Overboard Over Games : Reasons Why They Thrill May Vary, but New Bumper Crop Shows Enthusiasm Unflagging for Board Games

- Share via

Quick, for 10 points, why do otherwise stable, morally upright, Nintendo-hating citizens stay home and play board games?

(A) Some new games are so realistic in simulating business world power rituals that you think you’re actually getting practice--without having to suffer public humiliation when you fail.

(B) Cocooning is fashionable and playing silliness-producing games such as Pictionary and Outburst proves you can have fun stuck at home with the ones you love.

(C) You might learn something. Consider this tiddlywink from Trivial Pursuit: “What CIA director’s telephone mouthpiece had to be cleaned daily because of his incessant tie-chewing and drooling?” Answer: “William Casey’s.”

(D) All of the above, depending on whom you ask.

The correct answer is, of course, all of the above, and far more. Everybody’s got an opinion on a topic as familiar as board games. But--bonus question time--why are people often so vehement on the subject? Why do so many people seem to either love board games or loathe them? As you might expect, it goes right back to your childhood--prime game-playing time. “Everyone’s first exposure to board games is as a child,” explains Century City-based psychologist/attorney Rex Beaber. “That exposure will often taint their experience of the game. Among childhood players, there’s always the Monopoly champ, the Scrabble champ.

“People tend to like what they’re good at. . . . Those people, who in childhood were game winners, tended to like games and often choose to continue at them.”

But even the losers may later become game enthusiasts, says Beaber. One-time flunkees can “now be winners, they can kind of have a corrective experience as adults. They no longer have to be the person who could never find the word in Scrabble. . . . They’ve gone to college now.”

A Yearning Fulfilled

Beaber reasons, further, that those who love staying home and playing games may be yearning for the slow, community-influenced, agrarian style of life popular in the early part of the century, before it became customary to seek entertainment outside the home.

As for those who dislike games or play them only under protest, Beaber thinks life style considerations may be a factor. Indoor activities such as board games “tend to be more attractive to people who are more sedentary in their approach to recreation,” he says. “People who go out and play basketball on the weekends by and large are not going to be Monopoly players.”

Nor are extremely competitive individuals, in the view of Angelo Longo, a psychotherapist who works as director of research and development for the Games Gang, which markets Pictionary, the board game Toy & Hobby World magazine has ranked as the best seller in the United States for the last two years.

‘More Competitive’

“Psychologists have found that people who don’t play games are often more competitive (than those who do),” Longo says. “They really don’t get in a situation where they might lose. A truly competitive person will only wait until the odds are strongly in their favor to play.”

Or perhaps only play games where winning and losing is no big deal. Many observers note that the genre of socially interactive games pioneered by Trivial Pursuit in the early ‘80s and carried on by Pictionary and others downplays the competitive element. Such games have attracted big audiences, including lots of adults who once hated board games.

Indeed, trend-setting Trivial Pursuit was invented by a man who claims to hate board games.

It’s No. 3

“I don’t play games. I shoot pool, play golf,” Toronto-based Chris Haney insists, adding that Trivial Pursuit is now the third best-selling board game of all time, behind Monopoly and Scrabble.

Even now, Haney holds the distinction of never having played Trivial Pursuit. Why not? “I know all the answers,” the former picture editor of the Montreal Gazette laughs. “Trivial Pursuit is really not a game, if you know what I mean.”

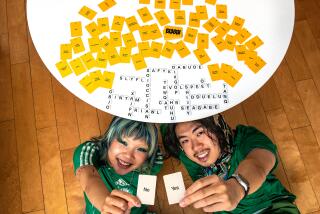

Longo surely does. He points out that the non-game games of the ‘80s--whose popularity is expected to continue into the ‘90s--all basically demolish the concept of winners and losers. “The process of people getting up and drawing and making fools of themselves (playing Pictionary) is a lot more interesting than the outcome,” Longo says. “You don’t recall whether you won or lost, you recall what people drew.”