirations.

“There aren’t any democratic processes and the government categorically refused to consider them,” said June Teufel Dreyer, a professor at the University of Miami. “But the population has nevertheless decided it has a role to play.”

“There is absolutely no alternative to the Communist Party at this point,” added Harding, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “The choice that people face is to try to work to reform the Chinese Communist Party, or to fall into chaos because there is no alternative.”

Changes Since Mao

That stark dilemma is often overlooked, analysts said, by those who expect too much from the changes in China brought about since the death of Mao. In that 12-year period, mechanisms for succession have been debated and modern legal codes established.

And yet, the experts emphasized, China remains a society governed by a first generation of revolutionaries. Having turned China on its head, they remain reluctant to turn control to a new generation. After clinging to power for 40 years, they grow progressively out of touch. The phenomenon is not new in China. Through two millennia of imperial dynasties, notes Harvard’s Fairbank, “Emperors were for life.” And in their dotage, he noted, “They often became a little backward and corrupt and interested mainly in holding on to power.”

Thus does the 84-year-old Deng Xiaoping, officially retired and believed to be seriously ill, continue to preside over China’s future.

In China today, said Thomas Bernstein of Columbia University, there remains “the fear of surrendering the power to younger people, who leaders fear might do things that are threatening to their basic values.”

The result, Bernstein added, is the “inability of a man like Deng Xiaoping to release the reins of power as long as he’s alive.”

To be sure, the political and legal mechanisms established since Mao’s death mark a notable advance over what preceded it.

And yet, scholars note, such institutions were always alien to Chinese culture, and were never fully installed.

Instead of rule of law, said Stanley Lubman, an American expert on the Chinese legal system, “There has always been an emphasis on rule by just and virtuous men.”

Under the weight of recent adversity, China’s leaders have bothered little with the trappings of order, analysts point out. Hopeful speculation that the National People’s Congress might intercede to halt the hard-liners quickly dissolved. Even the powerful Central Committee might as well not exist. The White House conceded this week that it did not know who is running China.

“What we have seen in recent weeks is Deng’s conviction that it is his right and his ability still to override those institutions when he saw fit,” said Harding of the Bookings Institution.

Need Legal Restraints

If political institutions are to maintain order, said Columbia’s Bernstein, there must be “a willingness to be bound by some system of legal restraint. That just hasn’t happened.”

What this has produced, experts say, is a Chinese leadership determined to forge ahead but extraordinarily disconnected from the society it seeks to mobilize.

Yet that alone does not explain how the leaders’ rigid grasp on order was loosened.

“As long as there’s a reasonable degree of respect for the system--which comes from a combination of the instruments of power that the ruler has and some degree of satisfaction with the way in which the people are ruling, then power can be maintained,” said Clough, who teaches at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington.

“You can’t get around the fact that nobody expected the system to shatter the way it has,” said the Asia Society’s Kane. The explanation, he said, “is not just the instability of institutions, but the power of violence that lies beneath it.”

Party Provides Ideology

For 40 years the Communist Party provided the ideology that held the society together, providing the glue that bound citizens and their far-removed leaders. But events of recent decades wrought the kind of popular discontent that has simmered ever since, making the government appear ever more oppressive and weakening its hold, the experts said.

The seeds of discontent, Clough noted, date back to the trauma of the Cultural Revolution which “so damaged the party’s prestige in the eyes of the public that it never regained the kind of respect that it had.”

The growth of personal fortunes achieved through the vast economic reforms since then temporarily obscured some of the antipathy the Chinese felt toward the party. But those reforms more recently have bolstered the anti-government feeling, contributing to the hostility so vocally proclaimed by the marchers in Tian An Men Square.

One focus of discontent was inflation, crippling to those who rely on fixed government salaries and the cause of growing resentment. Another was corruption by officials believed to have profited from reform.

Those and other grievances were in many cases individual, lumped in a curious jumble with the pro-democracy aspirations voiced by students and intellectuals. But together they merged this spring in an amorphous but powerful coalition that exploded in anger as the leaders turned a deaf ear to it.

“The common denominator,” argued Brookings’ Harding, “would appear to be a loss of confidence in the ability of the Chinese government to deal effectively with the various problems facing the nation, to purge itself of corruption, and to give the impression of being responsive to the concerns of its citizens.”

Said Clough, “The mass of the people now have little respect either for the Communist Party or for communism as an ideology, so the only thing to hold the thing together is power.”

With that power now being mustered--by armies in Beijing arrayed against citizens and one another--and the next moves far from clear, China analysts would project only continued turmoil in China in the days and months ahead.

Over 2,000 years of imperial history, noted Fairbank of Harvard, each of China’s great dynasties was overturned after citizens were finally conscripted in great armies and joined battle in a great civil war.

“Every new regime comes in through power and fighting,” Fairbank said. “There’s a possibility now that they are beginning that process over again.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.