Johnson Admits Using Steroids, Blames Coach

- Share via

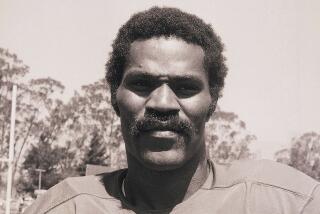

TORONTO — Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson admitted publicly for the first time Monday that he used anabolic steroids and other performance-enhancing substances, beginning in the early 1980s, and that he was aware the drugs are banned by international sports federations. But he attempted to shift the blame to his coach of 11 years, Charlie Francis.

“I’m not the coach,” Johnson said. “I just took orders.”

On his first day of testimony before the Canadian government’s commission of inquiry into drug use by athletes, Johnson, 27, also said that he would not have used steroids if Francis or Dr. Jamie Astaphan, who supervised the sprinter’s drug program for four years between the 1984 and 1988 Summer Olympics, had warned him of the potential side effects.

“Nobody took the time out to tell me what the side effects were,” he said. “They were happy making money and stuff.”

In Johnson’s only previous public statement on the subject, he said at a news conference here last Oct. 4 that he “never, ever knowingly used illegal drugs.” That was two weeks after he had tested positive for a steroid at the Seoul Olympics and was forced to forfeit the gold medal and the world record of 9.79 seconds that had resulted from his victory in the 100 meters.

Through the first 56 days of testimony at the inquiry, which was commissioned by the Canadian government’s sports ministry less than a week after Johnson tested positive, there was curiosity about whether the sprinter would stand by his original statement when called to testify under oath.

To do so would have contradicted previous testimony by Francis, Astaphan and several of Johnson’s teammates, who said they believed he knew he had used steroids and was aware of the potential consequences.

It might also have jeopardized his future in track and field if the inquiry’s commissioner, Ontario associate chief justice Charles L. Dubin, had chosen to believe the other witnesses.

Canadian Ban

According to the rules of the International Amateur Athletic Federation, which governs track and field, Johnson can return to competition when his two-year suspension ends on Sept. 24, 1990. But Canada’s sports minister, Jean Charest, has banned him for life from representing the country in major international competition such as the Olympics and the World Championships.

Charest, however, said he would reconsider depending on Dubin’s recommendation, which is expected to be in a report due after the inquiry ends late this year. The commission is investigating other sports besides track and field to determine whether pressure put on Canadian athletes by the government’s funding program has driven them to use drugs.

There were 39 witnesses before Johnson, but his testimony was by far the most anticipated. About 200 reporters, most of them from Canada and the United States but some also from Britain, France and the Netherlands, awaited Johnson on Monday outside the downtown office building that was rented for the hearings. He arrived with an entourage of friends and family in a gray van with tinted windows.

Although he has not worked out regularly since the Olympics, he appeared fit. Wearing a dark gray pinstripe suit and a black tie, he would not have looked out of place among the dozen or so attorneys who are representing the various clients at the inquiry.

Armstrong’s Questions

The only one who asked Johnson questions Monday was the commission’s co-counsel, Robert P. Armstrong. The others, including attorneys for Francis and Astaphan and Johnson’s own attorney, will have their turns before the end of the week.

There were concerns about Johnson’s ability to answer for himself. Although some people close to him have testified that he is neither as naive nor unwitting as his attorney has tried to portray him, Johnson, who came here from Jamaica when he was 14, has an accent and a speech impediment that often makes it difficult for others to understand him.

But there was no such problem Monday. Although he seemed unable to recall certain details and sometimes contradicted himself on minor points, he appeared relaxed and confident and displayed a keen sense of humor.

Speaking of Francis’ squeamish, fumbling attempt to inject him with a male hormone, testosterone, in 1985, Johnson laughed and said: “He was all shaky and stuff. I said, ‘Not any more. You’re not giving me any shots.’ ”

Johnson said that he began working out with Francis’ suburban track club in 1977 and recalled that the coach introduced steroids to him in 1982 or 1983. But he agreed with Armstrong’s suggestion that it could have been 1981, which is the year that Francis testified he first put Johnson on a drug program. Earlier that year, Johnson had shown his promise as a sprinter by finishing second in the 100 meters at the Canadian national championships.

“He said, ‘The whole world is taking these drugs,’ and the only way I’m going to be better is to take these drugs,” Johnson said.

He said he made no decision at the time but decided later that year to follow Francis’ advice.

“Charlie was my coach,” he said. “If he would give me something to take, I’d take them. That’s the way it’s supposed to be.”

Even though he said that Francis did not tell him anything about the drugs, including their names, he said he suspected they were banned because the coach hid them from the other athletes at the track when he gave them to Johnson.

He said his suspicions were confirmed in the 1983 Pan American Games at Caracas, Venezuela, where conversations with other athletes convinced him that he had been given steroids by Francis.

Asked if he realized at that time that he would be disqualified if he tested positive for a steroid, Johnson said that he had.

But he said that neither Francis nor any of the other athletes in the club ever discussed the potential side effects of steroids. Medical evidence was introduced earlier by Johnson’s attorney indicating that the sprinter had an elevated live enzyme count in 1988.

“If they had told me all the side effects, I wouldn’t have been part of the group at all,” he said.

A few months before Johnson finished third in the 100 meters at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, he said Francis introduced him to Astaphan. By the end of the year, Johnson said Astaphan had taken over the administration of his drug program. Even though Astaphan returned to his native Caribbean island of St. Kitts in 1986, he continued to treat Johnson through the 1988 Summer Olympics.

Astaphan testified two weeks ago that he informed Johnson of the potential side effects of steroids and that the sprinter asked him if the drugs could cause damage to his liver, kidneys or heart.

Asked by Armstrong if that were true, Johnson snapped, “I’m not a doctor, no.”

Johnson said he would have disassociated himself from Astaphan if the doctor had warned about the side effects.

“I would not longer have been involved in any relationship at all,” he said.

“You wouldn’t have taken drugs?” Armstrong asked.

“No,” Johnson said.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.